Raising the age to which children must participate in school, college or training to 18 has seen “limited impact” ten years after implementation, a study suggests.

But researchers have said the policy of raising the participation age (RPA) has “untapped potential to expand learning opportunities for young people”, and called for “duties and responsibilities” for the policy to be re-assessed.

The participation age was raised from 16 to 17 in 2013 and then to 18 in 2015, in a bid to tackle the fact 10.3 per cent of 16 to 18-year-olds at the time were not in education, employment or training (NEET).

The RPA was introduced after the 2008 education and skills act included provisions for all children to stay in education or training for longer.

Now a report by the University of Bath, FFT Education Datalab, Institute of Policy Research and the Edge Foundation has found an overall reduction in sustained participation among 16 to 18 year olds. Data also shows an increase in the NEET rate.

‘Hasty’ implementation

The idea of raising the compulsory age was to improve teenagers’ “qualification attainment and acquisition of skills, as well as their future employment and earning potential”.

But implementation of the policy was “hasty”, the report found, as it was “delivered in a climate of economic austerity, a change in government, and accompanied change to education management” within local authorities.

The IRP studied data covering all pupils in England state schools in the years immediately before and after the policy was implemented. They also looked at case studies of local authorities Blackpool, Bristol, Norfolk, Sunderland, Wandsworth and Worcestershire.

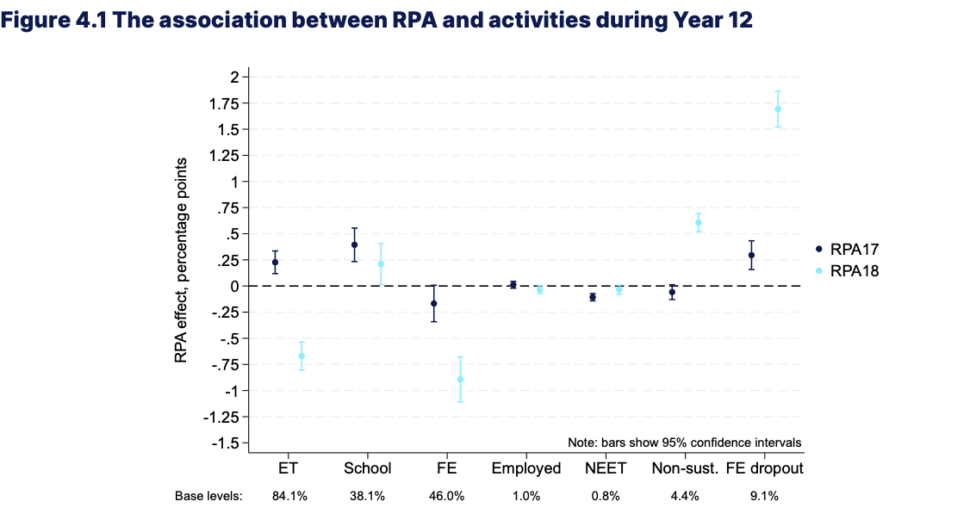

Data showed the RPA was not associated with large changes.

While there was some initial improvement in participation for year 12s and 13s, there was also an increase in mid-year dropouts. The sustained participation rate reduced by around 2 percentage points compared with cohorts unaffected by the RPA.

Boys drove the increase in overall participation in year 12. Girls had a larger reduction in FE participation, while participation among black students reduced much more than other groups.

“We find there was a limited impact of the policy on overall participation in education or training during the first two years post-16,” said Datalab’s Dave Thomson and the IPR’s Matt Dickson in a blog post.

‘Untapped potential’

Young people are met with structural, institutional, social and personal barriers which prevent their participation, the report warned.

In particular, cuts to local authority budgets means they struggle to deliver their RPA duties, with timely reporting of student dropouts “lacking”.

Careers education is “inconsistent in quality, with non-academic routes unevenly covered”, researchers added.

Thomson and Dickson said the research “at times presents a bleak picture but we do finish with a cautious note of optimism.

“We see the RPA policy as having untapped potential to expand learning opportunities for young people, and with that in mind, offer a series of recommendations to find ways of offering earlier intervention during the post-16 phase.”

The report calls for duties and responsibilities of the RPA to be reassessed, with much closer alignment between the Department for Education and Department for Work and Pensions needed.

Other recommendations included equipping LAs with better resources to fulfil their duties, commissioning an assessment of the post-16 maths and English resit model and introducing attendance performance measures.

The RPA legislation was proposed in 2007.and passed by Parliament next summer just as the 2008 financial crisis was taking hold. The Coalition government’s decisions in 2010 to reduce the local authority role in education, cut course funding by 10% (implemented over 4 years) and end Education Maintenance Allowances hollowed out the RPA policy and contributed to a situation where participation rates didn’t rise after 2013 in the way intended back in 2007. It’s odd for the researchers to say this was a failure of RPA. An alternative way of describing the situation is that the policy was never properly tried. As a result of the 2010 changes, the RPA legislation was like an property developer banners disguising an empty building site . A decade later, there’s a new emphasis from new ministers.on a youth guarantee, rising numbers staying in education after 16 and, as the researchers say, a chance for a rethink.