Having become an MP in 1989, Lord Mike Watson has spent many years in frustrating opposition for the Labour Party. As he steps down as shadow education minister in the Lords, he offers words of advice for his successors

It’s not often you sit in a grand, wood-panelled room in the heart of Westminster, and the Lord sitting opposite you says: “I started out as a communist, you know.”

But that is where I find myself with the highly likeable Mike Watson, or Baron Watson of Invergowrie (which is his birthplace, a village on the east coast of Scotland). The shadow education minister for Labour in the House of Lords became an MP in 1989, was made a life peer by Tony Blair in 1997, and then got the education brief during Jeremy Corbyn’s tenure, in 2015.

He has worked with five shadow education secretaries, seen Labour education policies rise and fall, and had plenty to say in the recent debates in parliament on the then skills and post 16 education bill, now the skills and post 16 education act.

In 2005, he was even briefly kicked out of the party for setting fire to some curtains in a hotel while under the influence of alcohol, meaning his Wikipedia entry has to be one of the most colourful around (“Watson is a British Labour Party politician and arsonist.”) He tells me: “Both myself and the party have moved on, and I was very pleased to hold the education brief on the front bench in the Lords under two party leaders.”

But after seven years working hard at the education brief, he’s now stepping down and handing over to Baroness Jenny Chapman, former MP for Darlington, to spend more time with his family.

It was at university, he says, that he was “hit between the eyes with student politics”. He didn’t come from an especially political household – his father worked for a clothes trading company and his mother was a teacher – but at Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh he came across Marxist theory while studying economics.

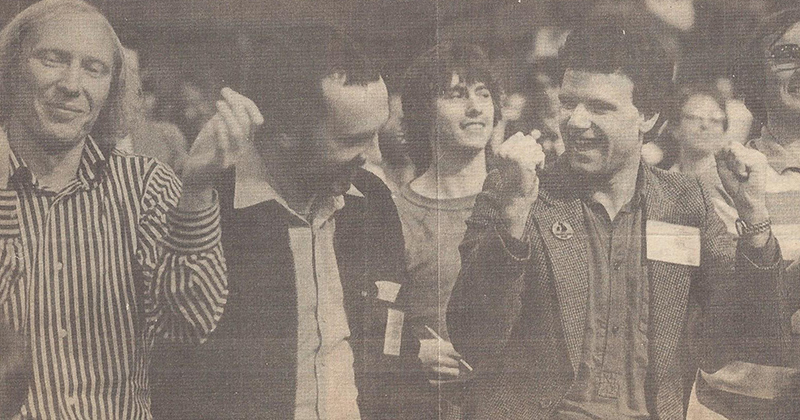

“In those days, student politics was really alive in a way it’s not now, and most weeks we’d be protesting the Vietnam war,” he says. “The debates were really rigorous. It wasn’t exactly preparation for real life, but it was a good preparation for debating in the chambers.”

But political reality soon hit home. He left university in 1974 and moved to Derbyshire to become a teacher with the Workers’ Educational Association, delivering adult education.

“It gave working-class people who had day jobs the opportunity to get the education they perhaps hadn’t got before,” he says approvingly. He taught multiple subjects and remains involved in the all-party parliamentary group on adult education to this day.

It was at this point he also decided the Communist Party had “good polemic” but little chance of power, and so, inspired by some of the Labour Party’s greatest figures, he switched to Labour.

Two of these influential figures were Scottish. Keir Hardie – a Lanarkshire man, like Watson – was one of the founders of the Labour Party in the late 19th century. Likewise, James Maxton was a Scot and former teacher who became a Glasgow MP in 1922 and was considered a powerful orator.

His other hero is democratic socialist the late Tony Benn. Watson grins as he recalls the story of Benn filling out a form including a section on his education, under which he simply wrote: “Ongoing.”

“These people were moving politics forward, and really improving people’s lives,” he says. “To me, that’s the purpose, to be in power and be able to change people’s lives.”

More soberly, he adds: “That’s why it’s been so disappointing to me that for so much of my active political life, Labour has been out of power.”

The party’s election history is indeed sobering: out of 28 general elections since 1918, the Conservatives have won 19 and Labour just nine. Watson admits that currently he “despairs” at the large Conservative majority, and the fact there is only one Labour MP in Scotland.

But he adds an important qualification: “I certainly think there’s a very good chance there will be a Labour-led government after the next election.” He’s not opposed to an SNP coalition, arguing the threat of a referendum is not as imminent as some may think.

So under a Labour-led government, what should FE policy look like?

First off, Watson breaks away from some in his party by voicing his support for the apprenticeship levy, a policy he clearly thinks merits continuation. “The levy has tended to be derided by some of my colleagues, but I’ve tended to me more supportive. Yes, the funding needs to be more carefully allocated […] but I think we should make the most of it. Bluntly, it’s a tax.”

If Labour had tried to introduce the levy, they would have been accused of hammering business

He adds the very interesting point: “If Labour had tried to introduce it, they would have been accused of hammering business. But the Tories can get away with it, and they have got away with it. So I wouldn’t look to junk it, I would look to revise and refocus it.”

Where he does have reservations is around the use of apprenticeship levy funding for degree apprenticeships. “I’m not anti-degree apprenticeships […] No debt, work experience, perhaps a guaranteed job – what’s not to like? But to call that an apprenticeship really is stretching it a bit, I think, and I don’t really want to see apprenticeship levy funds used for that.”

Watson also has little time for employers who complain about the 20 per cent off-the-job training requirement for apprenticeships (now dropped in favour of a minimum six-hour per week requirement). He points out “the historic record of British employers investing in training is appalling” compared with many northern European nations, adding “it’s such a short-sighted approach”.

His other calls are, like many in the sector, for the lifetime skills guarantee to be extended below level 3, and for funding for participants to do those qualifications, given the financial and caring responsibilities many are saddled with.

But as well as offering room for improvement on the bill, Watson gives credit where it’s due, too. “I’ve been less critical of the skills bill than some, because I do believe the government’s got its heart in the right place about boosting skills and lifetime learning.”

The other area he wants Labour to lead on is careers advice. Watson once started an apprenticeship in accountancy before quitting, and is frustrated “too many” schools aren’t promoting them and other routes into further education.

This is the key role of being in the Lords – providing a critical eye on the legislation of the day. But interestingly, Watson reveals Labour members in the Commons and the Lords don’t interact very much (the two houses even have different conventions: the politer Lords has ‘content’ and ‘not content’ votes, rather than ‘ayes’ and ‘noes’). For instance it was Angela Smith, Labour’s leader in the Lords, who handpicked Watson for the education brief in 2015, not Jeremy Corbyn himself.

Only she and Roy Kennedy, the shadow chief whip, also sit on the shadow cabinet, providing “that direct link back” to Labour’s top team, says Watson. Similarly, the Lords only has a soft power over the government (the many rejected amendments to the skills bill being a case in point).

“But ministers will be told, ‘the feeling in the Lords was strong on this, you might want to tweak that’,” explains Watson. He adds that Baroness Barran, the government’s education minister in the Lords, was “very receptive” to concerns in the House.

Instead the real problem within the Lords is the lack of staff, continues Watson. Shadow cabinet members might have one member of staff to research policy issues, but the Lords usually have none. “It does hamper you when you’re up against ministers who have civil servants.”

The lack of staff does hamper you when you’re up against ministers

It means his key advice to Chapman, his replacement, is to “build relationships and contacts” with sector organisations and think tanks who can offer answers, including the Careers & Enterprise Company, education unions, children’s rights groups and parent groups such as More Than A Score.

Watson concludes with similar advice for Bridget Phillipson, the latest person to be shadow education secretary for his party. He points out the most impactful education secretaries such as David Blunkett and Michael Gove “spent three years preparing” for the role and could “take down a folder of policies ready to go” once in office. “It really helps to be prepared.”

From the Communist Party to wearing gowns in the Lords, Watson clearly feels the education brief has been one of his most rewarding stints in politics.

“Education is just something we can all identify with. It has issues of importance and great interest to everyone,” he says. “It’s just a brilliant portfolio.”