Young people fleeing conflict, oppression and destitution in their home countries are arriving in England in record numbers.

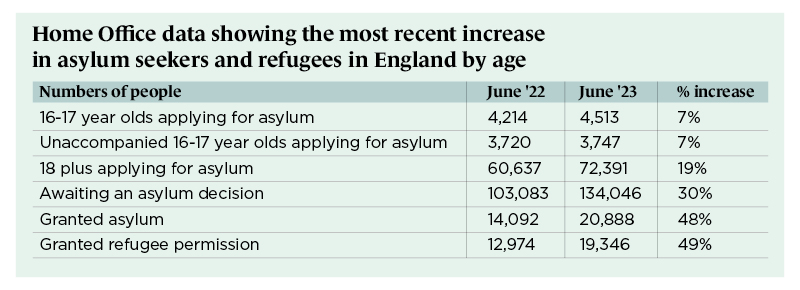

In the year to June 2023, 4,513 16 to 17-year-olds applied for asylum, up 7 per cent on last year. Eighty-three per cent were unaccompanied. Another 72,391 adults sought asylum, up 19 per cent on last year.

On arrival, young asylum-seekers and refugees face a myriad of complex and competing systems; legal, housing, benefits – and further education.

Hampered by strict course funding rules that limit supply in the face of growing demand, colleges and college teachers aren’t just providing education and training – they are on the frontline bringing all of those systems together to try and make them work for those young people.

Soaring demand for ESOL

Soaring demand for ESOL (English for Speakers of Other Languages) courses has left colleges scrambling to put on enough provision and provide the wraparound support these students need.

But Home Office decisions to move large cohorts into areas without giving local services time to prepare have left colleges struggling to meet those needs.

Refugee Education UK (REUK), a charity that helps refugees access education, researched the barriers that displaced young people face in accessing education.

Interim findings shared with FE Week show the biggest obstacle, cited by 49 per cent of the survey’s 140 FE respondents, was a lack of available provision, with courses described as being “often over-subscribed”.

While some colleges offer termly ESOL courses, others are annual, leaving prospective learners having to wait many months.

Megan Greenwood, coordinator for FE Colleges of Sanctuary, a network of colleges that have pledged to support displaced migrants, said one college opened up a course in the spring specifically for recently arrived Ukrainians. But the move was “not the norm”.

A Home Office policy to disperse asylum-seekers and refugees across England, reducing pressure on port areas, has led to placements in areas not accustomed to accommodating non-native speakers. This has left those migrants in some cases struggling to access any ESOL provision at all.

Some areas where the Home Office has placed large numbers of migrants all at once have been suddenly inundated with demand for ESOL.

In York, the arrival of 450 asylum seekers in the city last Christmas meant an “already stretched education system” had to find places for them, Greenwood says.

Luminate Education Group’s ESOL provision in Yorkshire grew from 3,404 in 2021-22 to 4,000 the following year; it also doubled the number of evening classes in Leeds this year.

Brighton, Hove & Sussex Sixth Form College (BHASVIC), which provides ESOL courses for 16 to 19-year-olds, increased its ESOL intake this year by 50 per cent and expanded it from a basic English qualification to English, maths and IT.

When Ukrainian refugee Iryna Samofalova moved to Colchester in July through the Homes for Ukraine scheme, she found it “so stressful and upsetting” to be told by the local Colchester Institute she would not be able to access ESOL provision for several months. However, she was subsequently offered a place on a higher-level course starting in September.

The institute currently has about 100 students awaiting ESOL assessment.

The surge in demand has left some colleges struggling to recruit enough ESOL teachers. West Yorkshire mayor Tracy Brabin told FE Week in June that colleges in her area were “desperate for tutors”, forcing her combined authority to propose setting up boot camps in ESOL teacher training.

Meanwhile, Luminate is appointing several ESOL teaching apprentices each year, and supporting teaching assistants to retrain as ESOL teachers.

Interpret funding rules ‘generously’

The Education and Skills Funding Agency (ESFA) funds 16 to 19-year-olds until the end of year 13, but after that, asylum-seekers are only eligible for central adult funding if they have lived in the UK for more than six months while the Home Office is considering their claims, or are receiving certain local authority support.

If they are refused asylum, they become eligible if they have appealed against this and no subsequent decision is made within six months.

All eligible adults can take English and maths up to level 2 if they do not have those GCSEs, and ESOL provision up to level 2 if they’re unemployed or on a low wage.

But Greenwood encourages colleges to take a “generous interpretation” of the funding guidance.

Colleges are “sometimes very nervous” to do so. But BHASVIC’s safeguarding manager Jackie Raybone said her college is “providing learning opportunities regardless of circumstances”.

BHASVIC ESOL teacher Jamal Salman admits ESFA funding “realistically isn’t enough”, with the “minimal” funding increase in recent years “subsumed by the rising cost of living and staffing”.

“All our ESOL students also have social workers and complicated lives that require additional support and advice. We are having to provide this without any additional funding.”

University of Bristol research into 16-plus migrant provision found “dedicated and talented teachers trying to support learners with complex and often poorly understood needs, in a highly fragmented education system”.

It also pointed to a “significant funding gap” for learners who “fall between the school-based and adult education budgets”.

While some colleges offer non-accredited ESOL courses for students unable to pass a qualification, others do not because “funding only goes with qualifications”, explains Oldham College ESOL teacher Eve Sheppard.

Those with “very low levels of education need several years of unaccredited classes” to get to the standard required for accredited courses.

The local offer

The cost and availability of adult ESOL provision also depend on decisions by local government, with some areas widening the scope of their ESOL provision to include other subjects while others have not.

Cambridgeshire & Peterborough Combined Authority is advising its colleges to package ESOL qualifications into a study programme to include maths or numeracy, digital skills, careers and “enrichment”, such as “life in the UK”.

As well as providing fully funded adult ESOL courses, it is “test[ing] new and innovative ways of delivering ESOL in the workplace” as well as funding training for ESOL tutors.

Surrey’s virtual school “may suggest” unaccompanied asylum-seekers under 16 join an FE setting rather than a school, to “minimise” the number of moves they have to make between settings.

But in some areas, cash-strapped councils are curbing their support of asylum-=seekers to save money.

Kent Council, which is at risk of bankruptcy, decided this month to restrict its offer of supported accommodation to unaccompanied asylum-seekers aged up to 18, changing the cut-off point from 21. Restricted services “may include” sessions on education and training, including opportunities such as apprenticeships.

Coping with trauma

Asylum-seekers and refugees often arrive with complex mental health needs. Unaccompanied children who are placed in unsuitable adult asylum hotels can be further traumatised.

The Local Government Association says the number of unaccompanied children in hotels “increased significantly” in June, with six in use and more in the pipeline.

Council sources in Plymouth and Warwickshire told FE Week the Home Office is now placing higher numbers of asylum-seekers into each hotel to maximise their use.

Camden Council leader Georgia Gould says some young asylum-seekers in her authority had been stuck in hotels for two years, which was “severely impacting their mental health”.

Community network Citizen’s UK’s senior organiser Froilan Legaspi describes asylum hotels serving “undercooked chicken and expired milk”, with “many young people staying there losing weight”.

Faheem, 16, a member of All4One – an unaccompanied young asylum-seekers group in Manchester – arrived in June 2022 from Calais, where he spent three days without food.

Nine months later he is still waiting to access any legal support, while another All4One group member has been waiting two years.

The wait is having a “severe impact” on Faheem’s mental health, and on his education: “I am happy that I go to college, I am trying to learn, but the problem is that you keep thinking about your family, waiting and waiting. All the books are in front of me, but I can’t concentrate. You are not sure whether you are going to have a solicitor soon or not. You don’t know what’s gonna happen to you.”

At BHASVIC, Salman believes the uncertainty around immigration status has a “greater impact” on learners than the trauma that brought them to the UK.

“Many” students are receiving CAMHS support, with ESOL teachers “regularly” dealing with solicitors, social workers, key workers, foster carers and the police if the student runs away from home.

“The social workers supporting these students are also overwhelmed and underpaid,” he says. “The expectations of what we can deal with as a college, beyond providing them with learning, is very high.”

Disappearing learners

Asylum-seekers and refugees can sometimes disappear from college communities altogether, either because they have been trafficked by criminal gangs, are evading the authorities to avoid forcible removal, or the Home Office has moved them on at short notice.

About 400 unaccompanied children have gone missing from Home Office-run hotels since July 2021. By June this year, 154 were still missing. The rest were found by the police either with people known to the children or at risk of exploitation by criminal gangs, according to children’s rights organisation ECPAT UK.

The Illegal Migration Act, which became law this year (but has yet to be fully enacted), stipulates that unaccompanied children be removed from the country when they turn 18, prompting concern from the Local Government Association that more young people will disappear shortly before their 18th birthdays.

If they stay, they would be denied access to further or higher education or vocational training.

Similarly, the Hub for Education for Refugees in Europe (HERE) say more children nearing their 18th birthdays are “likely to go missing from care or Home Office accommodation to avoid being detained and removed”.

Greenwood believes colleges are as yet largely unaware of this issue.

But Sanctuary has seen increased interest from colleges in anti-trafficking training because of concern over the exploitation of vulnerable students. “Colleges want to make sure they’re keeping an eye on these students, but at the same time, they don’t want to police them. It’s really challenging.”

Hotel life without education

Unaccompanied asylum-seeking children are entitled to access education within 20 days of arriving in the UK. But that legal duty appears to be rarely met.

Some members of All4One had to wait up to eight months for provision, and in the meantime were “bored”, “isolated” and “desperate to learn”, a recent report for Greater Manchester Immigration Aid Unit found.

Greenwood says that young people placed in hotels when they arrive have been “ignored and overlooked” when it comes to education.

But the Home Office says that “dedicated staff” are regularly based in hotels, including on weekends, to provide advice and signpost available English language instruction.

The government promised free English courses for Afghan refugees as part of the government’s Operation Warm Welcome scheme. But when Schools Week visited Afghan refugees at a hotel in Essex in July, young mothers described being offered only up to five hours a week of English lessons.

A government inspection of hotels for unaccompanied children last year found that “activities for young people were limited and comprised access to art materials, sport including swimming and football, indoor games, and some basic, perfunctory informal English language sessions”.

“By failing to provide any formal education or schooling, young people’s basic educational needs were unmet.”

Sometimes, the reason for the long wait for provision is down to confusion and miscommunication over what young asylum-seekers and refugees are entitled to receive.

Greenwood believes that college courses offered to these groups are “not very well advertised, both internally and externally”.

REUK’s survey found 41 per cent identified “unclear or inaccurate information about accessing FE” as a barrier.

Greenwood says in some instances asylum-seekers have applied for courses they believed were free, but were later “given a big bill they couldn’t pay”.

REUK’s chief executive Catherine Gladwell says: “Education is critical in enabling young refugees to build hopeful futures in this country. Yet every week we hear from young people who are denied education – sometimes for the simple fact that they are in temporary accommodation or have been given wrong advice about their eligibility.”

But efforts are being made to overcome these problems. Greater Manchester Combined Authority has created an ESOL Advisory Service with contact points in each borough.

Colleges going above and beyond

Staff at colleges across England are taking steps through food banks and donations to ensure their refugee and asylum-seeking students don’t go without.

At Hartlepool College, welfare officer Ronnie Bage is using his office to store donations for refugees that include bicycles and cooking equipment.

ESOL classes alone do not give young migrants the opportunity to mix with their English peers, but some providers have found creative ways to integrate them into the wider college community.

That’s especially true at the 19 Colleges of Sanctuary, which were awarded the status by the charity City of Sanctuary UK in recognition of their good practice.

Leeds City College has held listening sessions with ESOL students to better understand their college experience, introducing a training programme for staff to explore common misconceptions about asylum-seekers and refugees.

At BHASVIC, ESOL students felt segregated because their provision was “tucked away at the edge of the building”, so it was moved to a more central point, Raybone explains.

The ESOL tutor group was also combined with a mainstream A Level tutor group, and while this was later discontinued, Raybone recommends the initiative to other colleges.

The college is now seeking to develop activities with a “universal language” such as sports, music and art.

Your thoughts