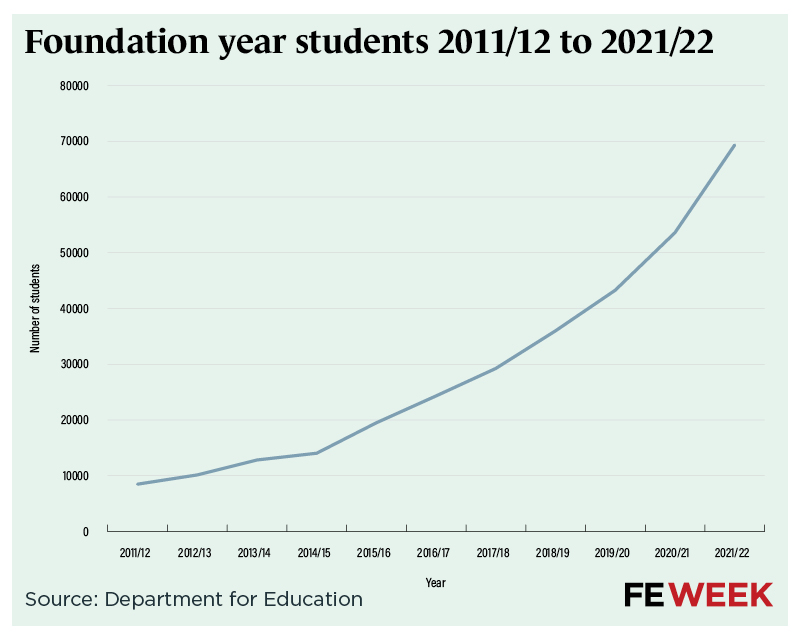

The number of students taking controversial foundation year courses at universities has rocketed by more than 700 per cent over the past decade, new figures reveal.

Ministers are currently clamping down on such higher education programmes which they claim are of poor quality. FE colleges have long viewed the foundation courses as a hindrance that pull students away from their own level 3 offers, such as Access to HE diplomas.

Ministers have sided with Philip Augar’s review of post-18 education and funding which was published in 2019. They are critical of universities’ use of foundation years to “entice” students on to degrees instead of the alternatives.

The government announced this year that it would slash the tuition fee cap that universities can charge for foundation years from £9,250 to £5,760 from 2025/26, making foundation year fees more aligned to Access to HE courses.

Exponential growth

New figures this week reveal the massive growth in foundation year courses over the past 10 years. A record 69,325 students took a foundation year course in 2021/22, up from 8,470 in 2011/12 – a 718 per cent increase.

Back in 2011, there were 678 foundation year courses available at 52 institutions. By 2021/2022, the number of available courses had rocketed to 3,717 across 105 institutions.

Much of the growth in provider numbers has occurred in London, where it shot up from 10 to 23. The number of providers in the South West increased from four to 10.

Business and management courses were by far the most popular foundation year subjects, with half – 35,580 – of all students taking such courses in 2021/22. The next most popular subject area was social sciences, with 6,915 students. The least popular courses were in veterinary sciences, geography and agriculture.

Fewer completions

Foundation years appear much more likely to attract older students, when compared with undergraduate degrees. One in five first-year undergraduates were aged 21 and above in 2021/22 compared with 64 per cent of foundation year students.

Foundation year students were also more likely to come from ethnic minority backgrounds: 46 per cent compared with 34 per cent of first-year undergraduates.

But they were also more likely to drop out: completion rates have hovered around 50 per cent for foundation year students for the past three years; for first-year undergraduates in 2021/22, that figure was around 80 per cent and for Access to HE courses it was 66 per cent.

Lower earnings

Graduates who take a foundation year generally earned less than graduates who did not, but a graduate’s decision whether or not to take a foundation year has had little impact on their progression to work or further study.

Median earnings of graduates who did not study on a foundation year were £3,700 higher on average than those who did. The only exceptions to this – where doing a foundation year had a positive impact on later earnings – were in materials and technology subjects, medicine and dentistry and veterinary sciences.

Graduates who took a foundation year were also less likely to be in high-skilled employment 15 months after graduating.

Outstanding student loan debt in 2003 was less than £10bn.

By 2013, it was over £50bn

At the end of 2022/23 it was more than £210bn

https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn01079/

Running along the same timeframe, social mobility metrics have consistently worsened and wealth gaps widened.

And despite having a higher proportion of degree level people in the workforce than ever, and low unemployment, productivity is stagnant. Yet the received wisdom is that higher level education translates to higher wages and productivity gains, right?

It’s almost as if aspiration and social mobility have been used as a tool to sell debt to the masses. The reality is that the debt burden ensures that the vast majority are put at a numerical disadvantage, stifling social mobility, suffocating aspiration and keeping the very few, very wealthy.

The trope that you are latching onto Robin is the Human Capital Theory illusion. If, instead, you look at education/higher education as self-formation and personal development as well as its social benefits, you may be less inclined to problematise it. I agree that this debt should be passed onto students and that the taxpayer should have a more prominent role in investing in higher education which is after all a public good, just like the healthcare system or the transport infrastructure.

Ah. I wasn’t attempting to detract from the notion of education for self development and enlightenment, rather an opening gambit to leverage open a discussion on economics, power and control more widely in the context of where humanity currently finds itself.

If you take a narrow view focusing only on the individual you lose sight of the combined impact of all those individuals. A individualised focus alone is only compatible in an environment of infinite resources where there is no need for a common goal, but that’s not the situation we find ourselves in.

Moving the burden of debt away from the state and on to the individual has shifted us away from intellectual groupies to intellectual selfies. It has a tendency of absolving individuals of their responsibility to society more widely by making them only accountable to themselves. It also makes many unenlightened debt pawns, perpetuating a broken economic model dependent on constant growth and incompatible with finite resources.

In that regard, higher education isn’t inherently a public good, just because we’re told that is what it is intended to be.

I take the view that if there is a problem, you problematise it. If you sweep too many problems under a carpet, it creates a trip hazard.