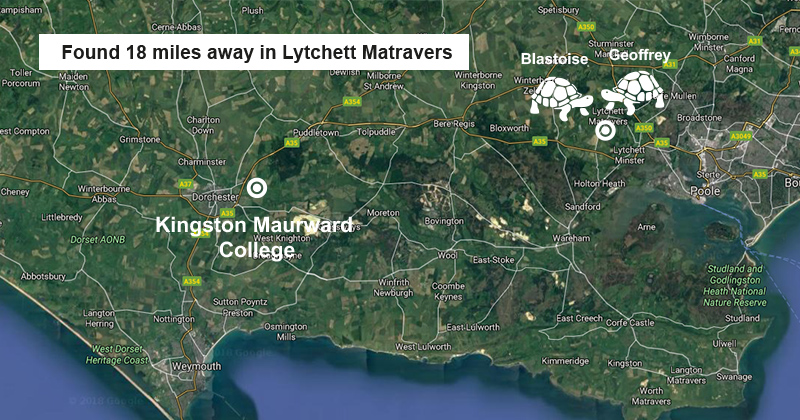

UPDATE: Two of the four missing tortoises have been found. Geoffrey and Blastoise were located in the village of Lytchett Matravers, around 18 miles from the college, Dorset police announced on Sunday.

Ms Hassall told FE Week the college was “very relieved” to have the pair back. They’re both off to the vets today as they’re “not 100 per cent” following their ordeal. Geoffrey has damage to his shell “and is quite snotty”, while Blastoise is “very quiet and not her usual self”, she said.

“Sadly no news on the other two so we are asking everyone to still keep their eyes and ears open”, Ms Hassall said.

The theft of four beloved giant tortoises has left a “massive hole” at a land-based college – although it remains hopeful it will see them again.

The quartet vanished on Wednesday night from Kingston Maurward College in Dorset, after thieves broke into the secure shed where they lived.

Sarah Hassall, head of the animal welfare and science department at the college, told FE Week how important the four had been to the college and to learners.

“Students at all levels can really get something from working with them,” she said.

Their disappearance had “left a massive hole” at the college but “we’re hopeful we’ll see them again”.

Three of the missing tortoises, called Squirtle, Wartotle and Blastoise, are female and aged 11, while the fourth is a 24-year-old male called Geoffrey (pictured above).

All four are around 40 to 50cm long, and 30cm wide, and are microchipped.

According to Dorset police, thieves entered the rear entrance of the college on foot overnight on August 22 and broke into the tortoises’ shed.

They then used wheelbarrows belonging to the college to transport the animals to a vehicle before driving off.

The four animals had been with the college for nine years, and their size means they will be difficult to replace, Ms Hassall said.

“They’ve all got their own personalities, and the students really engage with them,” she told FE Week.

Students on animal welfare and science courses at all levels worked with the four to learn a range of different aspects of animal care – including weighing, measurements, bathing and temperature gradients.

Geoffrey’s respiratory ailment meant students were also learning how to care for his illness, Ms Hassall said.

Not all the college’s students were aware of the theft yet, but those that were “really upset” and “shocked”, she said.

Police Constable Chris Stephens, of Dorchester police, said: “I am appealing to anyone who witnessed anything suspicious overnight in the area to please come forward.

“If you have any information that could assist with the investigation or have seen tortoises for sale in suspicious circumstances, please contact Dorset Police urgently.

“We are desperate to reunite them with the college to ensure they are appropriately cared for.”

Anyone with information is asked to contact Dorset Police at www.dorset.police.uk, via email 101@dorset.pnn.police.uk or by calling 101, quoting occurrence number 55180136179. Alternatively, contact Crimestoppers anonymously on 0800 555 111 or via www.crimestoppers-uk.org