When an FE commissioner’s report in April laid bare the extent of the governance failures at Weston College, its chair, Andrew Leighton-Price, was “shocked” by most of its findings.

The report revealed how £2.5 million of concealed payments had been made to its principal, Paul Phillips, between 2017 and 2023, with some of its governors being unaware of the extent of his pay package.

When confronted with the report’s findings, Leighton-Price, who was Weston’s chair from 2019 to 2024 and previously worked in IT and accounting, said he believed governance “probably hasn’t kept up with the demands of the modern FE college”.

Many might agree with him.

Governing boards are expected to hold their executive teams to account for the educational performance and financial health of their college. But lately, evidence of governance failures is prompting calls for more to be done to professionalise the sector.

Since the Weston scandal erupted, colleges have received increased correspondence from the FE commissioner and the Department for Education (DfE), hammering home the importance of good governance.

When Burnley College, which claimed to be “number one” in the country for 16-19 achievement, was found by Ofsted to have “misled” by inflating its data this year, the watchdog noted how its governors had “limited experience of the further education and skills sector”.

“For too long, those responsible for leading and governing Burnley College did not question exceptionally high achievement rates or ensure that internal policies and processes were robust enough to manage the risk of inaccurate achievement data,” it said.

Limited expectations

But some believe there are limits to what can be expected from unpaid volunteers, and that the DfE should make it easier for colleges to pay their chairs.

A post-16 white paper expected from the government will introduce more accountability through new “regional improvement teams”. It is unclear where they will sit alongside Ofsted, DfE financial oversight, the apprenticeship accountability framework, local skills improvement plans and college accountability statements.

The theory goes that colleges offering renumeration could recruit better-qualified chair applicants who could be held more accountable for the decisions their boards make.

FE commissioner Shelagh Legrave is in favour of renumerating chairs. Speaking in a personal capacity, she said chairing can involve a “significant contribution of time”, particularly if that college is “large” or “in difficulty”.

“Excellent governance is a key component of an outstanding student experience and delivery of a college’s mission. Chairs give voluntarily substantial amounts of time to college boards. I am in favour of allowing colleges to pay their chairs an honorarium.”

Which colleges are paying chairs

As exempt charities, colleges must seek permission from the Charity Commission if they want to pay their chairs.

But the commission will only consider allowing a college to do so under certain conditions: if the college is undergoing “significant change”, such as a merger involving additional workload; if they are unable to recruit an unpaid chair and are seen as failing; or if the role is considered highly demanding because of the college’s “size and complexity” and recruitment attempts have failed.

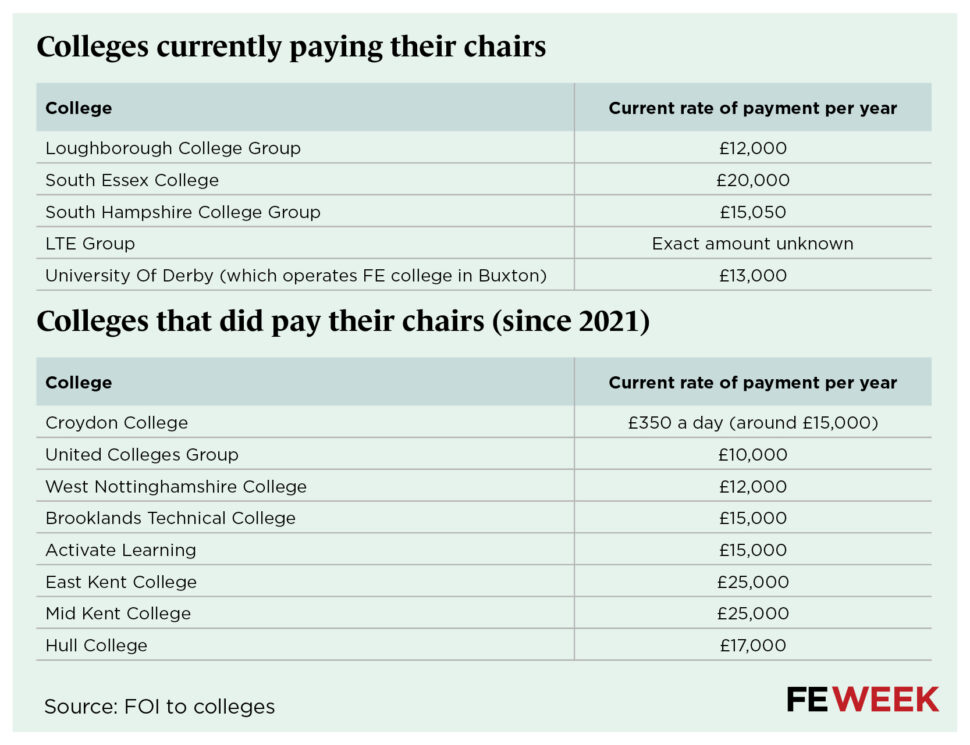

At least 14 colleges and college groups have paid their chairs since 2016, our research revealed. Of 166 colleges and college groups that responded to our freedom of information request, nine previously paid their chair (including eight since 2021) while five are currently doing so.

Other colleges have sought permission to pay their chairs but have been refused.

In 2023-24, the Charity Commission declined one application, “advised” two and approved four. Last year, it declined two, advised two and approved three.

‘Painful’ process

Governance expert Ian Valvona, who has chaired multiple colleges, pointed out that the application process involves “quite a lot of paperwork”, and the commission does not “nod them through”.

Some colleges pay consultants to “make the argument for them”.

“You can get these cases through, but you have to really invest in it,” he added.

Paul Aristides, partner at executive search firm Anderson Quigley, is aware that “a number of colleges have considered or are considering paying their chairs for the first time but have not taken this forward with the Charity Commission”.

One director of governance told FE Week that their college group had agreed to renumeration, but the “painful” application process, which involves answering around 30 questions, is “designed for you not to get through the process” which feels “terribly unfair”.

“Finally, you get to the end if you haven’t lost the will to live and get this automatic response that somebody will get back to you in 12 weeks.”

The director believes it is “shocking” that, as organisations with multi-million pound turnovers, colleges are “placed in the hands of unpaid volunteers to oversee”.

“My chair does an awful lot. It just kills me that we are not paying these people for this amazing work they are doing.”

Valvona believes that with FE colleges becoming “more complex” in the last 15 years, as “large, complicated businesses, you want someone as chair who isn’t in that community volunteerism space, who is held to account for the work they put in.”

But not everyone agrees. Rob Nitsch, chair of City of Portsmouth College, is “very wary” of a “paid-for approach”, having “seen this turn relationships to the transactional and away from the vocational”.

He believes this is “not the time to be advocating for financial resource for governors”.

“Rather, I think there should be more work on the governor offer to make it more attractive, to increase the sense of reward and to make more of the civic responsibility that goes with it.”

Similarly, Hull College’s chair Rob Lawson does not believe that “paying people – from a seemingly ever-decreasing pot – would necessarily raise standards or increase the pool of potential chairs”.

Other sectors

The higher education sector is also facing calls to pay chairs. A 2023 paper for The Committee of University Chairs found that “more questions are being raised about the long-term suitability of the volunteer governance model for higher education institutions”.

In 2019, seven universities were paying their governing body chairs between£15,000 and £25,000 per year. Two also paid committee chairs up to £7,500, a report for the Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI) found.

The University of Derby, which also operates FE provision, currently pays its chair £13,000 a year, because the “time commitment” and “complexity” of FE and HE business was “significant and worthy of remuneration”.

Outside of education, paying governors (or trustees) is more commonplace. All NHS trusts and many housing associations pay their governors, with chairs earning between around £20,000 and £40,000 a year.

The last time the government reviewed FE governance, in 2013, then-skills minister Matt Hancock decided against paying college governors. His review claimed that if the NHS remuneration strategy was introduced to FE, this could cost a college nearly £200,000 a year (assuming that 13-15 business governors were paid per college) which “could place a huge financial burden on many colleges”.

FE Week understands that DfE officials edged closer to getting ministers to agree to pay chairs just before Covid. But there now appears to be little appetite among cash-strapped ministers for it.

“The DfE has not been particularly supportive of remunerated chairs or board members in FE,” said Aristides.

Although he believes there is an “ever-growing case for chairs to be paid” given the “increase in accountability, complexity and time commitment” of these roles, Aristides concedes that it is a “divisive” topic and “a look that jars with a sector often struggling financially”.

Similarly, one chair to whom FE Week spoke said there was a “stigma attached” to paying a chair and colleges do not want to “feel like an outlier in the sector”. “But if you want to get people who roll their sleeves up and lean into an organisation, and not just sit back with ‘strategy awaydays’ and delegating write-ups to their CEO, then you need to pay them,” they added.

Payments in challenging circumstances

Colleges placed in intervention are often expected to appoint and pay a new, DfE-approved chair, who is typically someone with departmental connections.

But not all such chairmanships end happily.

In 2019, after Brooklands College was stung by an apprenticeship subcontracting scandal that left it reeling with a £25 million debt to the Education and Skills Funding Agency, the FE commissioner parachuted in Andrew Baird, a national leader of governance and chair of Orbital South Colleges, to aid its recovery mission.

Baird was paid £15,000 a year to help the college draw up plans to bring it out of the red. But the payments stopped in November 2022 when he resigned from both his chair roles, after sharing a meme about Rishi Sunak in a WhatsApp group that some considered racist.

Sometimes, complex challenges emerge that chairs (whether paid or not) struggle to deal with.

United Colleges Group was given approval to remunerate its chair, Tony Johnston, £10,000 a year between October 2020 and July 2024, citing part of the reason as being “property development at the College of North West London [CNWL]”.

The group initially made plans to sell off its campuses in Willesden and Wembley and build a new college in Wembley Park shortly after it formed in a merger between CNWL and City of Westminster College in 2017.

But the plans, which involved demolishing the Willesden campus to build over 1,600 homes, did not get planning approval until December 2024. When FE Week called last week, the campus was still accepting enrolments for students this year. We were told the new site would not be completed until at least 2029.

“The design, planning and approval process for a project of this scale is necessarily complex and lengthy, with the construction phase now scheduled to begin in quarter three of academic year 2025/26,” the group said in a statement.

The group was rated as ‘requires improvement’ during the entire period their chair was being paid, although it was upgraded to ‘good’ in December 2024

When Croydon College was under intervention after being found ‘inadequate’ in 2023, it was “mandated” a chair – former DfE director Valvona – who was paid £350 a day on the basis of working one day a week.

He led a turnaround strategy that saw the college move to ‘good’ in October 2024. But the college decided not to seek approval to continue paying their chair, despite having to go out to recruitment twice before appointing current chair Val Shawcross.

Similarly, Hull College renumerated Lesley Davies, its DfE-appointed chair of goverors, £28,416 from January 2021 to August 2022 when it was under intervention, but its current chair, Rob Lawson, is not renumerated.

Valvona believes that, if a college is coming out of government intervention and no longer pays a chair, this “sends a signal to the person coming in, which is, ‘we’re not really expecting you to operate in the same way as your predecessor’”.

Giving something back?

West Nottinghamshire College was in dire need of a governance overhaul in January 2019 after being rocked by an expenses scandal and forced to accept a £2.1 million ESFA bailout.

The college paid its chair, experienced business executive Sean Lyons, £60,000 over four years to work on a turnaround plan.

Lyons has just received an honorary doctorate from Nottingham Trent University for the work he did with the college, and for work he has undertaken as group chair of Hull University Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust and Northern Lincolnshire and Goole NHS Trust.

He said he would not have accepted the college role had it not been remunerated.

“You’re more likely to attract the right experience if you are prepared to [pay], because these things don’t go without personal risk and reputation risk.”

He believes that, as well as remunerating the corporation chair, it should be “entirely reasonable” to pay the chairs of sub-committees, including the audit, finance and performance committees.

He would expect kickback from “mandarins” to this idea, anticipating “a whole cascade of knock-on effects”, but believes it is “naïve” to think that “public service should mean doing everything pro bono”.

“I hate the phrase, ‘giving something back’. It’s not what motivates me. What drives me is problems that need to be solved.”

How much pay?

FE Week’s FOI revealed chairs post-Covid being paid between £10,000 and £25,000 a year, with the top amount paid by EKC Group to their chair, management consultant Charles Buchanon and MidKent College to its former chair Martin Cook.

LTE Group of education and skills providers (which includes The Manchester College and UCEN Manchester) last year paid its 11 governors £51,453 and eight co-optees £21,548, not including expenses, although it is unclear how much each was paid individually.

In comparison, Skills England remunerates its board members up to £15,000 a year for a time commitment of 20 days a year.

Scottish colleges can pay their chairs up to a maximum amount set by Scottish ministers of £27,560.

Lyons sees the amount he was paid (£12,000 a year) as “a pittance”, and “pitiful in comparison to the turnover of most colleges”. But it was important for him out of “principle, more than anything else”.

In comparison, his other employer, Hull NHS Trust, spent £212,000 on remunerating its non-executive directors in 2022-23.

Lyons is “pretty sure” he could pick up other remunerated chair roles. “So why would I consider a chair job in a further education college with all the risks around that, without remuneration?”

Chair recruitment challenges

Valvona believes that chair remuneration “generates a more competitive market”, attracting “different ages and diverse backgrounds”.

South Essex College explained that it has been paying its chair (former Activate Learning CEO Dame Sally Dicketts) £20,000 a year since September 2024, after “an unremunerated role hindered recruitment in the past”.

And, following the failure of South Hampshire College Group’s recruitment campaign last year, the FE commissioner agreed to “support” SHCG’s payment request.

Last month it started paying former government director of skills Stephen Marston £15,050 a year for a three-year term.

Its CEO Andrew Kaye said Marston’s appointment means that SHCG is now “very well-placed” to respond to the government’s industrial strategy, Skills England’s recommendations and “any implications arising from a new post-16 education and skills strategy”.

SHCG also put the payments down to “recognition of the size and scale of the role for a merged college group”.

Loughborough College has been paying its chair since 2021-22 and officially merged with SMB Group this year, forming Loughborough College Group.

Current chair Stephen Smith is paid £12,000 a year due to “the need to steer the organisation through the anticipated merger process, and historic difficulties in recruiting a chair,” the college said.

Valvona believes that paying chairs means that, when “failure” does happen, “the government can hold people to account because they are paid”. It also becomes “easier to ask [them] to stand down”.

But governance professional Perry Perrot, who is external verifier for the Institute of Directors’ governance qualifications, warned that “payment alone does not guarantee quality or integrity”. He believes “there is a risk of creating a race to the bottom, where remuneration becomes subjective and potentially inflated”.

“Boards should have the flexibility to offer controlled and transparent rewards where retention of high-quality leadership is essential, but this must be underpinned by robust safeguards.”

These safeguards should include “clear KPIs, annual 360-degree reviews, term limits and oversight by an independent audit committee”.

Are some of the people on here doing it for the right reason. A number seem to be ex DfE. If not careful could look like self interest.