The poorest adults with the lowest qualifications are the least likely to access training despite needing it the most, according to new Social Mobility Commission research, which has warned of a “virtuous and vicious cycle of learning”.

‘The adult skills gap: is falling investment in UK adults stalling social mobility?’, released today, looked at participation in, and spend on, job-related training and education in the last decade.

It found that training was often only available to people who were already either highly-paid or highly-skilled.

To address this imbalance, the report calls for greater investment by the government on education and training, more flexibility in how existing adult skills funding is spent, and better understanding by employers of the disparities in their training investment.

“Too many employers are wasting the potential of their employees by not offering training or progression routes to their low and mid-skilled workers,” said Dame Martina Milburn, the commission’s chair.

She urged both the government and businesses to “increase their investment in training” and to prioritise “those with low or no skills”.

“A lack of ongoing training for low paid workers is a contributing factor for millions to a lifetime of poorly-paid work,” said Alastair Da Costa, chair of Capital City College group, and a member of the commission.

The report’s findings are based on data collected from a variety of sources, including labour force and employer skills surveys, and research carried out by the former Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, among others.

It found that around a quarter of adults took part in job-related training in the last three months of 2017, and there was “evidence of a general decrease in the proportion of people participating in training” since the 2000s.

People from the lowest social grades were much less likely to take part in training than those from more advantaged backgrounds – and around half hadn’t taken part in any form of learning or training since leaving school.

Those in highly-paid, high-skilled professional roles were around twice as likely to have had some form of training in the past year than people in lower-skilled occupations: around 30 to 35 per cent, compared to around 13 to 16 per cent.

Dr Daria Luchinskaya, from the Institute for Employment Research, Warwick University, which carried out the research, said: “This report shows a ‘virtuous’ and a ‘vicious’ cycle of learning, whereby those with low or no qualifications are much less likely to access education and training after leaving school than those with high qualifications.”

According to the report, £44 billion was spent on adult skills training in 2013/14, of which 82 per cent came from employers and just seven per cent – or £2.5 billion – from the government, with the remainder coming from individuals.

However, the vast majority – £31 billion – of the employers’ spend went on indirect costs, including trainees’ wages, while just £2.8 billion was spent on fees to training providers.

Overall fees paid by employers fell from £2.9 billion in 2011 to £2.2 billion in 2015 – a drop of 24 per cent, according to figures taken from the employer skills surveys.

But at the same time “investment in management training has increased by 18 per cent suggesting that training for most other categories of employees has fallen”, the report said.

Government investment in adult training, via what was formerly called the adult skills budget, fell by 34 per cent in real terms over the same period, the report said, and was “at comparatively low levels internationally”.

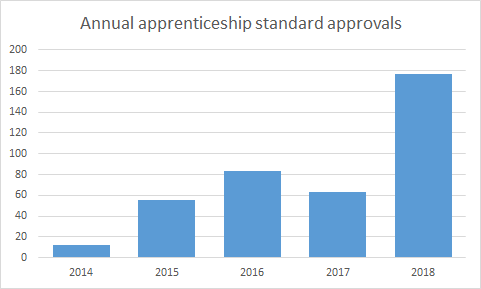

Today’s report comes amid growing concern over the rise in management apprenticeships, and the fear that that they are squeezing out those at lower levels.

Government figures published on Thursday showed that four of the top 20 apprenticeship standards with the most starts so far in 2018/19 were in management, including the level three team leader standard which continues to be the most popular.

Meanwhile, starts at level two have continued to fall.

Skills minister Anne Milton has vowed to “dig deeper” into the drop, and whether it’s linked to the rise in management courses.

A government-led national retraining scheme has been in development for the past 18 months, after it was promised in the Conservative party election manifesto in 2017.

However, information on the scheme – including how it will operate, who will be eligible and how much it will cost – has so far been thin on the ground.

A Department for Education spokesperson said: “It is vital that we continue to build the skilled workforce that businesses and the country needs to ensure we can compete across the world and adult education is a vital part of this. Last year the proportion of 19 year olds that hold a level two qualification in both maths and English was the highest on record.

“The Department has been allocated £1.5 billion for the adult education budget for each year up to 2020 and the Chancellor announced the £100m new funding for the National Retraining Scheme in the 2018 Budget to help adults retrain and upskill.

“In 2018/19 academic year we are supporting adults that are in work but on low incomes to access training through a one-year pilot scheme, and also helping employers invest in high-quality apprenticeships, to offer more people an alternative route into work.”