Providers will be asked to log apprentices’ off-the-job training hours to prove that the deeply unpopular minimum funding requirement is being met, the government has revealed.

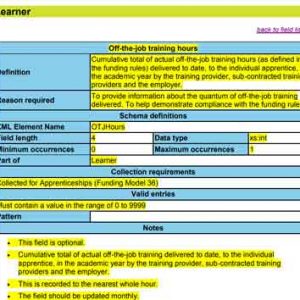

A new data field for individual learner records (ILR) – which is to be updated monthly – is supposed to “help” providers “demonstrate compliance” with the requirement for at least 20 per cent of apprentices’ time to be spent training away from work.

It will not be introduced until 2018/19 and is described in new ILR guidance as “optional”. But the Association of Employment and Learning Providers believes that it goes against previous assurances over how the rule, which is hated by employers, will be enforced.

“All along Education and Skills Funding Agency has assured us that there would be no additional administrative burdens, but this a significant add-on,” said AELP boss Mark Dawe.

“It’s another example of process being prioritised over outcome, imposing more bureaucracy on employers and providers, while offering no insight on the quality of the learning.”

Further guidance on the new field explains that it should record the “cumulative total of actual off-the-job training delivered to date, to the individual apprentice, in the academic year by the training provider”.

It should also take into account “subcontracted training providers and the employer”.

The data is to be recorded on a monthly basis to the “nearest whole hour”.

This will contribute to the full ILR for each learner, a data record that must be kept by providers and returned to the ESFA to secure funding.

The funding rule introduced last May requires that every apprentice “spend at least 20 per cent of their time on off-the-job training”.

It is a major bone of contention among employers, particularly smaller firms that claim they cannot afford to let apprentices spend a fifth of their time away from work.

This has had a knock-on effect for providers struggling to convince companies to take on apprentices, and provoked growing calls for much clearer explanation on how the rule will work in practice.

AELP, ahead of its autumn conference last November, at which the rule loomed large, asked the government to address employer resistance to the rule.

It is one of many actions that the association has been asking for, to foster a “more flexible” approach to the apprenticeship reforms and make them a success – and something that apprenticeships minister Anne Milton has herself said she would like to implement.

A DfE spokesperson explained why the new data field was being launched.

“This new field will provide insight for the DfE and the Institute for Apprenticeships into the amount of time apprentices on particular apprenticeship standards and frameworks spend on off-the-job training. The insight will help policy makers evaluate the effectiveness of apprenticeship reforms,” he said.