Ali Hadawi left FE for business. But as the principal of Central Bedfordshire College tells Jess Staufenberg, something just didn’t feel right

Ali Hadawi tried to leave teaching once. It didn’t go well.

He was in his third job in FE after starting off as a lecturer at Sheffield Polytechnic (as it was then) during his PhD before moving to Peter Symonds College in Winchester as a computing lecturer. At 30 he became head of computing at Barton Peveril College in Hampshire. “That was my first go at management. But after a few years, I had at the back of my mind that education wasn’t really my destiny. I wanted to be out there in industry as a computing engineer. So I went to see the principal . . .”

And therein lies a story.

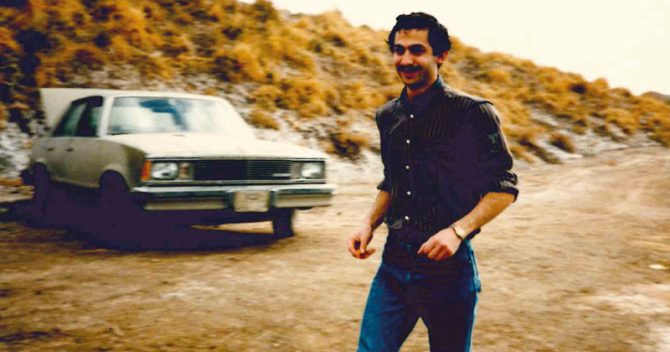

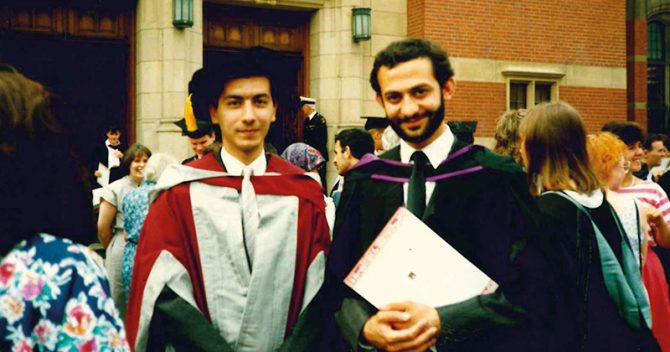

Things were going well for Hadawi, who had left Iraq to study briefly in the UK, but were already far from the original plan. Arriving in England at 18 and unable to understand English well, he had been expected home by his father within a few years. In his new language, he gained A levels at what is now South Gloucestershire and Stroud College in pure maths, further maths, statistics and physics. Then he won funding for a doctorate at Sheffield Polytechnic, now Sheffield Hallam University, in artificial intelligence neural networks.

“That was the point when my dad wanted me to go back. My argument was I’ve got this fantastic scholarship, can I finish that? And he thought, yes, why not.” But circumstances again forced Hadawi’s hand as, back at home, Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait, triggering the start of the Gulf War in 1991. Despite a “magical” childhood, Hadawi says, “it wasn’t wise to go back. It wasn’t safe.”

So there he was, 30 and a head of department in FE in England, and wondering if he’d made a mistake. Colleges had never been the plan. “Education wasn’t on my radar as my career growing up. My father is a businessman. My two older brothers are engineers.” He has four sisters, one of them a senior banker. Teaching was not in the blood. So he quit.

After all these years, Hadawi says he’s never forgotten the conversation with his principal, Godfrey Glynn. “I went in to see him and explained that my aspiration in life was not to be in education, but in industry. And he said, ‘that’s a big jump, why don’t you go away for a month and think about it’. So I did, and I came back and said ‘no, I’m determined’. He said he’d give me a year’s leave without replacing me, and after that I could write to him to say if I wanted to stay in industry. He removed all the risk for me. He was a great man. I’ve never forgotten it.”

Hadawi wrote to Glynn after a year to say he wanted to continue as a computer engineer. But slowly, despite the better pay, something didn’t feel right.

“By 2002, it just dawned on me that I wasn’t really enjoying what I was doing. I was working across London, Dubai and Oman, and the technical aspect was interesting, but at the end of a project, I just didn’t have that ‘yes’ moment. I missed the bit with students where their eyes light up.”

I missed the bit with students where their eyes light up

Had Glynn anticipated this? Hadawi considers this. “Yes, indeed. Perhaps.”

He began searching for jobs in FE. Why FE over schools? There is no hesitation. “There’s something about FE. In FE you’ve got a lot of students who might not have the self-esteem or the right level of challenge and support at home. It’s the age group I want to work with.” He’s also clear about the special expertise of staff in FE. “There’s the aspect of dual professionalism. If you’re teaching mechanics, you’re a motor mechanic and a teacher. So that helped me a great deal, because I’d worked in industry and respected that.”

In his next role at Greenwich Community College he improved the Ofsted grade for the maths, science and technology department from ‘inadequate’ to high progress. By 37 he was vice-principal. He then spent five years as principal at Southend Adult Community College, galvanising a “demoralised” staff. “It got me really interested in the whole notion of people motivation and leadership.”

In 2011, he became principal of Central Bedfordshire College. The same year, he received a CBE for his services to FE and for the successful partnership work he had done with FE colleges in Iraq. He was here to stay.

Hadawi is one of the calmest, most concise interviewees I’ve met. When we reach the point in his story where the college, having been graded ‘good’ twice, dropped to ‘requires improvement’ in 2018, I have rarely heard such a sanguine, scientific response from an education leader.

“I thought I’d be safe to experiment, and naturally with an experiment things don’t always work.” What was he trying to do? “We had built a system in the college in which everyone had to conform, with 100 per cent compliance. So if you’re a poor quality teacher, it raises you up to good. But if you’re a brilliant teacher, it dumbs your work because you can’t be creative.”

Hadawi wanted to give all teachers more autonomy, so he reduced the requirements for lesson plans and student reviews. “It was right to loosen out these requirements. The mistake was to treat everyone with the same level of autonomy. We were still convinced about what we were doing and hadn’t picked up the signals in some areas it wasn’t working so well.”

Like any good scientist, Hadawi has turned to research to get the college back on track. His main blueprint is The role of leadership in prioritising and improving the quality of teaching and learning in further education, a report by Professor Matt O’Leary at Birmingham City University. It discusses “structured autonomy” – exactly the tricky balance Hadawi wants for his college, and, indeed, FE as a whole.

As well as an ability to focus on small areas for improvement in telescopic detail, Hadawi can step back and look at the stars. I ask what FE needs. “Two things. The first is a properly formed sector voice – it doesn’t exist. It means that while we usually agree with policymakers’ intentions, the sector voice isn’t there helping decide how to do it.”

We don’t tap into research to inform our practice

Isn’t that the Association of Colleges? “They are a voice in the sector. They’ve done particularly well on funding. But when we had T-levels, institutes of technology, university technical colleges, where was the sector voice in actually creating that policy? The sector never really said, that’s how it should be done. We react once the policy is decided.”

But Hadawi doesn’t think any idea from the sector is de facto good.

“The second thing is research evidence. The issue is not just with policymakers, it’s with FE itself. Though there is this big body of research out there, we don’t tap into it to inform our practice. It’s not because we’re too busy, it’s because we’re not used to it. So we need to have a proper sector voice, backed by research evidence, to take to policymakers.”

He points me to four places with a “great repository” of evidence on FE: the Association for Research in Post Compulsory Education, the British Educational Research Association, the Education and Training Foundation and the Learning and Skills Research Network.

“You should set something up,” I say.

Hadawi laughs. “When I retire.”

For now, this scientist and leader has work to do. Thank goodness he stayed in the sector.

Your thoughts