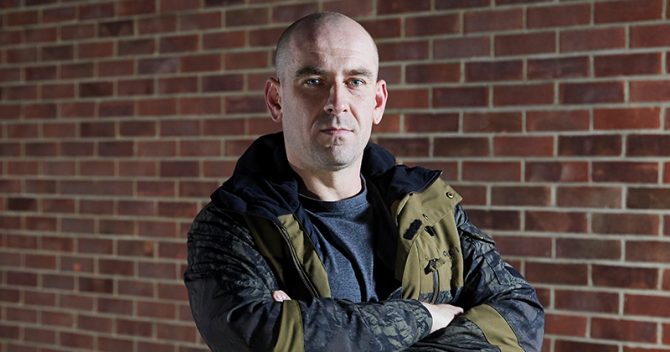

Grzegorz Bogdanski is being forced by the government to repay a £5,421 loan for an FE course he claimed he never started, or even realised that he had signed up for.

The 34-year-old construction worker said that all those involved have “washed their hands” of his case and described the Department for Education (DfE) as “the biggest disappointment” in the saga because of its lack of oversight over training providers.

Bogdanski is not alone. An investigation by FE Week has found that alleged victims of an advanced learner loans scandal are still being told that they must repay their debts, despite new regulations which give the education secretary power to clear them when their provider goes bust.

In June, in the wake of FE Week’s #SaveOurAdultEducation campaign, the DfE announced new legislation that would allow the government to cancel all or part of an advanced learner loan for those left in debt if their provider folded. This was to take effect from 1 July 2019.

However, the Student Loans Company (SLC) has confirmed that Bogdanski is still liable to pay his loan back as “records show that the learning provider confirmed his attendance on the course”.

FE Week has spoken to 12 other Southampton-based Polish building and construction workers who also claim that they have loans due for courses they did not complete with Edudo Ltd, which later collapsed. They said they plan to hire a lawyer and go to court over the payments.

Edudo Ltd was paid as a subcontractor by West London College, which held the contract with the Education and Skills Funding Agency.

Many of the victims claim that they had been sent “in circles” by authorities after receiving repeated requests to contact other institutions.

“There was something wrong… it doesn’t feel right”

Several also question how it was so easy for Edudo to receive funding and to claim to have delivered their courses.

Bogdanski attended an information session hosted by Edudo and a construction agency, named by other alleged victims as their employer AB South Construction Ltd, which is now also dissolved, in March 2015.

Some of the other members of the group, including Blazej Zielinski, 33, and Radoslaw Michalowski, 42, also claimed that they went to one or two initial meetings with the provider and later received letters notifying them of their obligation to repay loans.

They said they were told to sign multiple forms during the sessions but Bogdanski denies personally submitting them to the SLC or authorising Edudo to do so.

“After a while I said there was something wrong with it, it doesn’t feel right. I had my intuition but it was too late,” he added. “We were really tricked.”

Zielinski told FE Week that he was suffering from stress because he has to pay back almost £6,000 “for nothing” and Michalowski also confirmed that he never attended, or was offered, any training.

“I’ve got three kids and a wife and that money is a big problem for me. Everyone [is] just closing eyes and their ears,” he added.

Meanwhile Pawel Klak, 41, claims that he had received assurances from Edudo that they would cancel his loan application after he asked to pull out shortly after attending two meetings.

Klak, who said he has already paid back almost two-thirds of his loan, described the process of trying to contact Edudo, West London College and the SLC as being “like tennis… [sent from] one side to another”.

But Tomasz Lentkiewicz, 38, told FE Week that he had never attended any meetings or had any contact about the course with the provider or the employment agency with which he was registered.

“I think that was some fraud. Probably they use[d] my details to get a loan in my name,” he said.

Bogdanski went on to criticise the government, West London College and the monitoring of subcontractors like Edudo.

“Everyone is just closing their eyes and their ears”

“I don’t understand why the government or the Student Loans Company didn’t check them correctly because this is some kind of scam,” he said.

“They grab the money… and just disappeared without supplying the service they were supposed to.”

The ESFA has now banned the subcontracting of advanced learner loans, but this came too late for the alleged victims of Eduado.

After Bogdanski attended a six-hour meeting in March 2015, during which he completed paperwork, he sent his passport to the SLC, under the impression that he was just checking he would qualify for the loan.

Bogdanski then received a letter detailing the summary of his loan for an NVQ in Wood Occupations in April 2015; a total of £5,421, the maximum for the course as set by the government, had been requested.

It listed West London College (at the time called Ealing, Hammersmith and West London College) as the training organisation and stated that his course would start later that month and end in July, but Bogdanski claims that he did not attend it.

A spokesperson from the SLC said: “SLC processes applications for student loans in accordance with the DfE’s policy and on information provided by customers and verified by learning providers.

“In this case Mr Bogdanski applied for funding on 28 March 2015 and we received a signed declaration form from him on 31 March 2015.”

The SLC was not able to comment on all of the other learners at the time of going to press. However, a spokesperson said it was “satisfied” that some of the alleged victims’ attendance had previously been confirmed.

West London College confirmed that it “had a subcontracting relationship with Edudo for a short period of time between March and July 2015”. The subcontract was “not renewed beyond that date”.

Hampshire-based Edudo Ltd, which was allocated £500,500 in advanced learner loans, sold its “assets and business” to Learning Republic Group Ltd in November 2016 and entered voluntary liquidation.

Former Edudo boss Ronan Smith is currently the only director listed at Companies House for Learning Republic Group.

Bogdanski claims that he kept calling Edudo before it collapsed but the firm just “seem[ed] to just dodge” his attempts to talk to Smith.

Learning Republic Group has not responded to requests for comment from FE Week.

A spokesperson from the SLC said: “SLC has advised Mr Bogdanski that any dispute over his attendance should be raised with the learning provider and the ESFA, who regulate the education and training sector and are accountable for the funding paid to FE institutions.”

Bogdanski and many of the other alleged victims claim to have contacted West London College and the ESFA many times over the past four years.

Bogdanski described being left without any help or alternatives to sort out the situation as “very shameful” and “frustrating”.

“Life was good… and wasn’t so good after”

He added: “It is just like banging your head against the wall to try to do something. Everybody just turns their backs and says sorry we can’t help you.”

Another alleged victim, Marcin Tryka, 38, claimed to have knowingly signed up for the loan after being offered a gold CSCS card (for which level 3 NVQs are required) through his employer AB South Construction, but Tryka alleged that contact from Edudo was cut off after one site visit.

He said it “looked dodgy” from the beginning after the representative of Edudo spoke to a group meeting through a translator and therefore must have known “even if [they] go through the whole process [most people] wouldn’t get it [the gold card] if they can’t speak two words of English”.

Tryka said the ordeal put him “in a stupid loop where I couldn’t get enough money to think about getting a card”, impacting on his employment opportunities.

“It has been four years…, I [still] can’t believe it happened. Life was good and wasn’t so good after.”

Lukasz Pacuk, 36, echoed Tryka’s claims but said an Edudo assessor told him that no more site visits were needed after the first and that he would receive his certificate.

He had originally been enrolled on the Level 2 NVQ in Wood Occupations (Site Carpentry Pathway) in 2014 before being changed to Level 3 NVQ in the same subject.

“Everything [was] very, very strange. They played a game with everyone.”

FE Week has seen copies of correspondence from Edudo confirming Pacuk’s enrolment on both courses from November 2014 and June 2016 respectively, as well as a partially filled-in Edudo course book and other paperwork.

After Edudo collapsed, Pacuk claimed that he called Learning Republic and the company sent him his portfolio in the post but told him that he would not be able to continue the course and would have to take out another loan.

FE Week was also contacted by six other people who also claim to have been “cheated” by Edudo: Rafal Wojcik, Hubert Kot, Dariusz Kowalczyk, Jacek Major, Roman Trela and Damian Nowak.

College fails to say if subcontractor was monitored

West London College, previously known as Ealing, Hammersmith and West London College, entered into a subcontracting relationship with Hampshire-based Edudo Ltd “for a short period of time between March and July 2015”.

The college received the advanced learner funding directly from the Student Loans Company, before charging a management fee to Edudo, the subcontractor, and then paying them to deliver the course.

Many of the victims were not aware that West London College was their prime training provider.

The then Skills Funding Agency’s Funding Rules 2014 to 2015 stated that “a regular and substantial programme of quality-assurance checks” must be carried out on subcontractors.

West London College did not comment on whether Edudo was monitored during the period of training provision.

In 2016 the SFA announced that subcontracting within the advanced learner loans programme would be banned for all providers from the start of the 2017 to include the 2018 funding year.

Karen Redhead, who took over as principal at West London College in September 2018, said: “We welcome the FE Week campaign to highlight the plight of learners that have been left with debt but without qualifications, due to training providers going into liquidation.”

After being provided with the details of several other victims who alleged they had contacted the college and were turned away, Redhead admitted she was aware of three former students who had contacted the college recently and that, due to the “wholesale and multiple turnover of managers at West London College since 2015”, staff are now “piecing together evidence”.

She added: “We have been in touch with the Student Loans Company to obtain further information to help us understand the situation and to consider the best resolution for affected learners.”

Redhead maintained that the college was “absolutely committed to working with relevant agencies and individuals to resolve all outstanding issues as swiftly as we can.

“I would therefore urge those affected to contact the principal’s office directly so we can look into their specific circumstances and achieve satisfactory and timely resolution.”

West London College previously also had a subcontracting arrangement for adult education budget funding with SCL Security Ltd, a firm later suspended from delivering new apprenticeship starts, in a deal worth £1.7 million in 2018/19.

At the time Redhead confirmed that the college did not subcontract to SCL Security for apprenticeships but had terminated the relationship as a result of FE Week’s investigation.

This week Ofsted announced that it will launch research into FE subcontracting, after Eileen Milner, chief executive of the Education and Skills Funding Agency, sent a sector-wide letter last month warning that the agency was still investigating cases where subcontracted provision was not “appropriately controlled, overseen or managed by the lead provider”.

Changes to subcontracting contracts, to be phased in from 1 August and 1 December 2019, also for the first time require a “list of individually itemised, specific costs for managing the subcontractor”.

TIMELINE OF EVENTS

March 2015: Grzegorz Bogdanski attended a meeting hosted by Edudo Ltd, after which he was signed up to an advanced learner loan allegedly without his consent.

January 2017: FE Week reported on 500 advance learner loans students being affected by John Frank Training going into liquidation in November 2016. The firm left no assets despite recording a profit of £1.3 million in the first half of 2016.

February 2017: FE Week launched the #SaveOurAdultEducation campaign in Parliament after speaking to many victims with thousands of pounds worth of debt but no qualifications after their training providers collapsed. FE Week also revealed Edudo Ltd went into voluntary liquidation this month.

April 2017: The Department for Education asked the SLC to defer loan repayments for affected learners during the April 2017 to March 2018 tax year.

April 2018: Repayments were deferred again for the 2018/2019 tax year.

July 2019: The DfE told FE Week that the government would be able to clear learners’ advanced learner loan debt when their provider goes bust from 1 July 2019. Individuals are assessed on a case-by-case basis and past students should not be required to make repayments while their cases are being considered. Students who may be in scope of the new policy should be contacted by DfE or the SLC.

October 2019: Asim Shaheen, an ex-learner at John Frank Training who could not complete his training after the firm went into liquidation in 2016, told FE Week he had received no communication regarding the write-off, nor has Bogdanski.

November 2019: FE Week reveals how loans learners are still being told to repay their loans despite never completing the course or achieving their qualification.

It becomes clear that Ibrahim has identified her priorities as things she wants to improve, not lingering for a moment on what she hates or what she wants to do to The NUS. This, it turns out, is a deliberate strategy.

It becomes clear that Ibrahim has identified her priorities as things she wants to improve, not lingering for a moment on what she hates or what she wants to do to The NUS. This, it turns out, is a deliberate strategy.