Colleges have hit back at the “unfair” English and maths condition of funding rule after FE Week found more than one in 10 had funding recouped for failing to meet its requirements.

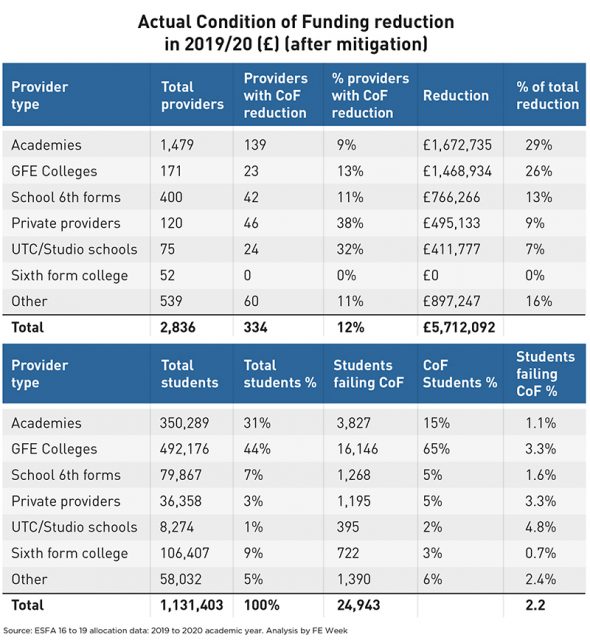

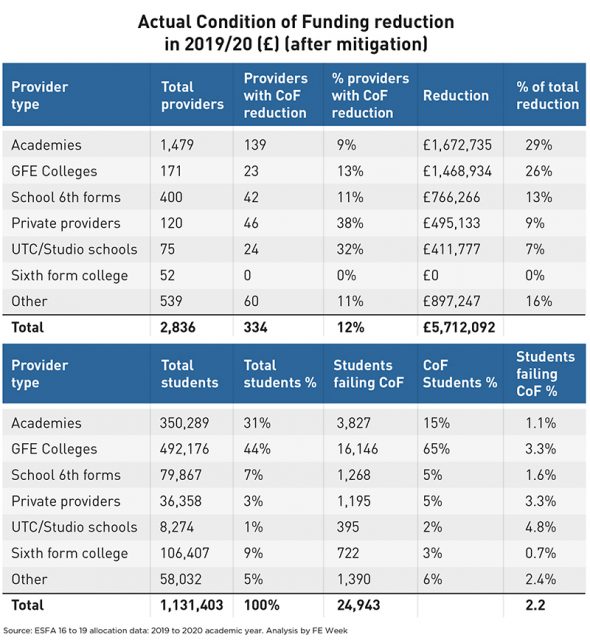

This newspaper’s analysis of the latest allocation data for 16 to 19 providers, released last week, revealed that 23 of the 171 (13 per cent) colleges in England have been stripped of £1,468,934 this year.

Four of them had more than £100,000 each withdrawn due to the controversial rule.

A spokesperson for London South East Colleges, which had £142,880 taken away, said the rule was “wrong and unfairly penalises colleges which take on high numbers of learners who arrive without good grades”.

“We carefully operate within the funding rules, and use a variety of methods to encourage English and maths participation,” they added.

“Only when these are exhausted, and there is no evidence of participation, are any learners removed from GCSE programmes.

“When this happens we support the learners to continue in vocational programmes which enable their progression into work or an apprenticeship.”

The Capital City College Group lost £212,386, the second highest amount out of all colleges.

A spokesperson told FE Week that GCSEs were “not appropriate for all young learners, which can be very challenging”.

The college acknowledged that it had “much work to do in this area” but said: “We absolutely stand firm that all of our learners are carefully assessed and placed onto what we believe are appropriate levels and programmes that best suit their individual needs.”

The spokesperson added: “We have recently developed a new maths and English strategy, which is already being implemented and monitored robustly.”

Under original Education and Skills Funding Agency (ESFA) rules, any student aged 16 to 18 who does not have at least a C (now 4) in their English and maths GCSEs, and who fails to enrol in the subjects, will be removed in full from funding allocations for the next-but-one academic year.

But the condition was relaxed from 2016/17, with the penalty halved, and only applied to providers at which more than five per cent of students did not meet the standard.

So only those providers with more than 5 per cent of students failing to enrol on eligible English and math qualifications saw their funding “adjusted” in the 2019/20 allocation.

New College in Swindon topped the list of general FE colleges with the highest withdrawal in 2019/20 – £213,481 – after exceeding the 5 per cent threshold with 281 eligible students not enrolled in the subjects. The college declined to comment on the figures.

West Herts College, which merged with Barnfield College in February 2019 and lost £93,664 in the 2019/20 adjustment, was the fifth-hardest hit by the condition of funding rule.

A spokesperson said the figures reflected the amalgamation of premerger performance data from both institutions: 193 students at Barnfield College and 141 learners at West Herts College did not meet the condition of funding.

“Since the merger, actions to improve the organisation and delivery of English and maths have been fully implemented,” they said. “This academic year, students enrolled on the subjects are engaging with their learning and attending lessons in line with condition of funding requirements.”

The latest figures for colleges show an increase from last year when 13 were deducted £1,137,091 to 23 colleges and £1,468,934 of funding withdrawn this year.

Elsewhere, 15 university technical colleges (UTCs) lost £180,966 under the rule and 46 independent learning providers had £495,133 deducted.

However, two UTCs that spoke to FE Week claimed that the figures used to calculate their adjustment level were wrong.

Silverstone UTC’s allocation data stated that 18 students did not meet the condition of funding threshold, which resulted in a deduction of £10,406 in this year’s adjustment.

But the principal Neil Patterson said there was an error in the management information system of the UTC which led to those students being incorrectly identified as not meeting the condition of funding.

“All 18 students did in fact meet the condition of funding, so we submitted a business case to the ESFA to seek to recover the amount,” he said.

“However, as the amount is smaller than the ‘5 per cent of revenue’ threshold that the ESFA apply, our business case was, unfairly in our view, rejected by the ESFA.

“We have since introduced a thirdstage check on this to make sure it doesn’t happen again, but feel that with post-16 funding being fairly complex, the threshold rule is an unfair barrier to receiving full funding.”

Another UTC also blamed initial inaccurate internal data and is attempting to restore the funding level. The Leigh UTC lost £19,300 after 12 students were registered on the system as not being enrolled in GCSE English and maths.

Principal Steve Leahey told FE Week: “We believe the information used to calculate the condition of funding adjustment was incorrect and we are in the process of discussing a correction with the ESFA.”

The ESFA said it is aware of the business case and will assess it once it’s been submitted.

In total, 24,943 students (2.2 per cent compared to total allocated) were not enrolled on eligible qualifications to meet the condition of funding rule.

But the biggest losers from the total £5.7 million reduction were academies, where 139 out of 1,479 (9 per cent) lost £1,672,735 from their 2019/20 allocation.

A Department for Education spokesperson said: “The government knows that students who leave school with a good grasp of English and maths increase their chances of securing a job or going on to further education. This is why students who do not achieve a standard GCSE pass at age 16 are given the opportunity to obtain it post-16.

“However, we recognise that for some students with a grade 2 or below, a Functional Skills Level 2 qualification may be more appropriate. These students can decide with their provider which qualification is best for them.”