The Education and Skills Funding Agency has paid a further quarter of a million pounds to a firm that had its training contracts terminated following an undercover FE Week investigation.

Talent Training, which was based in South Tyneside and claimed to have £130 million of apprenticeship levy business, was caught offering banned inducements in the summer of 2017.

Following this newspaper’s exposé, the ESFA cancelled the company’s skills contracts and it went into administration with around 100 staff being made redundant.

Members drawings by David Harper were in excess of the distributable reserves and he has agreed a six figure offer to pay in full by 30 June 2019

But it has since come to light that Talent Training’s administrators, David Rubin and Partners, claimed a huge chunk of public cash – £258,000 – following the demise of the provider, of which almost £30,000 was handed over to the private provider’s managing director, David Harper (pictured).

The company, which owes over £1 million to its creditors, has also launched a legal challenge against the ESFA in an effort to claim more cash.

An “administrator’s progress report”, published on Companies House on April 5, reveals that the £258,000 was paid for training that the company claims to have carried out, but was not paid for by the ESFA.

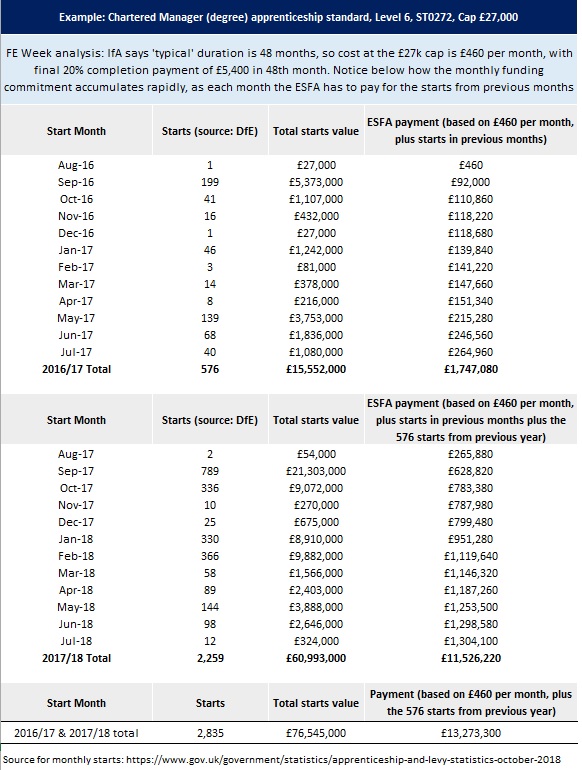

“The final apprenticeship and adult education data return was submitted in the sum of £195,214.53 and the ESFA approved the release of caps on the provider’s contract for period 2016/2017 amounting to £78,797. The total amount therefore due to the company was £273,011.53,” it said (click here to read full document).

“After the ESFA conducted their reconciliations of the account, the sum of £7,500 was deducted in respect of grants that had not been passed to employers and £8,368.38 was also deducted in respect of unpaid invoices as a result of independent audits completed in May 2017.

“In view of the above, the net payment received from the ESFA was £258,143.15.”

The administrators added that they will claim nearly £250,000 in fees.

“In accordance with these resolutions, we have drawn down fees of £205,236 plus VAT and I would confirm that my fees estimate for the administration remains unchanged,” the report said.

It added that Mr Harper, a millionaire businessman who has operated in the training market for years, was “instructed” to assist with the collection of the ESFA payment and other debtors monies outstanding to the company “on the basis that he had an in depth knowledge of the debts”.

The “agreed basis” of his fees was “10 per cent of debtor recoveries plus expenses capped at £4,000”, all of which were “incurred”.

“Therefore the sum of £29,814.31 has been paid to DH,” the report stated.

Additionally, £6,081.22 was paid to “three former employees” who assisted Mr Harper in “collating records and submission of the return to the ESFA”. None of these employees were named.

The document does however also show that Mr Harper owes the company up to £1 million, after taking out a director’s loan.

“Members drawings by David Harper were in excess of the distributable reserves and he has agreed a six figure offer to pay in full by 30 June 2019,” it said.

The document also reveals that Talent has opened a legal case against the ESFA for terminating its contracts and its administrators are pursuing more compensation as the company moves into liquidation.

It said the legal action has “a high potential recovery value”, and while the “claims are being robustly defended”, David Harper is “continuing to assist the joint administrators and WH [solicitors Ward Hadaway], and will continue to do so in the forthcoming liquidation”.

Talent has large creditors’ debts totalling more than £1.44 million, including over £150,000 owed to the HMRC, according to a document published on Companies House in September 2018.

In accordance with these resolutions, we have drawn down fees of £205,236 plus VAT

FE Week attempted to contact Mr Harper and David Rubin and Partners multiple times but neither responded to requests for comment.

The undercover FE Week investigation carried out in June last year caught a Talent employee offering as much as 20 per cent of its government funding per apprenticeship to a firm that was considering its training services.

The company insisted at the time that no inducement payments had actually been paid, but went into administration two months later when the ESFA pulled its contracts.

David Rubin and Partners is no stranger to working with Mr Harper.

Companies House shows the firm has handled the administration for a number of other companies that he was a director for.

These include hco-consult and Driving Careers Limited, which both went into voluntary liquidation in November 2017.