Amid party conference season, it is easy to get lost in the flurry of policy announcements and commitments. Each sector vies for primacy, setting out its needs and a compelling case for investment and prioritisation. Stepping back, you begin to see common themes and consistent messages.

Persistent recruitment and retention issues are present in almost every sector, further exacerbating existing skills gaps. It has been encouraging to see, for the first time, a Skills Hub at the major party conferences, shining a light on these issues.

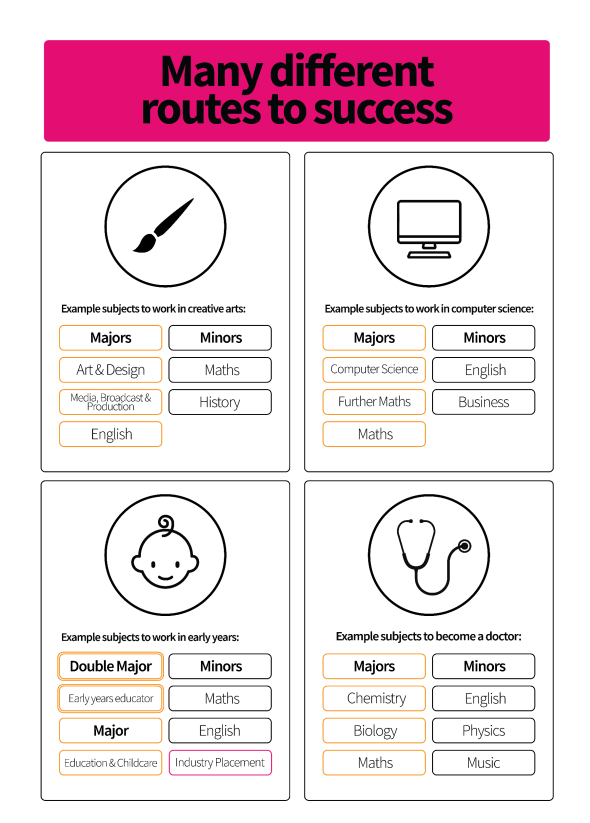

Further education plays an integral role in supporting sectors that are essential to the UK’s prosperity and productivity, now and in the future – from social care and early years to digital innovation. Yet we shouldn’t just consider what FE can do for other sectors; we must also recognise the importance of the sector itself and champion its needs. This point has been brought into sharp focus through data and expert insights in our new spotlight report.

Alongside skills gaps and workforce demand projections, the views of prominent voices including Association of Colleges chief executive, David Hughes, London South East Colleges group principal and CEO, Dr Sam Parrett CBE and NCFE’s head of policy, Michael Lemin present a stark and sobering picture. But what also comes through loud and clear is not just a diagnosis of the issues. There are tangible solutions to these challenges.

First and foremost, it is evident that we need to close the gap between school teachers and FE educators. But the challenge is much more complex than simply ensuring parity of pay. We are in a catch-22 situation whereby FE supports many industries that command far higher pay than our sector can offer. Individuals are trained up to enter well-paid jobs and are then reluctant to re-enter FE to teach. It’s both a credit to the career paths we forge and detrimental to attracting skilled professionals to the classroom.

We need to be ambitious, bold and assertive

We need to look at a broader set of measures, such as upskilling our existing educators. It’s something we’ve seen, for example, through the work we’re doing with WorldSkills UK on the Centre for Excellence. Since its launch in 2020, more than 2,000 educators have benefited from the programme which equips leaders and teachers with the knowledge and skills to raise the quality and standard of technical and vocational learning within their organisations. The programme’s next phase will see even greater numbers of educators in growth sectors such as digital, net zero and advanced manufacturing.

While much of the focus is rightly on the outcomes this produces for learners, what can’t be ignored is the impact this has on retaining people in the sector.

Another point that emerges from our report is the importance of industry partnerships – something we’ve long known to be essential. It’s this reciprocal nature that makes localised approaches so powerful – from relevant and accessible work placements to answering regional skills needs in a targeted way.

The overriding theme throughout the report is that FE can and must be a better champion for itself. In my experience, most people in our sector are modest, committed professionals who don’t seek the limelight. But we do need to do better when it comes to showcasing why it’s such a great sector to work in, the diverse opportunities it offers and the impact it delivers.

This all feeds into a wider need to raise the profile of vocational and technical education overall. Much has been done in this regard over the past decade, but we must not be complacent about the journey we need to go on with employers, parents and learners themselves. As well as vocal support from central government, it is vital that we have our own say in ensuring the sector is not overlooked. We need to be ambitious, bold and assertive about ourselves and for our learners.

This report (alongside upcoming others on social care, early years and digital) is designed as a conversation starter. It doesn’t contain all the answers, but it does add further weight to ongoing discussions and debates around the future of FE. Our work is too important for these conversations to go quiet.