The Greater London Authority has so far drafted in 57 new bureaucrats to handle the capital’s adult education budget ahead of devolution next year.

Fifteen posts in various other teams are still to be appointed and will eventually bring the total number of administrators in the department to 72, the majority of which will eventually and controversially be paid for via a top-slice of £3 million from the adult skills budget.

An organogram of the authority’s new AEB structure was published in a briefing document ahead of a GLA meeting about the budget later this month.

The physical image (see below) lays bare the scale of the team being employed, which sector leaders have criticised as mayor Sadiq Khan plans to fund their wages by using less than one per cent of the capital’s £311 million annual AEB cash, diverting it away from frontline learning.

Employees in the AEB team are currently funded either by the GLA or externally.

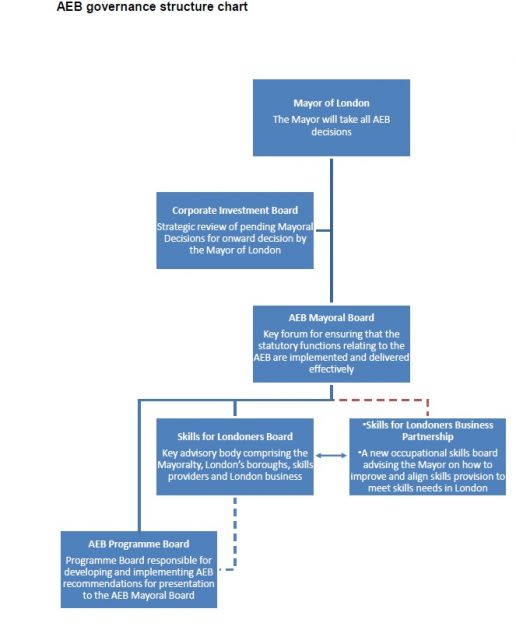

On top of these posts, the briefing document outlines the GLA’s vast AEB governance structure (see image below), which will include a corporate investment board, AEB mayor board, skills for Londoners board, and an AEB programme board.

It comes ahead of a big month for AEB planning in London, as the inaugural meetings of the skills for Londoners and mayoral boards are set to take place, as well as appointments to the London occupational skills board.

Members of the AEB mayor board include Mr Khan, the deputy mayor for planning, regeneration and skills Jules Pipe, the mayor’s chief of staff David Bellamy, the mayoral director for policy Nick Bowes, and the GLA’s executive director of resources Martin Clarke.

Appointments to the Skills for Londoners Board are currently being finalised but are expected to be published before their first meeting on September 21.

The team of 72 AEB officials will form six units: a strategy, policy & stakeholder relationships team, a co-financing organisation to handle the European Social Fund, a funding policy and systems team, two programme delivery teams, and a management team.

Principals at a couple of the capital’s largest colleges have blasted the prospect of diverting adult education cash away from the classroom into the hands of administrators – although the GLA insists the blame lies with the government’s unwillingness to pay for what it sees as necessary oversight.

“Shocking and hugely disappointing that this has been allowed to happen and divert £3 million from this underfunded sector to pay for administrative officers @MayorofLondon #accountability #valueformoney #skillsforlife ultimately hurting learners the most,” Sam Parrett, the principal of London South East Colleges, tweeted at the time.

FE Week then revealed in June that the new AEB department will also be used to lobby for control of 16-to-18 funding, which drew further criticism.

“There are some 457,000 Londoners without qualifications and thousands more with health issues and older learners,” said Naina Kent, the equality representative for the University and Colleges Union’s London regional committee.

“That is what the budget is there for, and not on creating policy for those learners who are supported by other funding streams.”