This next white paper is critically important. Ministers must focus on the right measures, writes Naomi Clayton

The long-awaited levelling-up white paper is due to be published this month. Michael Gove, leading on the levelling-up agenda, has called it the “defining mission of this government”.

But with few details, many are struggling to understand what levelling up means, or to have confidence in it.

What do we know so far? There are four objectives: empowering local leaders and communities, growing the private sector and boosting living standards, spreading opportunity and improving public services, and restoring local pride.

A leaked draft paper outlines plans to deliver this through a “new devolution framework for England”.

So what would progress look like? We say that employment and skills must be a measure of success. The government should aim for tangible improvements in five key areas:

What would progress look like? Employment and skills must be a measure of success

1. Work

Employment rates vary from 90 per cent in East Cambridgeshire to 61 per cent in Gosport, Hampshire.

Geographic inequalities can be persistent: several of the high unemployment areas targeted by the 1934 Special Areas Act still have some of the lowest employment rates today.

2. Earnings

Average hourly earnings are partly a reflection of the types of jobs accessible in different parts of the country, and are one measure of the quality of work. Workers living in Blackpool earn less than half average earnings in Kensington and Chelsea.

3. Skills

Less than 60 per cent of people in Sandwell in the West Midlands are qualified to at least level 2 (equivalent of five good GCSEs), compared to over 90 per cent in Brentwood, Essex.

Regional disparities have widened over the past decade, with a 15 percentage point increase in residents in London qualified to at least level 2, compared with just ten percentage points in the north east.

4. Opportunity

Access to higher education can increase young people’s employment and earnings opportunities.

Only about a quarter of young people from state schools in Barrow-in-Furness in Cumbria go on to higher education by the age of 19 (including that delivered with further education providers), whereas closer to three-quarters from state schools in Harrow, Middlesex, do.

5. Child poverty

More than half of children in Tower Hamlets in London are estimated to be living in poverty, compared to one in eight in parts of Surrey.

Rates of child poverty are also high in other big cities, including Birmingham, Manchester and Newcastle.

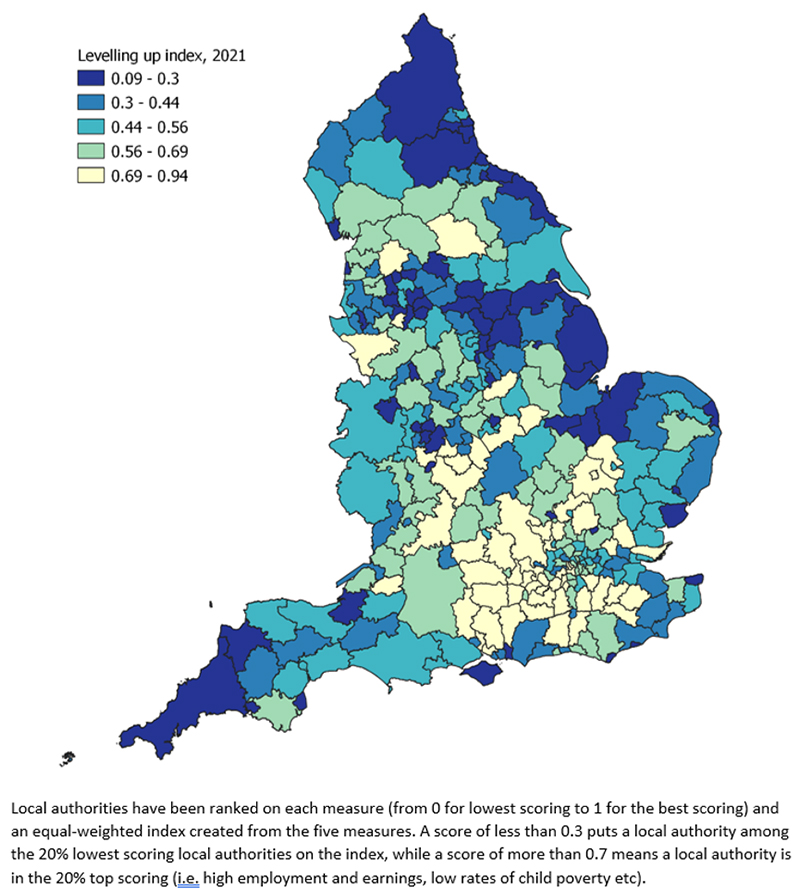

Combining these measures gives a picture of the neediest areas for levelling up (see the main image).

The areas that stand out in dark blue are noticeably coastal and traditional industrial areas.

Hull, a city that has struggled with the decline of its maritime and fishing industries, has one of the lowest overall scores, and many other northern areas sit in the bottom 25 per cent.

But there is no clear north-south, inland-coastal or urban-rural divide: London has some of the highest rates of child poverty.

Instead, skills are one of the most important determinants of economic prosperity. More adults need to upskill and retrain – but the cuts to adult education funding since 2010 mean fewer are doing so.

The government needs to go much further than the partial reversal of cuts in the spending review.

How that money is spent matters too. Local leaders are best placed to align policies and integrate services. We’ve previously argued for “local labour market agreements”, which could be used as the basis for devolution deals.

Meanwhile, the constant reinvention of policies around local economic growth, regional and local governance, and further education have created instability and fragmentation.

The government must develop a clear framework for devolution, showing what powers it is willing to devolve and compelling reasons for those excluded.

It needs to establish longer-term funding settlements for local government, moving away from resource-intensive competitive bidding rounds that make planning around local priorities difficult.

Improving opportunities and living standards for people in places like Blackpool and Hull requires a strategy built on greater institutional capacity that creates genuine, long-lasting, transformational change.

Good article, and a very interesting map. One thing stands out: in almost all the neediest areas – highlighted in dark blue – FE Colleges are the anchor institutions on the ground, delivering adult and higher education to communities others simply can’t reach. If we are to make progress in achieving points 3 and 4 – better skills and better access to higher education – then we should invest in FE Colleges and strengthen FE/HE partnerships to deliver more. Colleges like Blackpool & the Fylde, Dudley, Grimsby, Durham, the DNN Group in Lincolnshire and the RNN Group in Rotherham – and many more – are the unsung heroes of levelling up.