His name, and the name of his think tank, gets everywhere. How is one man who left teaching twice so influential in the busy world of education policy?

You have to admire Tom Richmond’s nerve.

There aren’t many teachers who, after three years in the classroom, decided the Department for Education was messing up, thought they’d offer to help out – and ended up doing precisely that, as a civil servant adviser to Michael Gove and then-skills minister Matt Hancock.

He may also be unique in returning to the classroom and finding, in his own words, that “Brexit was sucking the oxygen” out of education policy debates, and deciding to set up his own think tank instead.

Nowadays, Richmond and his think tank, EDSK (which stands for Education and Skills) are featured regularly across the press: his report on reforming assessment was covered across the i, the Mirror, the Express and trade media in January, while another on ‘fake apprenticeships’ hit BBC headlines last year.

Also unlike most think tanks, EDSK gives FE proper attention. Out of ten reports, its first was on Ofsted inspections in schools, but its second was on post-18 individual education budgets. There are two more, on the apprenticeship levy and the purpose of FE. That’s three reports: the same number EDSK has published on schools (the other reports are on higher education).

Yet for a policy obsessive, Richmond says “in the first 25 years of my life, I’d never shown the slightest interest in politics. Until I went into the classroom.”

He is the third of four children, born to a software developer father and a mother who retrained as a modern languages teacher to help pay for his fees at Haberdashers’ Aske’s private school.

Having “never really fallen for any subjects” at school, Richmond was at a loss what to study next, when he came across a “dusty old psychology textbook” in the library.

“I absolutely fell in love with the subject in the space of a single book,” he says. He studied psychology at Birmingham University, then decided to “dig into the practical side” of the subject and turned to teaching. He took a PGCE at the UCL Institute of Education, followed by a masters in child development, and volunteered for Childline. The initial goal was to “share the love of my subject”.

But this was soon overtaken by another preoccupation, in his first job teaching A-level students in 2004. “I started, like many teachers around the country, being the recipient of how things should work,” he begins. “And it dawned on me that some very strange decisions were being made.”

At the time, New Labour was seeking to switch from six to four A-level units. “I thought, there may be arguments for this, but the disruption it will cause me, compared to any real benefits to my students, is surely wrong. Who is advising these politicians?”

But is someone with only three years’ teaching experience well placed to advise ministers?

“It felt to me there were very few perspectives from teachers getting through.” At the time “there wasn’t really a crop of young teachers trying to make a difference using what they’d learnt” when he left his school in 2007, he says.

First, he became a research intern with Conservative MP Andrew Turner, then a researcher at the Social Market Foundation on reforming benefits.

His first job in education policy was at the Policy Exchange think tank from 2008 to 2009, under education policy expert Sam Freedman, who later also advised Gove. Policy Exchange is seen as right-wing leaning – given his work for Turner, is Richmond?

“I wasn’t strongly political. I’d been a member of a teaching union before,” he shrugs, before saying it was the coming change that appealed to him.

“It was healthy that a new government came in in 2010, and said ‘some things are not working, we’re not convinced by coursework, and attainment around the C/D borderline is a problem’.”

He adds: “Policy Exchange became an ideas-generating machine, and I found that very exciting.”

It was here that Richmond became a school teacher deeply interested in skills. Freedman was clear this was a “huge blind spot” in policymaking, partly because so few MPs, civil servants and policy advisors had experience of the FE and skills system, he adds.

Digging into apprenticeships and colleges has made a lasting impression on Richmond. “One of the things it rammed home to me was that we have these enormous cliff edges in our education system, and we have no concept, it seems, of making a smooth transition from the world of education to employment. I’ve never seen another country treat it like that. They work much harder to blend the world of education and employment, where employers are much more freely involved in the world of education.”

He raises his eyebrows. “We know the scarring effects. I find it immensely frustrating.”

After advising the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development, and being head of policy on the Welfare to Work programme for unemployed adults at G4S, Richmond soon found himself being interviewed by Hancock to advise the government on skills in 2013. (It perhaps says a lot that the government still looked to a former school teacher who had learnt about the skills system, rather than an FE member of staff, to be their skills adviser.)

He was kept busy. Both the Wolf Report on vocational education in 2011 and the Richard Review of apprenticeships in 2012 were a “sign” to Richmond that “the government realised there was a really important agenda that hadn’t been finalised”, he says. He worked on everything from reforming the apprenticeship system to helping with the introduction of traineeships and new vocational qualifications.

But after two years at the DfE, Richmond wanted to return to working with young people, and so joined a sixth- form college in 2016. It had been almost ten years since he’d been a teacher. How was it this time?

“I was working 60- or 70-hour weeks, which was strangely reminiscent of me being in teaching before,” he says. “I was not able to shave off any hours in the week, even though I knew the reforms were coming!”

The job was clearly not done. So in 2018 Richmond took a couple of research fellow posts: working on the apprenticeship levy for the Reform think tank, and writing a report on T Levels for Policy Exchange.

In that, he acknowledges the “entirely justified concerns” around timescale for T Levels, and calls for awarding organisations to join employers in consortium, in an attempt to head off delivery woes early.

Then in 2019, he founded EDSK. The output has been immense, with each report snappily titled and usually around 60 pages.

The Requires Improvement report on Ofsted calls for government to scrap the four overall grades and to introduce a ‘score card’ packed with information instead (you can imagine the suggestion being welcomed by colleges, but it focuses only on schools).

His second report, Free to Choose, also from 2019, calls for post-18 students to get a ‘learning account’ with up to £20,000 (depending on how disadvantaged the student is) to spend on a “single tertiary education system” of universities, colleges and apprenticeships. Again, you can hear colleges cheering.

The third report on FE hit the headlines in January 2020 for claiming that half of all apprenticeships started since 2017 were ‘fake’ and had been wrongly allocated £1.2 billion.

Richmond called for a new world-class definition of an apprenticeship decided by the DfE (not employers), and said the term ‘apprenticeship’ should apply only to level 3, not to levels 4 to 7, which should be called ‘technical and professional education’ instead.

“Bearing in mind other think tanks have had a 20-year head start, setting up a new think tank in this environment is a steep learning curve,” smiles Richmond. It’s funded through sponsored research, events and an annual ‘partnership’ scheme for supporters. You can see he’s pleased with how it’s turning out.

The success is likely down to a multitude of factors. First, Richmond can write exceptionally clearly, and makes bold recommendations aimed straight at the DfE – a win with journalists and policymakers alike.

Second, he can think around the stickiest of problems. Take the fourth report relevant to FE, Further Consideration, this time co-authored with another researcher, Andrew Bailey.

Although Bailey is, again, a former school teacher, the report was funded by the Further Education Trust for Leadership and included interviews with the great and good of FE.

The report makes the intriguing proposition that all FE colleges should be split into separate institutions with “their own brand and identity”: community colleges (for entry- level courses), sixth-form colleges (for A-levels), and technology colleges (for all technical, vocational and apprenticeship training, with a monopoly on T Levels).

It also called for an ‘FE director’ in every area. Even if you don’t agree, it’s a comprehensive effort to plan a more unified system, and well worth a read.

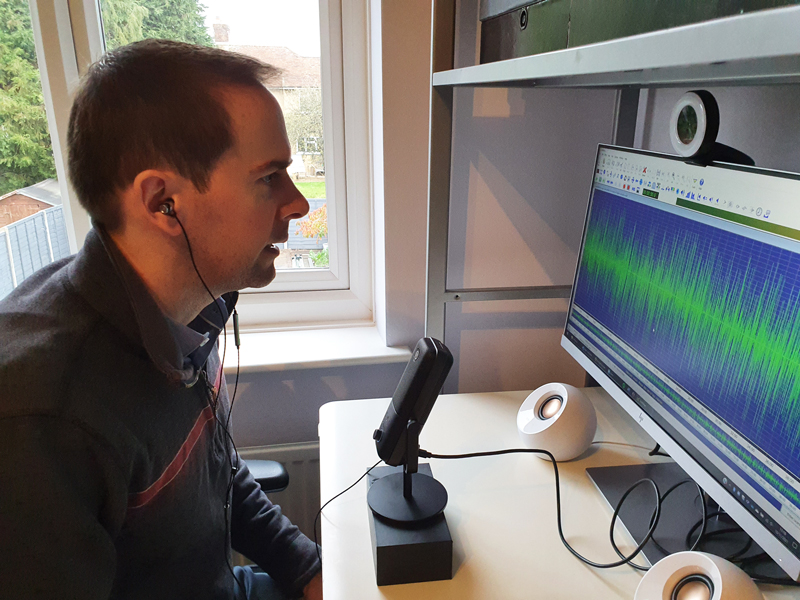

Finally, it definitely helps when journalists can say “a former Michael Gove advisor says”. Now he’s even set up a new podcast to discuss the issues of the day. Taken together, these factors have made Richmond an unusually powerful former teacher.

Yet the fact remains he was pushed out of the classroom, twice. Richmond admits of his last stint: “They were two very tiring and exhausting years.”

Leaving the classroom has worked out for Richmond, and he is doing a commendable job thinking up rigorous system ideas for FE in a landscape where too few think tanks treat colleges, training providers, schools and universities on a par.

Perhaps, however, until his think tank – and other think tanks, and ministers – prioritise the policy crisis of workload and teacher demotivation, then bright minds like Richmond’s won’t make half the impact they really deserve to.