Colleges are hurtling towards a staffing crisis that could derail the government’s growth ambitions, hike up costs and turn the youth NEET crisis into a disaster.

Faced with rapidly rising numbers of school leavers entering the sector over the next couple of years, leaders have told FE Week that sticking plaster solutions and expensive workarounds can’t be sustained.

Colleges have had to take drastic steps to keep priority courses running, including hiring teachers from overseas, recruiting former learners as teachers, and connecting learners remotely with teachers based hundreds of miles away.

Some are simply ditching courses in much-needed trade skills after failing to find suitable candidates in successive rounds of recruitment.

One college in a deprived part of the north of England which in previous years offered two level one, two level two and one level three course in electrical installation, construction and engineering, told FE Week that this academic year they could only provide one level one and one level two class for each cohort due to teacher shortages – denying dozens of aspiring youngsters the opportunity to qualify.

Last year, around 40 per cent of colleges reported being forced to cancel courses because of a lack of staff, an Association of Colleges survey found.

Despite government efforts to recruit and retain teachers in critical shortage areas through one-off cash incentives and a glitzy national marketing campaign, the situation could worsen with the number of 16 to 18 year olds set to rise from 2 million to 2.17 million in 2028.

This equates to an extra 60,000 students in colleges and sixth forms if participation rates remain unchanged, requiring roughly an extra 3,000 staff to teach them at a time when half the teaching workforce will be approaching retirement age.

Retention is also a problem. Almost half of FE teachers quit after three years, twice the rate of school teachers, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

The hardest gaps to fill

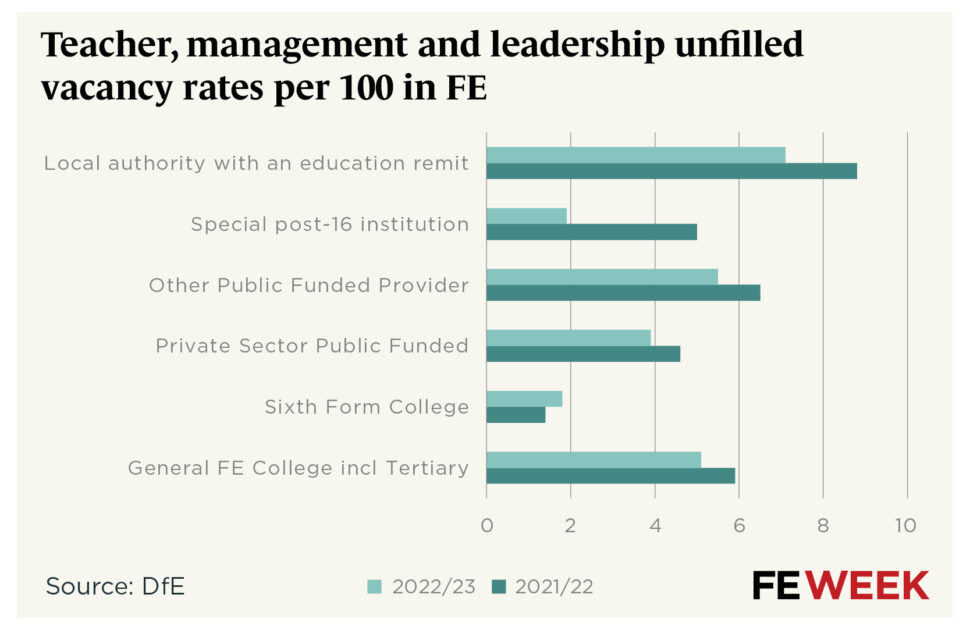

Government data suggests teacher shortages eased slightly; vacancy rates improved across the general FE and tertiary sector (from 5.9 to 5.1 per cent) between 2021-22 and 2022-23, and, anecdotally, colleges appear to be posting fewer job vacancies this year than last year.

But vacancy rates got worse in 2022-23 in 20 subjects, including computer science, maths and ESOL.

Some of the most challenging to fill have been those teaching subjects linked to the government’s “priority” industrial strategy plan sectors; advanced manufacturing, clean energy, creative, defence, digital, financial services, life sciences and professional and business services sectors.

The industrial strategy green paper highlights the UK’s “lack of technical skills – such as in electrical, mechanical and welding trades, key to the advanced manufacturing and clean energy industries – as well as basic skills in English and maths”.

The biggest challenge is the chasm between FE lecturing and industry salaries.

The National Foundation for Education Research last year found that teacher salaries in engineering and digital subjects were about 11 per cent lower than average earnings in industry, while construction earnings were about 3 per cent less (likely to be an underestimate as researchers were unable to consider self-employment earnings).

In 2021-22, the average general FE college had 17, 14 and 10 unfilled vacancies per 100 teaching staff for construction, engineering and digital, respectively.

£100,000 a year? There’s no way we can compete

By the end of 2023, West Nottinghamshire College’s engineering and construction department had 20 vacancies (which later dropped to 14), three of which had been advertised for five months or more.

One college principal FE Week spoke to spotted a job ad for a pipe fitter advertising a salary of up to £100,000 a year. “There’s no way in this world we can compete with that,” they said.

The latest government data shows the vacancy rate for functional skills teachers rose from 6.3 to 7.3 per cent in the year 2022-23, although this is likely to ease with the recent scrapping of the functional skills requirement for adult apprentices.

In the last two years, Ofsted reports have highlighted recruitment issues at general FE and tertiary education providers on 26 occasions, most commonly with reference to shortages of GCSE maths and English teachers.

The “not yet good” quality of North Hertfordshire College’s English and maths teaching and learning was put down to its “heavy reliance on using temporary agency staff”, while at City of Portsmouth College inspectors blamed staff vacancies and turnover for contributing to “high number of apprentices who do not complete their apprenticeship on time”.

DfE action

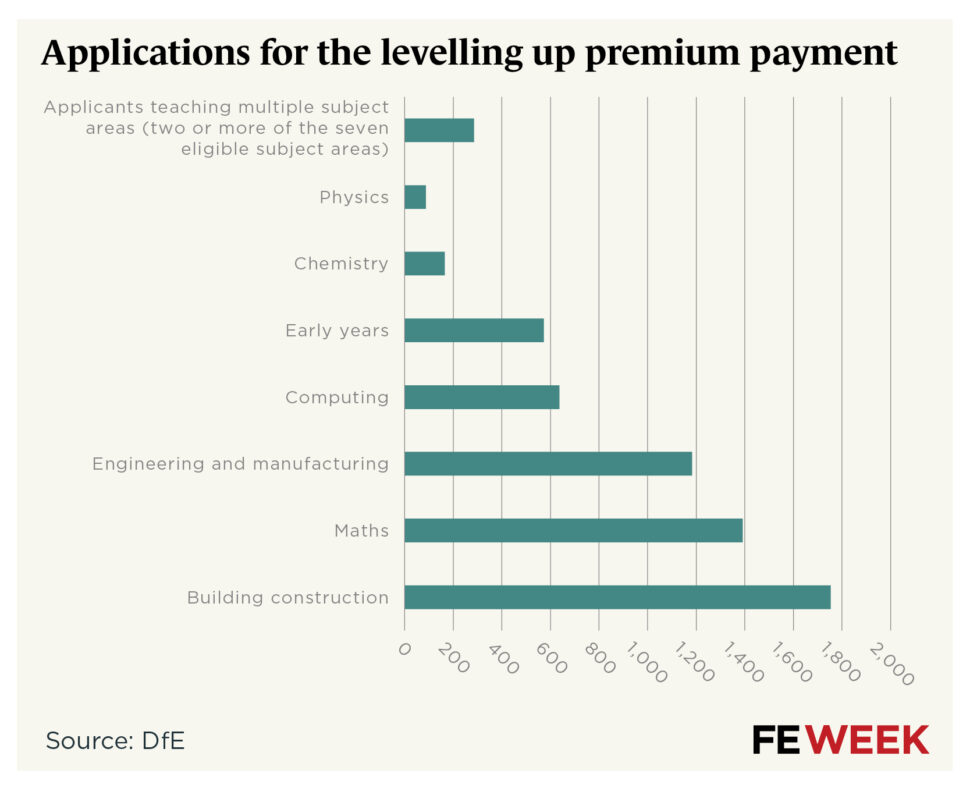

Amid mounting concern over teacher shortages, the government launched a £6,000 ‘levelling up premium’ payment for eligible recruits in seven hard-to-fill “critical skills priority” subjects, extending a scheme open to school teachers since before the pandemic to FE colleges too.

Applications close in March. By January 10, the scheme had received 6,075 applications, 29 per cent of which were for construction teachers, FOI data shows.

£24.3 million had so far been paid out for 2,876 approved applications (less than half of those applying).

Just 573 applications were received for early years teachers, who are vital to the government realising its plans to extend free childcare provision.

Anecdotally, principals told FE Week the scheme had not attracted any new teachers to their colleges but had provided “golden handcuffs” preventing current teachers from quitting.

Only FE teachers in the first five years of teaching are eligible for the scheme.

Labour’s headline-grabbing commitment to recruit 6,500 new teachers by the end of the parliament encompasses schools and colleges.

Skills minister Jacqui Smith said in an interview with the University and College Union that including colleges in the target “wasn’t necessarily a given … it was a particular decision to say that’s also got to relate to colleges.”

But we still don’t know how many of those 6,500 posts have been earmarked for colleges.

The DfE has also tried to boost FE recruitment by ramping up its marketing budget. Spending on ‘Share your Skills’ publicity (including Sky Sports News-style ads promoting FE’s “unique benefits”) rose from £2 million in 2021-22 to £5.1 million for both 2023-24 and 2024-25.

One principal said their college had not had any job applications arising as a result of the government’s campaign and their own marketing efforts had attracted just one potential candidate to teach bricklaying this year. Before Covid, a similar marketing campaign attracted 50 to 60 potential candidates.

School teachers to the rescue?

The government is also pinning hopes on a wave of school teachers opting to join FE, given that primary schools in particular will have less demand for staff; The Education Policy Institute research suggests a 4.5 per cent fall in primary pupil numbers between 2022-23 and 2027-28.

The government told the School Teachers’ Review Body in December that with “reduced demand in primary schools” it was “possible” that the looming 16-18 population bulge would “lead to increased movement of the workforce between the FE and schools sectors in common subject areas”. This “could also be a welcome opportunity for teachers to continue developing with new opportunities throughout their careers”.

Alex Quigley, head of content and engagement at the Education Endowment Foundation, believes there are “a lot of gains to be had” by primary teachers retraining in FE, as they are “really skilled in teaching a diverse range of students”.

He added: “So many students in FE may have barriers to learning which are equivalent to those in primary, such as limited writing skills, or difficulty reading.”

Education consultant Tom Richmond believes that while a specialist primary English or maths teacher “could well find they have a lot to offer” an FE college in supporting students studying entry level and levels one and two in these core subjects, it is “harder to envisage a primary teacher who has been through a traditional graduate teacher training route suddenly being able to switch into the technical and vocational provision that many colleges excel in”.

Two of Wigan & Leigh College’s maths and English teachers came straight from the schools sector, and principal Anna Dawe believes they bring a “richness” of experience with them. But encouraging a pipeline from schools to join FE “would be a hard sell”, given the widening pay gulf between the sectors.

The IFS found the median salary for college teachers to be £38,000 – 15 per cent lower than that of school teachers (£44,000).

While schools and academised sixth forms are implementing a 5.5 per cent wage increase for the full 2024-25 academic year, sixth form and general FE colleges were given a ‘one-off’ £50 million grant to only offer the equivalent wage rise for their teachers covering the period between April and July 2025.

The IFS said the pay gulf with schools is likely connected to the high exit rates amongst college teachers, with 16 per cent leaving their jobs each year.

Turning to agencies

Colleges have turned to recruitment agencies to keep classes running, but this has led to spiralling costs and, in some cases, lowered the quality of teaching.

New College Durham spent £901,000 in 2022-23 and £821,000 in 2023-24 on contracted-out staffing services using “external agencies to ensure there was no break in learning”, its 2023-24 accounts said. It added: “The high cost was largely due to the difficulty in recruiting posts across the curriculum as national labour shortages led to delays in recruitment.”

Chelmsford College’s current risk register highlights “agency cost controls”, stating that “retention and recruitment of permanent staff continues to drain resources due to parity of salaries with schools”.

Chelmsford is currently advertising for 14 roles, including brickwork, electrical and plumbing lecturers.

Its last Ofsted report in March 2024 highlighted how “leaders use a high proportion of agency staff”. “In English, mathematics and electrical, this impacts negatively on the quality of learning”.

Heart of Yorkshire Education Group’s latest accounts mention “real challenges” around staff recruitment and “reliance on costly agency workers to fill a number of vacancies, particularly for engineering and construction courses”.

It’s driven by low pay, high workload and competition

One principal told FE Week their recruitment costs had “gone through the roof”, with yearly spend now double what it was before Covid.

Last year they went to market eight times to recruit an electrical lecturer, each time racking up new costs.

One of the largest FE recruitment specialist agencies is The Protocol Group, whose business solutions director James Schofield says rising FE teaching shortages are being driven by “low pay, high workloads and fierce competition from other industries”.

He believes the most acute shortages are for specialist engineering, digital and healthcare teachers, and sees high demand also for careers advisors and job coaches.

But Schofield believes that over the last decade colleges have moved from reliance on temporary workers to more permanent contracts, “driven by the demand for niche skill sets”.

For example, sessional construction teaching was becoming “less attractive for candidates as temporary pay rates were not competitive with the industry”.

“Colleges, therefore, started recruiting these roles on a permanent basis, offering better packages, pensions, and benefits than the construction industry.”

Whereas three years ago around 60-66 per cent of his college clients’ workforce were sessional, now he believes it is 50 to 55 per cent.

Innovating to keep provision going

Some colleges have turned to technology to provide a solution to local shortages of specialist teachers.

I-Immersive’s ClassView platform leverages virtual and augmented reality to connect classrooms across geographical boundaries.

22 skills providers led by London South East Colleges (LSEC) installed connected immersive spaces, including New City College and Newham College.

The technology is also being embraced by USP College in Benfleet, Essex, where chief executive Dan Pearson (also an advisor for I-Immersive) believes there are “simply not enough” college teachers in many parts of the country, “particularly in rural or economically disadvantaged areas”.

Its technology means that “a student in a small town in the north of England can now have the same access to a top-tier maths teacher as a student in central London”.

Bolton College has invested in staff wellbeing to boost teacher retention. Its last Ofsted report in November pointed to “stabilised” curriculum team numbers in some departments. Teachers “particularly appreciate leaders’ investment in an artificial intelligence tool” to help with lesson planning, and “report favourably” on staff meditation and financial wellbeing sessions, and a menopause café.

In the past you’d just recruit an experienced tradesperson

Harlow College was praised by inspectors for being “creative” in addressing “challenges” recruiting for engineering and aircraft maintenance engineering teachers by “gaining a sponsor licence to employ staff from overseas” – although staff turnover in these areas still remained “high”.

Hartlepool College of Further Education bolstered its electrical department by recruiting two former level three students with some industry experience to “help out and ultimately teach”, says principal Darren Hankey.

“Whereas in the past you would just recruit an experienced [tradesperson] to hit the ground running, now there’s a lot more work for us to do to get them up to speed,” he says. “They’re shadowing our maintenance team to make sure they’ve got the right skills before we let them support our apprentices.”

Schofield predicts “increasing demand” in the next three years for specialist staff in higher-level apprenticeships, renewable energy and AI, “where industry experience is crucial but hard to attract due to pay and conditions in FE”.

But with the number of 16-to-24 year old NEETs now nudging a million, the highest increases in demand are likely to be for the low-level practical courses which are already currently among the hardest to recruit into.

Hankey said that in Hartlepool, “many of those at risk of becoming NEET, who didn’t realise their potential at school become engaged in technical education, whether it’s laying a brick wall or plumbing a bathroom. Not only are those courses helping the government meet its house building and industrial strategy targets, they’re also helping to keep those young people at threat of becoming NEET on board.”

Your thoughts