The education select committee held their first session yesterday with what it called a “discussion around the complexity of the levy, its impact on smaller businesses (non-levy payers) and the use of the levy to fund higher level apprenticeships”.

You can watch the session here.

As one of the witnesses, I prepared some analysis and notes ahead of the session. In the spirit of sharing is caring, I’m publishing them here in the hope they may be useful.

Q1. How did the introduction of the apprenticeship levy in 2017 affect employers in different industries?

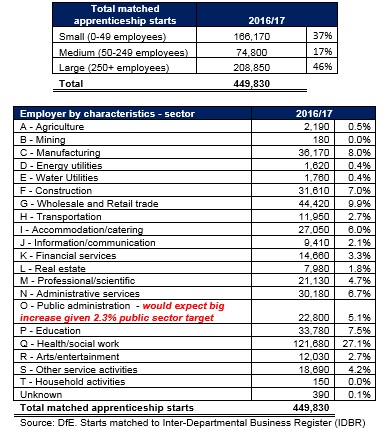

An excellent question that is very difficult to answer (anecdotal evidence is of little to no value) in the absence of data on apprentice industry characteristics since May 2017. The DfE did publish “experimental” data on “apprenticeships in England by industry sector” (click here) in October 2018, but this only goes up to 2016/17, before the levy was introduced. The DfE said they planned to publish more up-to-date data in October 2019, but delayed this “to enable analysis looking at the impact of the introduction of the apprenticeship levy on employers engaging with apprenticeships, as well as including data from the 2018 to 2019 academic year”. The DfE will now publish this data at 09:30 tomorrow (12 March 2019).

Here’s the data from 2016/17, and with the 2.3 per cent public sector starts target, I would expect to see significant growth in that sector.

More generally, I can say as an analyst of apprenticeships data for more than a decade, the level of transparency since the introduction of the levy has significantly fallen. Beyond starts and achievements, there is now very little financial data published at all in terms of provider or employer funding. This is something the committee may wish to challenge both the Treasury and DfE on – as it makes impact and policy assessments very difficult.

Q2. Why was there a large fall in apprenticeship starts after the introduction of the levy?

It is important to understand that the £2 billion+ levy tax income was just replacing £1.5 billion the Treasury was putting in – so it was not the introduction of the levy that caused a fall in starts.

The very predictable fall is starts was actually caused (mainly) by six changes the Education and Skills Funding Agency made relating to funding rates, rules and provider registers that came in at same time as levy in May 2017.

We know this was predicted as there was a rush in starts before these changes were applied from May 2017. There were 134,000 starts in March/April 2017 (two months before the changes) compared to 79,000 the year before, which in May/June 2019 (two months after the changes) dropped to 27,000 (74,000 the year before).

The six changes that meant a drop in starts was very predictable:

- Framework rate changes. From 1 May starts on all frameworks switched from a sophisticated formula to a very low ‘cap’ rate, such as £2,000 for business admin, reported by FE Week at the time. Some late changes were made to include some disadvantage funding and an uplift for 16/18s (who were particularly hit by switching to a single cap) – but still much lower rates than before, and rates for standards often more than double. Providers were telling FE Week that many of these made their programmes unviable – so they stopped delivering starts.

- Mandatory fee for first time. From 1 May employers had to either pay 10 per cent (now 5 per cent) or use their levy funding (if they had any), even for 16-18s. Before then, many paid nothing at all (despite the fact the government had a 50 per cent assumed fee for those aged 19 and over). Clearly many walked away when they had to pay. The annual cost of halving the co-investment to 5 per cent is £60 to 70 million annually, according to the Treasury. This is probably one of biggest factors in the fall in starts.

- Subcontracting tightened up. From 1 May starts, under a new rule, all main providers (such as colleges) had to deliver a significant number of apprenticeships to the employer alongside the subcontractor. FE Week estimates this cut subcontracting in half to about £150 million.

- Wave 1 applications to register of apprenticeship providers. Many providers, such as colleges in Birmingham, were initially hampered by not getting on the register early on.

- Botched non-levy tender with £200,000 minimum. First attempted scrapped. Second attempt was announced in December 2017 for contracts from January 2018 (so late) and some big successful providers, like Exeter College, failed to win a contract at all. The £200,000 minimum stopped many (such as universities) from being allocated anything as the ESFA reduced bids by as much as 67 per cent (in London). North East Employment & Training Agency Ltd, a provider which has been running for 30 years and is rated ‘good’ by Ofsted, bid for just over £300,000, a tender which was “realistic based on our current levels of delivery”, according to its managing director Stephen Briganti. He told FE Week his tender was successful but the pro-rata awarding process saw any potential award fall below the £200,000 minimum requirement and the “end result of this is that we are being offered nothing”.

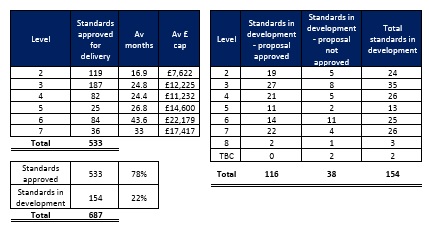

- Switch from frameworks to standards. From high volume, shorter and lower funding value frameworks to low volume, longer and high value standards – hence average funding for starts more than double forecast, according to a National Audit Office report. But standards were initially slow to come on stream. A total of 533 standards are now approved for delivery with another 154 in development.

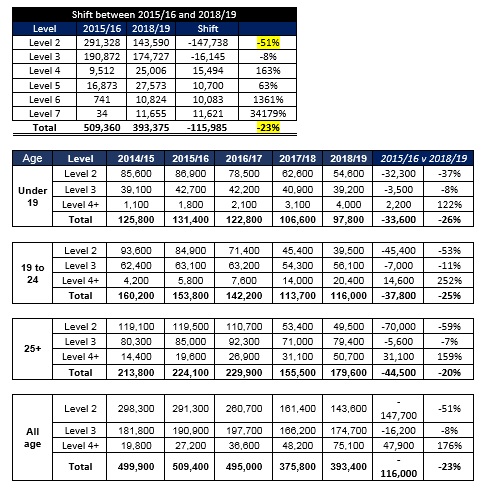

Since then, starts have not fully recovered (23 per cent down), particularly at level 2 (for all age groups) which is 51 per cent down on the year before the levy was introduced. In terms of a priority area, the number of 16-18 starts remains 26 per cent down. The growth at level 4 and above has been driven by… a) the introduction of standards at that level and… b) a new and very significant rule from May 2017 that people with degrees (no limit on level of prior attainment) can be funded for apprenticeships.

Q3. How have the government’s recent reforms, such as the increased flexibility for levy-payers to be able to transfer up to 25 per cent of their funds, affected employers?

The policy to allow levy-paying employers to transfer up to 10 per cent per year was introduced a year into the levy to help large employers spend their funds and support smaller employers. With less than 0.5 per cent used this way, Anne Milton questioned at the Conservative Party conference in October 2018 if it was “too small to make it worthwhile”.

Take-up remains slow despite increasing the transfer maximum to 25 per cent in April 2019. DfE figures from February 2020 show that just 870 (0.5 per cent ) starts were funded via levy transfer out of 162,000 levy-supported standards for 2018/19. However, the DfE also report uptake has increased to 1,500 starts funded via a transfer in recent months.

The challenge is that it is a high administrative burden for the levy-paying employer because funds can only be transferred once an apprentice has been enrolled and the risk remains with the levy-paying employer. The ESFA is, however, aware of the risk to public funds (fraud) with this type of transfer ‘market’. Anne Milton said at a fringe event in October 2018: “We have to have rules, and they’re irritating and bureaucratic, but fraud has been an issue.”

The West Midlands Combined Authority has big businesses investing in an “apprenticeship levy transfer fund”, which they hope will collect up to £40 million. This was part of a “£69 million skills deal agreed with the government in summer 2018 – the first of its kind in the country”. It “means the large employers donate a portion of their unspent apprenticeship levy funds to the smaller companies, covering 100 per cent of their apprenticeship training and assessment costs”.

Q4. What changes could be made to the levy to ensure it is easier for businesses to upskill their workforce?

Some thoughts, on basis the Treasury (despite making a £1.5 billion saving per year by replacing apprenticeship spending by the levy) won’t pump extra money in nor see it as politically possible to lower the £3 million threshold, nor increase the 0.5 per cent levy rate:

- The money is not there to widen what it can pay for. In fact, right now “hard choices” need to be made to stop paying for everything at on average double the forecast rates (see the NAO report from last year and evidence from the DfE’s permanent secretary to the education select committee). Start with being honest that it is public money and it can’t pay for everything. Failure to do that will clearly result in a big row when inevitable restrictions kick in. Would providers prefer prioritising funds or the Institute for Apprenticeships and Technical Education (IfATE) making rates for standards so low they are unviable?

- Prioritise the young (ring-fence the funds again – which was around £600 million before May 2017) and those entering the job market by fully-funding them, it was bonkers to charge employers for 16-18s, as I’m sure Professor Alison Wolf, now in Number 10 policy Unit, would agree. Employers should pay a significant contribution for existing employees, and should pay for all 25+ existing employees without subsidy. Many of the training programmes for existing employees should either be paid for by the Office for Students via a loan, or via alternative routes (such as the planned National Skills Fund).

- Give employers a better product and more confidence in the providers by improving the quality assurance oversight – starting with Ofsted taking on all the level 6+ provision and Ofqual taking on the full external quality assurance role.

- Give back apprenticeship funding rate responsibility to the ESFA and scrap concept of the negotiated rate – that has failed (nearly all providers charging 100 per cent and they are confused by funding rule requirements to reflect prior learning and experience in the price). IfATE represents employers so how can they be best placed for setting rates for the use of public money – how is that independent?

- General financial and quality oversight and clarity of responsibilities between DfE, ESFA, IfATE, Ofsted, Ofqual, QAA and OfS is a mess and is letting apprentices down.

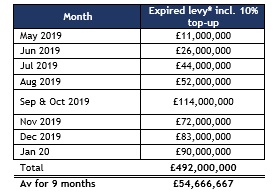

- Scrap the 10 per cent levy top-up (that’s around £200 million per year) and charge SMEs a lot more for existing employees. It is madness to be subsidising training for existing employees on £100,000+ that already have degrees by 95 per cent.

- Consider implications of reducing the 24 month sun-setting period on the levy (originally it was meant to be 18 months).

- Try not to change too much about the wiring as the system is bedding in.

Some other issues and analysis that may be of interest:

- Framework rates very, very low as we switch to expensive standards

- There are still 155 different frameworks still in use at different levels according to quarter one 2019/20 starts, making up 26 per cent of all starts

- But all frameworks will be switched off for new starts by 31 July 2019

- Framework caps set very low. E.g. the level 2 accounting framework has a cap of just £2,000 (plus £1,400 extra for 16-18s) with 474 starts, of which 237 (50 per cent) are 16-18 of which 199 (84 per cent) are at FE colleges. Yet the level 2 accounts / finance assistant standard has a cap of £6,000 (plus £1,000 extra for 16-18s) and had 76 starts in three months.

- The level 3 accounting framework has a £2,000 cap with just 117 starts in last 3 months. The level 3 assistant accountant standard has a cap of £8,000 with 1,747 starts in three months

- Level 3 business admin framework is set at £2,500 (plus £1,500 for 16-18s) and had 558 starts (239, 43 per cent, colleges). The level 3 business admin standard is £5,000 (plus £1,000 for 16-18s) with 3,735 starts (958, 26 per cent, colleges).

- As at today there are 533 available standards and a further 154 in official development (making a total of 687). See table below.

- Even many level 2 standards can have very high rates, like the carpentry and joinery programmes at £12,000 or the land-based service engineer at £15,000.

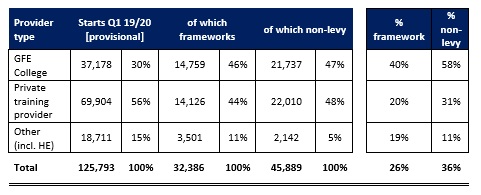

2. FE colleges look particularly vulnerable as they have delivered just 30 per cent of starts from August to October 2019, of which 40 per cent are still on the old frameworks and 58 per cent are with non-levy employers (SMEs).

3. Unspent funds shows policy is working (government planned for around 50 per cent), because if levy employers used it all there would be £0 for small employers, English and math, incentive payments etc.

For 2018-19 there was £1.7 billion of £2.3 billion levy spent, leaving £489 million underspend on apprenticeship budget (a budget that had been set in 2015). Non-levy funding was around £500 million (30 per cent) and levy paying employers spent around 30 per cent of what was in their account. FE Week reported in April 2019 that of the £489 million the Treasury took back “just over £300 million”. The £2.5 billion budget for 2019-20 and “final end-of-year out-turns will be published in the 2019-20 annual report and accounts”, says the DfE.

4. The DfE do not like talking about it, but it is clear funding is now running out as cheap frameworks are being replaced by the expensive standards

NAO report, March 2019: “The average cost of training an apprentice on a standard is around double what was expected, making it more likely that the programme will overspend in future”…“employers are developing and choosing more expensive standards at higher levels than was expected. The Department has calculated that the average cost of training an apprentice on a standard at the end of 2017-18 was around £9,000 – approximately double the cost allowed for when budgets were set.”

ESFA annual report, July 2019 : “Increased demand for apprenticeship funding in future years has the potential to place pressures on funding provided by the apprenticeship levy. Budget pressures will be explored through the Spending Review process.”

5. Current trends increasingly showing young people losing out

This is the DfE analysts’ description of the first quarter of this year: “Starts by under 19s have seen a fall of 11.2 per cent from 2018/19. In contrast, starts by those age 19 and over fell by just 1.3 per cent and there has been a small rise for those aged 25 and over of 1.2 per cent. Since 2017/18, starts by adults (19+) have grown by over a quarter (25.6 per cent), while those for under 19s have fallen by 12.8 per cent. The 25 and over group have seen an increase of 44.8 per cent over this period.”

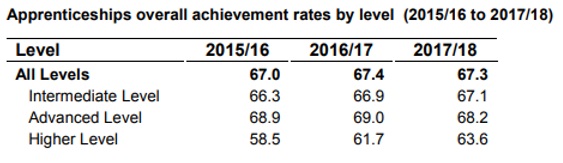

6. A third of apprentices fail to finish their course, and this is set to get even worse with frameworks moving to standards

Look out for the 2018/19 national achievement rate tables (NARTs), due for publication on 26 March. We’re expecting to see a massive 10 percentage point drop in achievement rates, which the DfE is very concerned about.

6. The controversial MBA apprenticeship is being reviewed after Gavin Williamson wrote to the IfATE to say: “I am committed to maintaining an employer-led system, but I’m not convinced the levy should be used to pay for staff, who are often already highly qualified and highly paid, to receive an MBA.

“I’d rather see funding helping to kick-start careers or level up skills and opportunities. That’s why I’ve asked for a review of the senior leader apprenticeship standard to ensure it is meeting its aims.”

There were close to 1,500 starts on this £18,000 standard in a single month (September 2019) – which could have paid for over 10,000 16-18 places.

But there are many other management standards that should also be reviewed through the lens of kick-starting careers, including the £22,000 level 6 chartered manager (645 starts in September), the level 5 manager (1,408 starts in September) and the level 3 team leader (2,290 starts in September).

Also, should many others at level 7 be publicly funded as apprenticeship – given some look like universities simply cashing-in? Such as the £9,000 university professor apprenticeship (academic professional).

The IfATE’s wesbite states that “115 universities and other higher education providers across the country are committed to recruiting academic professional apprentices” and the expected uptake of this programme is “approximately 2,000 new starters per annum”. So 2,000 starts x £9,000 = £18 million.

The IfATE’s website adds: “Academic professionals work within the higher education sector delivering higher education teaching and undertaking research to support the development of knowledge within their discipline”…“Employers will set their own entry requirements, which will usually be a postgraduate degree level (level 7) qualification in an area of disciplinary specialism.”

The end-point-assessment is simply a one-hour presentation.

Also, FE Week revealed in April 2019 that plans for PhD-level apprenticeships had been thrown into doubt after the IfATE raised concerns they were not in the “spirit” of the programme. But we understand it is back on track and in January 2020 the institute said: “The proposal for a level 8 clinical academic professional standard has been approved for development following consultation with the Department for Education.”

There are currently three Level 8 apprenticeships in development – which – it seems – is being pushed through by the DfE regardless of IfATE concerns.

I’ve hit 2,500 words, so that’s all for now!

Email me your thoughts: nick.linford@lsect.com

Your thoughts