Colleges have seen a spike in ‘outstanding’ judgments as Ofsted prepares to close the door on the current inspection framework.

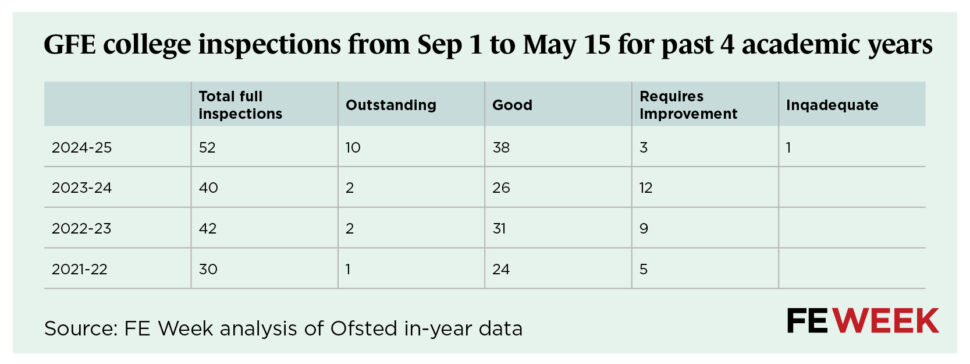

FE Week analysis shows that 10 of the 52 full inspections published for general FE colleges so far this academic year resulted in an overall grade one.

Ofsted had handed the top grade to just two colleges by this point in both 2023-24 and 2022-23, and to one in 2021-22.

Thirty-eight of the full inspections conducted so far this academic year for colleges have ended with a grade two. It means 19 per cent of full inspections in 2024-25 to date have been judged ‘outstanding’, while 92 per cent are ‘good’ or better.

This compares to 5 per cent and 70 per cent respectively for the same period in 2023-24, 5 per cent and 79 per cent in 2022-23, and 3 per cent and 83 per cent in 2021-22.

College leaders said the “remarkable” feat was a testament to the hard work of leaders and staff.

But an ex-inspector suspects inspectors could be being more generous in their grading as they approach the end of overall headline grades.

Ofsted said it would “caution against” comparing inspection outcomes across different years because “varying proportions” of previously outstanding, good, requires improvement or inadequate providers are inspected each year, as well as “differing numbers of providers inspected due to concerns”.

“This means inspection outcomes will inevitably fluctuate within and across years, so any trends identified are likely to be misleading,” a spokesperson said.

‘Amazing’ results

Ofsted is nearing the end of the education inspection framework launched by then chief inspector Amanda Spielman in 2019.

The watchdog, which ditched overall grades for schools in September 2024 and plans to do the same for FE and skills providers from September 2025, is currently consulting on the introduction of new-style report cards.

If green-lit, a new five-point grading scale will be introduced and applied to up to 20 categories for colleges. There will, however, be no headline rating.

There have been 224 full inspections published across the FE and skills provider base, excluding 16 to 19 schools and academies, between September 1, 2024 and when FE week went to press on May 15.

Of those, 14 per cent were judged ‘outstanding’ and 85 per cent were ‘good’ or better.

This compares to 8 per cent and 79 per cent respectively in 2023-24, 5 per cent and 64 per cent in 2022-23, and 7 per cent and 70 per cent in 2021-22.

FE Week broke the results down by the provider types, such as independent training providers, higher education institutions and adult and community learning providers, and found the most notable driver for the boosted results to be because of general FE colleges.

Gemma Baker, south east area director and senior policy lead for Ofsted at the Association of Colleges, said the increase in the number of ‘outstanding’ colleges “shows the amazing work colleges do and their quality of provision”.

Anne Murdoch, senior adviser in college leadership at the Association of School and College Leaders, told FE Week that the results are “testament to the hard work of college leaders and their staff” and are “all the more remarkable considering the financial pressures that colleges continue to be under”.

She added that while there will be a “degree of natural variation from year to year”, there is “no reason to think inspectors were being particularly generous”.

Inspection ‘nowhere near as rigorous as it used to be’

One ex-inspector, who did not wish to be named, said they “noticed” how inspectors got “more generous” towards the end of an inspection framework cycle during their time at the watchdog.

They also flagged that inspection teams are not always “adequately resourced”, especially for bigger college group inspections, which puts inspectors “on the back foot” and at a disadvantage as college leaders then have the “whip hand” from the start.

Some inspectors also “do not have the gravitas and necessary experience to ‘front up’ against the senior leadership teams of big college groups who are very formidable and expert as a collective”, the ex-inspector told FE Week.

“Ofsted leads have often never attained a higher position pre-Ofsted than head of department, assistant principal or similar. Indeed, very few, if any, senior inspectors have ever led a college or provider.”

They added: “There are lots of inspectors out there, current and ex, who will tell you inspection is nowhere near as rigorous as it used to be and is much more of a ‘fly by’ experience, particularly on big college group or training provider inspections.”

The 10 colleges to be judged ‘outstanding’ this academic year so far are: Newcastle and Stafford Colleges Group, City of Sunderland College, West Suffolk College, Bridgwater and Taunton College, Hugh Baird College, West Thames College, Nelson and Colne College, Cornwall College, New City College, The Education Training Collective.