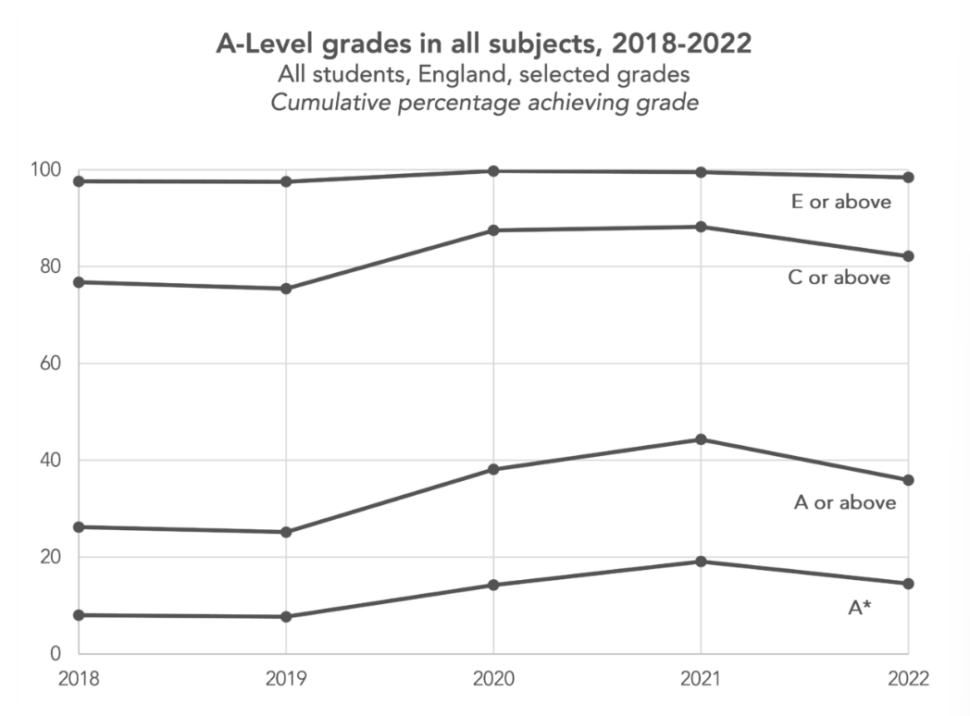

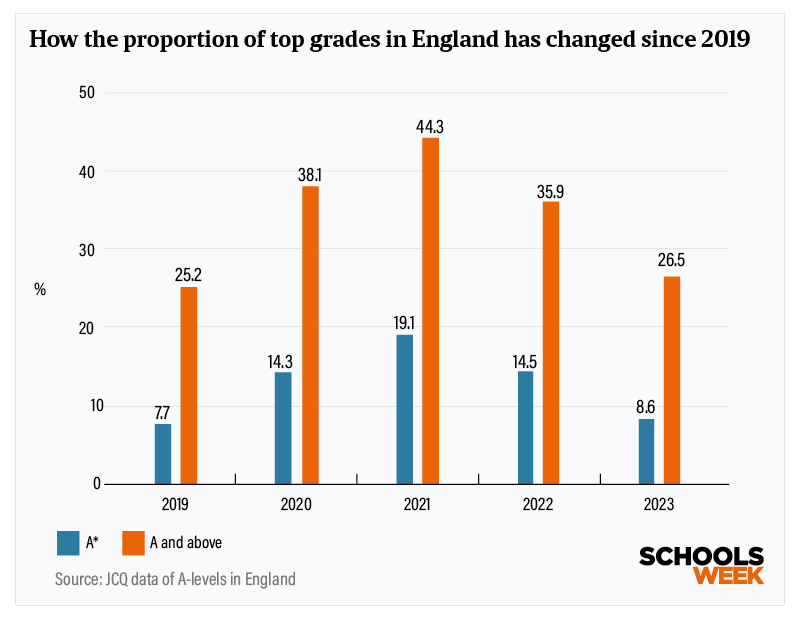

The proportion of top A-level grades achieved by England’s students dropped by more than 26 per cent this year, as results fell to near the same level as pre-pandemic 2019.

Overall, more than 67,000 fewer A* and A grades were awarded this summer, despite an increase in entries of more than 20,000.

This year, 26.5 per cent of grades issued were at A or above, down from 35.9 per cent last year and far below the peak of 44.3 per cent in 2021.

But this is still slightly higher than the 25.2 per cent in 2019.

The proportion of A* grades fell from 14.5 per cent in 2022 to 8.6 per cent this year, still up on the 7.7 per cent in 2019.

The government had asked Ofqual and the exam boards to return to pre-pandemic grading standards this year.

The Joint Council for Qualifications has published the results from the second summer A-level exams since the pandemic.

Students were awarded centre-assessed grades in 2020 and teacher-assessed grades in 2021 because of Covid disruption. This year’s A-level students were in year 10 when the pandemic hit, and like last year’s cohort did not sit GCSEs.

The proportion of grades at C and above fell to 74.4 per cent from 82.1 per cent last year, and is actually lower than the 75.5 per cent seen in 2019.

The number of students receiving three A* grades fell to 3,820 pupils, down from 8,570 in 2021. In 2019, 2,785 students achieved that benchmark.

Top grades almost back to pre-pandemic levels

The drop in top grades brings the situation within 1.3 percentage points of 2019. Exams watchdog Ofqual instructed exam boards to bring grades down again, after aiming for a “midpoint” between 2019 and 2021 grades last year.

However, the regulator also aimed to ensure that a student who would have secured a particular grade in 2019 would be just as likely to achieve that grade this year.

Dr Jo Saxton, Ofqual’s chief regulator, said students “should be proud of their achievements”, adding they had “shown resilience and determination despite the disruption caused by the pandemic during the crucial years of their education.”

“Two years ago we set out a clear plan to return to pre-pandemic grading – a system that schools, colleges, universities and employers are all familiar with. As we said then, we expected overall A-level results would be similar to 2019, and lower than in 2022.”

She said Ofqual had been “clear about this approach with universities and other higher education providers , and I want to thank them for showing understanding and awareness of the national picture when confirming places with students.”

But the north-south gap widens

London and the south east continue to outperform other areas, but the gap is now wider than in 2019.

The proportion of A and A* grades awarded this year was 30.3 per cent in the south east and 30 per cent in London, up from 28.3 per cent and 26.9 per cent respectively in 2019.

However, the proportion of top grades remains lower this year in the north east and Yorkshire and the Humber than pre-pandemic.

According to data published by Ofqual today, further education establishments and secondary moderns saw the biggest fall in top grades between 2022 and 2023.

The proportion of A and A*s issued fell by 34.9 per cent for FE establishments, 30.8 per cent for secondary moderns and 29.2 per cent for sixth form colleges.

The smallest falls were for private schools (18.3 per cent), free schools (20.9 per cent) and grammar schools (23.5 per cent).

‘A bruising experience for students and schools’

Geoff Barton, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, said all students “should be proud of what they have achieved”, saying falling grades is “not as a result of underperformance, but because the grading system has been adjusted.”

Paul Whiteman, general secretary of the National Association of Head Teachers, added that universities, employers and other providers “should take this into account when making decisions on places and offers.”

Barton added “whatever the rationale…it will feel like a bruising experience for many students, as well as schools and colleges which will have seen a sharp dip in top grades compared to the past three years”.

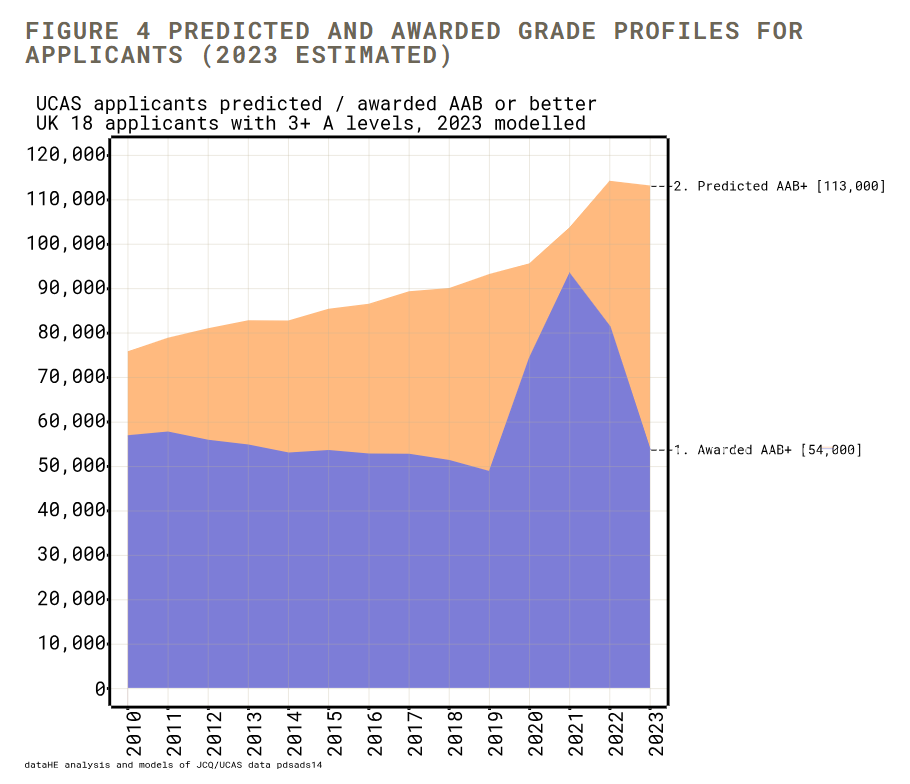

There were fears over falling grades resulting in more students missing offers for university or college.

But UCAS data shows 79 per cent of 18-year-olds in the UK secured their first choice plan, compared to 81 per cent last year and 74 per cent in 2019.

Nine per cent did not get their first or insurance choice, meaning they are now in clearing, which compares to 12 per cent in 2019, and 7 per cent in 2022.

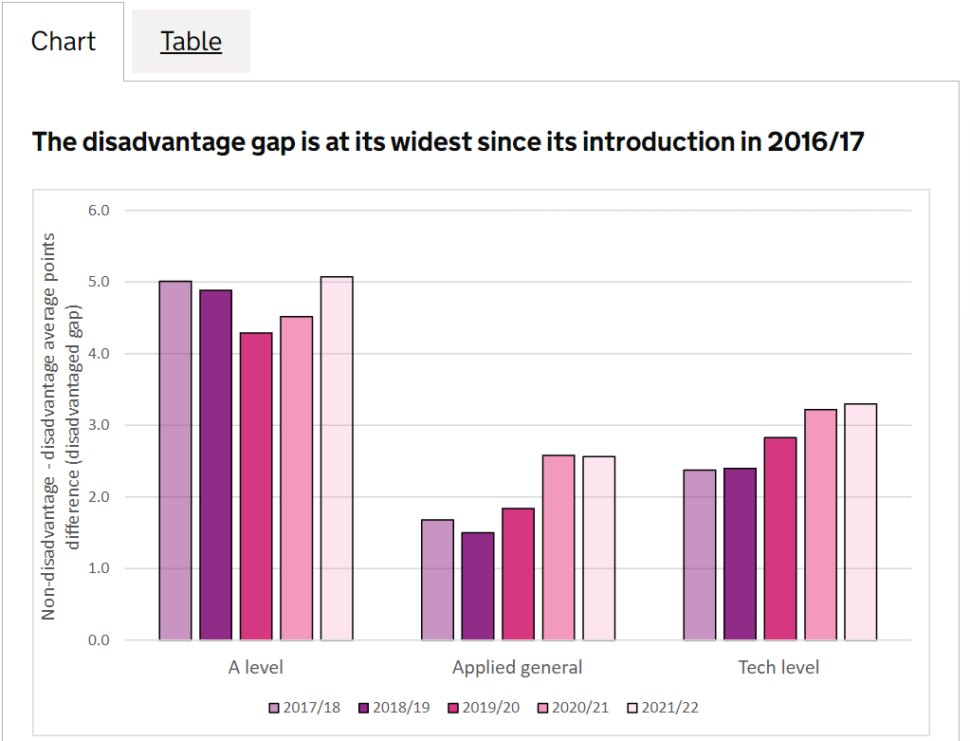

‘Widening participation challenges persist’

However for every disadvantaged student that got a place, 2.3 advantaged students progressed – compared to 2.29 last year.

UCAS boss Clare Marchant said “challenges in widening participation to the most disadvantaged students still persist.

“This demonstrates that we all need to continue the efforts to ensure the most disadvantaged individuals in society are able to benefit from life-changing opportunities in higher education and training, particularly as the 18-year-old population grows.”