Ofsted’s chief inspector was quizzed by FE Week’s chief reporter, Billy Camden, on a selection of topical questions at the Association of Colleges’ annual conference

College finances – should they feature in the leadership and management judgment?

Several college leaders and boards have come under heavy criticism from the FE commissioner for their management of the finances.

So why doesn’t the education watchdog take into account financial management during its inspections? To find out, FE Week asked the chief inspector, Amanda Spielman.

“I think it’s very clear that our responsibilities are mainly about quality, and theirs [the FE commissioner’s team] are mainly about finance,” she said.

“We don’t have the remit to look at that side of colleges, and that’s something that’s down to the Department for Education to decide if it wants to shift the split. But it is important. They affect each other clearly. Neither we nor anyone else should say they’re completely independent of each other.”

Asked if Ofsted inspectors may take a closer look at college finances future common inspection frameworks (CIF), particularly around the leadership judgment in reports, Ms Spielman didn’t rule it out.

“There are a lot of different ways that you could cut this particular cake,” she explained.

“If a conversation begins at some point about ways of taking that forward I’d be happy to have it. At the moment we’re developing our framework on the basis that the responsibility is where it is at the moment.”

Campus-level inspections – will they happen?

Campus-level inspections are also not going to feature in the upcoming CIF, Ms Spielman confirmed.

Ofsted previously said that if “more granulated performance data” was available it would be open to performing the inspections, which are being called for by large college groups such as NCG.

But the chief inspector ruled out introducing them in the upcoming CIF, being launched in September 2019.

“It’s still very much on the list of things we’d like to do but looking at the logistics, looking at when the data, the campus-level data that’s needed to do it is going to become fully available, it just doesn’t fit with the timing of this framework,” she explained.

“There’s no point in trying to consult on a proposition now. It’s something we’ll have to do down the line.”

How many is too many grade-three reports for one provider?

Earlier this week, high street giant Boots was hit with a third ‘requires improvement’ rating in a row. Before Ms Spielman’s time at the helm of Ofsted there was a rule which said three grade-three reports in a row for a provider would equal an ‘inadequate’.

But the current chief inspector wasn’t a fan of it.

“I changed that rule very shortly after I came in because I thought it was flawed in conception,” she said.

“The job of inspection is to report on what we see when we inspect. Notwithstanding that something may still be at ‘requires improvement’ level, that does not of itself say right, really what we inspected was ‘requires improvement’ but we’re going to say it’s ‘inadequate’ because we saw ‘requires improvement’.

“To artificially say that something is ‘inadequate’ and trigger all the consequences that we know go with grade-four judgments, because we want to heap up pressure, I don’t think that’s the right thing for us to do”.

Asked if she would give a provider five grade-three reports in a row, for example, she said it would be “interesting to see what conclusion that took us to on governance if we got to something that looked like a fifth ‘requires improvement’”.

Tick-box apprenticeships, is Ofsted still worried?

The inspectorate’s deputy director for FE and skills, Paul Joyce, raised concerns in May that the quality of apprenticeships is in decline, and the programmes are starting to resemble the doomed Train to Gain initiative.

Is this a concern that Ms Spielman shares, currently?

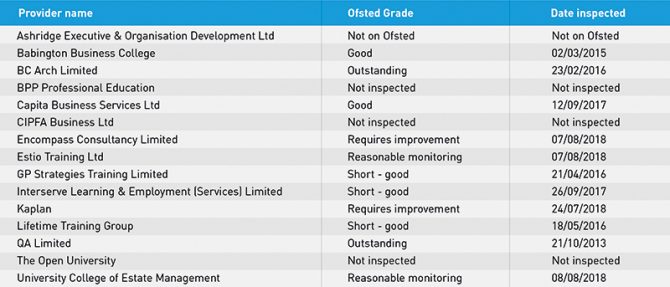

“We have started monitoring visits to all the levy-funded apprenticeship providers because I was really concerned about opening that up to a raft of new providers and leaving them for several years without scrutiny,” she said.

“We’ve done well over 100 visits so far and happily the majority of them are doing what they’re doing, but there’s a significant portion of them that aren’t making sufficient progress, where there is reason to be concerned.”

She continued: “I think everybody wants to see the apprenticeship reforms to do well, and to have a flow of excellent high-quality apprenticeships and training, and part of doing that is weeding out the stuff that shouldn’t be there as quickly as possible before it messes up any individual’s life too much.

“Getting to the end of an apprenticeship and discovering that you haven’t actually had what you were supposed to have and that what you’ve got has got zero labour-market value is not a great place to be. I don’t want that to happen to learners.”

Will Ofsted urge Treasury to increase FE funding

Ms Spielman has long said that the base rate for 16-to-18 education needs to be boosted.

She reiterated this view last month in a letter to the Public Accounts Committee but revealed for the first time that inspections are now finding that a lack of cash has directly led to falling standards in FE.

Asked what Ofsted could do to get the Treasury to invest, the chief inspector said: “I think the main thing I can do is to talk honestly about what we see and what I do is to try and speak about the things that I think really need attention rather than absolutely everything under the sun.

“I think you have more impact if you really go for the things that matter.”