Zamzam Ibrahim took over at the National Union of Students in turbulent times. But the new president is far from a stereotypical drum-banging student leader

Zamzam Ibrahim is burning the candle at both ends and illness forces her to cancel our first interview. But she valiantly battles through by phone from a London café a few days later – with the background noise and a crackly phone line doing little to dim her character and conviction in a startling 50-minute conversation.

It’s been a turbulent time for the National Union of Students, which Ibrahim has led since April. Faced with the union’s looming £3 million deficit, Shakira Martin, the former president, wrote a Facebook post saying she didn’t give “two s**ts” about local unions critical of her cost-cutting decisions and they could “f**k off” (the post has since been deleted). Martin had taken over from Malia Bouattia, who left after calling her university a “Zionist outpost”. Both women were dogged by racist and sexist abuse on social media during their terms in office, Ibrahim watching it all during five years at the union, most recently as vice-president of society and citizenship. Further education needs all the champions it can get, so have students chosen the right leader to navigate the choppy political waters?

“We need to do much more about access to courses”

As we move through my questions, it seems they may have made a shrewd choice. I start off lightly, asking what her priorities are.

“We need to re-think education – the way we talk about education and the ability of students to progress into different schemes, to train and re-train. The way we access further education has been the same for a very long time. There aren’t that many provisions available. So we need to do much more about access to courses.”

For this reason she supports a national education service with its emphasis on lifelong learning. Her own experiences of post-16 education in Bolton have also made Ibrahim an advocate for parity of esteem of FE colleges with sixth forms. “Where I lived if you passed your GCSEs you went to the sixth-form college, like I did. If you failed your GCSEs, you went to Bolton College. They were next door to each other, but if you went to one it was like you’d failed. There’s this cultural shame around some FE. That needs to change.”

Ibrahim is also determined to take politicians to task over FE funding. “The budget has been hugely cut over years, but the expectation of a ‘world-class service’ hasn’t gone away. They’re on a shoestring budget. It’s ridiculous.” Also in her line of fire, as it was for her predecessor, is the removal of the education maintenance allowance by the coalition government in 2010. I ask her if she had needed it. “Honestly, the difference EMA made to me when I was at college! It was £30 a week and it paid for my travel. But I would walk if the weather was all right, so then I could eat. To think that option isn’t available anymore is terrifying.”

It becomes clear that Ibrahim has identified her priorities as things she wants to improve, not lingering for a moment on what she hates or what she wants to do to The NUS. This, it turns out, is a deliberate strategy.

It becomes clear that Ibrahim has identified her priorities as things she wants to improve, not lingering for a moment on what she hates or what she wants to do to The NUS. This, it turns out, is a deliberate strategy.

“The reason I ran for president is I was thinking, ‘why aren’t we campaigning for things like better education and more funding?’ We were spending so much time saying, ‘this shouldn’t happen’, we were fighting things all the time and not offering a vision.”

She does not say that too much time was spent in-fighting, but she could. “We’d stopped being about what was important, and it was more what we were against.”

Even when I ask her how she’s going to campaign for all these changes with a much-reduced budget, she manages to keep things positive and praise her membership. “It’s going to be a balancing act. We might have to go back to being a grassroots organisation. But we have 550 student unions, so we can have huge impact without having to move too much money around. Yes, I’m the face of the organisation. But it’s the unions doing the work. They’re incredible.”

“We were fighting all the time and not offering a vision”

This determined, upbeat approach is working. Ibrahim has been in No 10 and says conversations with Chris Skidmore, the higher education minister, have been particularly good. She says he supported her when she pulled out of the Conservative Party conference about a month ago. Reports had emerged that a panel debate hosted by Policy Exchange on September 29 called Challenging “Islamophobia” included jokes and a lack of proper engagement with the issue (as the title rather gives away). When she withdrew she says Skidmore said he “understood and respected” her decision. It’s all about carefully deciding where to draw a line, she tells me.

“I’m always willing to stand up and fight the case. But sometimes I think it comes down to the principles of the NUS and what we stand for. These people were making jokes at our very life experiences. For me, it was ‘what are the lines here?’ I got solidarity from all the students.”

Where has she learnt to balance passion with perspective? The answer becomes clear, and, at times, desperately moving.

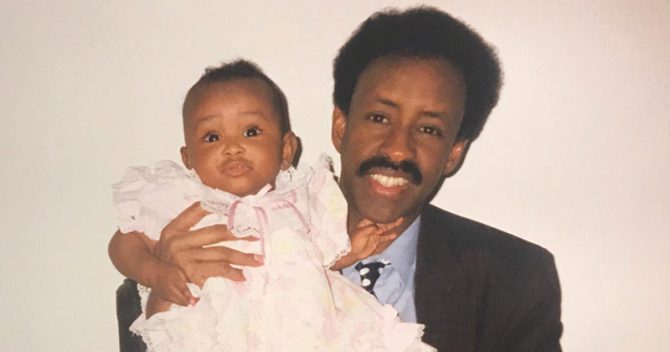

“Coming from a working-class background, and my parents being migrants, they taught us education was everything.” Ibrahim was born in Sweden to a Somali family, with four brothers and a sister; her parents moved to England when she was in year 5. “My mother taught me resilience. Whenever I came to her with a problem, she said, ‘what’s your solution?’ And my dad was the biggest advocate of education I’ve ever known in my life. He said ‘your knowledge is the only thing they can’t take away from you. If you want to get anywhere in life, you have to educate yourself. If there are issues, you need to be in that room’.” Admiration creeps into Ibrahim’s voice. I tell her that it sounds like her dad is an important person to her. There is a long pause and it takes me a moment to realise she’s holding herself together.

“My dad passed away two months ago. He was such a champion for learning. When I was being taught English as a kid, there was a refugee family near by, and he would make me go and teach them what I had learnt. What’s a noun, what’s an adjective, what’s an adverb. His thing on education was, ‘pass it on’. I remember when I started college he’d say to me, ‘tell me what you’re learning in science’. When I was studying for my GCSEs, I bought revision CDs for all my subjects. My dad spent all night making copies of them and he gave them out free to all the people who couldn’t afford them. For him it was about, give back to the person who doesn’t have what you have. Even when we had so little, I was constantly reminded we had so much.

“He knew what I was doing with the NUS. The last time I saw him, I was running for president. He would always call me and say, what part of the world are you in today? He would google me and send me anything with my name in case I hadn’t seen it.”

Ibrahim’s parents appear to have nurtured in their daughter a passion for change that comes not just from indignation, but humility too. It strikes me as a promising recipe for leadership.

“After my dad passed away, it came back to me again and again about education.

“Yes I’ve had institutional barriers, but I have got here. Now I have a lot of work to do to help people who think they can’t.”

Your thoughts