Young people from disadvantaged backgrounds are less likely to take up degree apprenticeships than to study at elite Russell Group universities, according to new research.

A study by the Education Policy Institute (EPI) has warned that the inclusivity of degree apprenticeships – a route promoted by government as an engine of social mobility – is falling short of expectations and risks becoming “another middle-class preserve”.

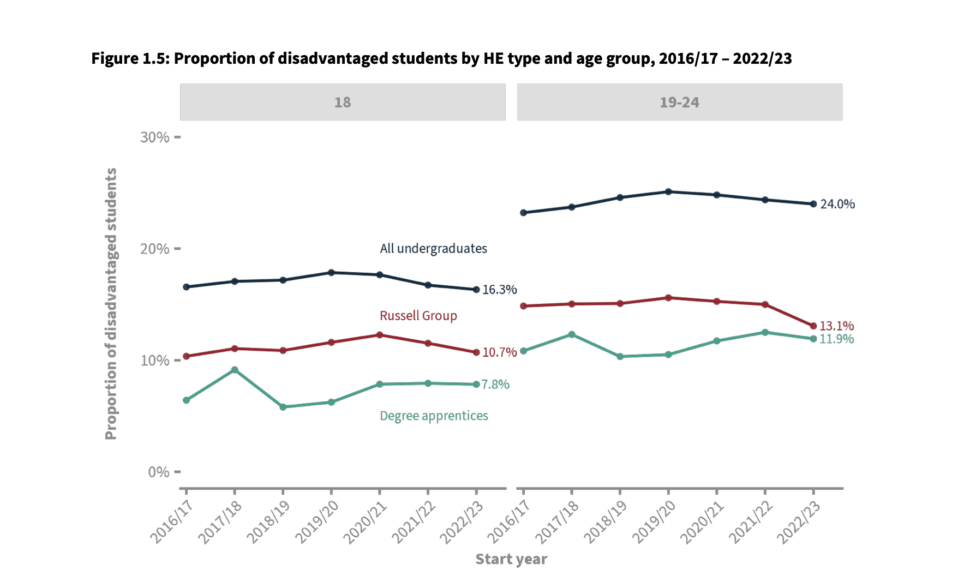

Using latest government data, EPI found that just 10.7 per cent of 18 to 24 year old level 6 degree apprentices in 2022-23 were identified as disadvantaged. That compares with 11.4 per cent of undergraduates at Russell Group universities, 19.4 per cent of all undergraduates, and 26 per cent of the wider 18-year-old cohort.

The findings suggest that degree apprenticeships, despite showing strong achievement rates and high post-graduation salaries, are currently “less inclusive” for disadvantaged young people than even the most selective universities.

Ministers and experts have warned of a middle-class grab on apprenticeships since 2018. Similar research by the Sutton Trust has urged officials to get a grip on access opportunities for degree apprenticeships.

Lee Elliot Major, professor of Social Mobility at the University of Exeter, told FE Week: “Degree apprenticeships have huge potential to be engines of social mobility – but only if they genuinely serve students from all backgrounds. We must do better in opening up these routes to all.

“It would be a huge national tragedy if, for all the rhetoric about expanding vocational pathways, they became another middle-class preserve, reinforcing the stark opportunity divides they were designed to close.”

Alun Francis, chair of the Social Mobility Commission and chief executive of Blackpool and the Fylde College, said it was “not a surprise” to find that degree apprenticeships have a similar profile to Russell Group universities in terms of socio-economic background as they “are in very short supply, so employers tend to seek out those with the highest grades”.

But, he added, “social mobility is not simply about diversity metrics; it’s also about how the economy grows and brings wider benefits across society. That’s what creates opportunities for all, not just the lucky few”.

The EPI urged the government to extend the reintroduction of maintenance grants for traditional degree students to include degree apprentices, and expand targeted outreach programmes to widen participation.

Degree apprenticeships boom

Degree apprenticeships were introduced in 2015 to offer an alternative to traditional degrees by combining paid, work-based training with university-level study. The model has been championed by ministers as a way to address skills shortages and open new pathways into higher education without tuition fee debt.

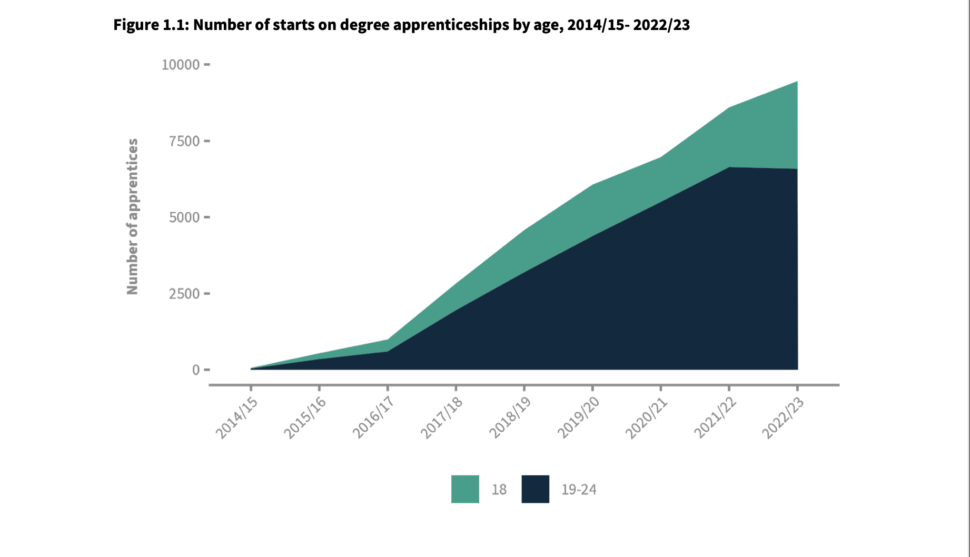

The EPI’s report said that following two years of slow growth, starts on degree apprenticeships rose rapidly from 2017.

Around 2,800 young people aged 18 to 24 started a level 6 degree apprenticeship in 2017-18 compared to almost 9,500 in 2022-23.

In 2023-24, the most popular sectors for young degree apprentices were health (27.5 per cent of the overall cohort), construction (22.3 per cent) and digital technology (16.9 per cent) sectors.

London remains the most popular place for young people starting a degree apprenticeship (19.1 per cent), followed by the north west (15.1 per cent). Take-up is lowest in the north east (3 per cent of all starts in 2023-24).

Achievement rates are higher among degree apprenticeships compared to lower-level apprenticeships. Degree apprenticeship achievement rates were 71 per cent for 16 to 18 year olds and 63.8 per cent for 19 to 23 year olds in 2023-24. That compares to the national achievement rate of 60.5 per cent.

The EPI said degree apprenticeship achievement rates are similar between students from the most and least deprived areas of England.

But the report also highlights stark differences in completion rates depending on where apprentices live and the sectors they work in.

Those training in social sciences had a 96.4 per cent achievement rate in 2023-24, while education trainees had 85.7 per cent and health degree apprentices hit 79.8 per cent.

At the lower end, business degree apprentices had a 57.1 per cent achievement rate, those studying in retail had 51.3 per cent and those in construction had 32.6 per cent.

EPI also found that apprentices from minority ethnic backgrounds – including Black African, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Indian, and those of mixed or other backgrounds – all show lower odds of completing their apprenticeship compared with White British apprentices, after controlling for other characteristics.

Call for action amid positive earnings data

Meanwhile, early earnings data shows degree apprenticeships can deliver strong economic returns. EPI exploratory analysis based on the latest two years of available data shows that one year after graduation, the average young degree apprentice earned around double that of the average young graduate – £36,785 vs £18,555 in 2020-21.

The report added that the “average young degree apprentice salary one year after completion remains larger than even degree-holders who graduated 10 years ago”.

However, EPI cautioned that these positive outcomes risk being undermined if disadvantaged students continue to be underrepresented.

David Robinson, EPI’s director for post-16 and skills, said degree apprenticeships were “a compelling alternative” to university, but warned that “it is now critical that the government and the wider sector actively work to widen participation and ensure this valuable route is open to all”.

Francis said: “We have chronic problems of low growth, static productivity and regional disparities. But the answer to this problem isn’t to start micro-managing who stands where in the opportunity queue.

“Quite simply, we need much stronger innovation and growth, and a rapid expansion of apprenticeship opportunities of all kinds — across the whole country.”

The government was approached for comment.