Millions in apprenticeship provider “failure” write-offs, the skills minister’s salary and payouts to senior officials all feature in the Department for Education’s accounts this year.

The department’s annual report for 2024-25 was published this morning, as were the Education and Skills Funding Agency’s final accounts following its merger with the DfE in March.

Here’s what we learned…

Hefty cash losses from apprenticeship ‘failures’

The department suffered £24 million in losses and claims that were waived or abandoned in more than one thousand cases that were not linked to student loans.

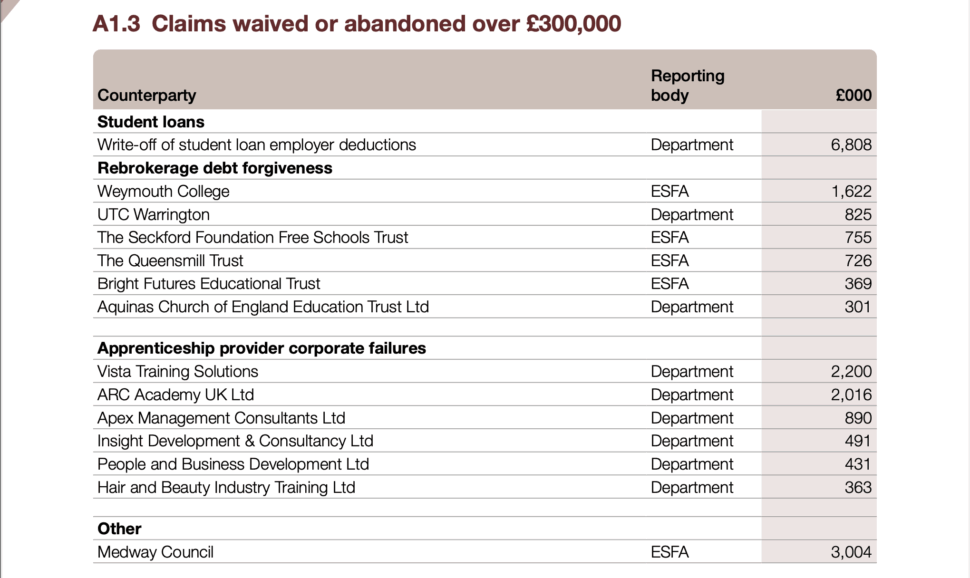

Several apprenticeship providers and one college were named individually where the value of the written off funding clawback by the government hit over £300,000.

This included Vocational Skills Solutions, which closed down in 2023 and left the taxpayer £633,000 out of pocket.

Debts totalling £6.6 million were written off after the “corporate failures” of six apprenticeship providers: Vista Training Solutions, ARC Academy UK, Apex Management Consultants, Insight Development & Consultancy, People and Business Development, and Hair and Beauty Industry Training.

Vista Training Solutions cost the DfE £2.2 million. The company’s director, Shakar Habib has since received a six-year ban, as reported by FE Week in January 2024.

The department also waived £2.016 million owed by ARC Academy UK Ltd, which was judged ‘inadequate’ by Ofsted before closing.

The remaining providers had less than £1 million waived.

Most debts related to “overstated funding claims” that the DfE seeks to reclaim where possible, “but in some cases the provider has failed”, the report said.

The department also recorded a loss of £510,000 to Lambeth College this year, which merged with London South Bank University in 2019.

Meanwhile, £1.6 million was also written off for Weymouth College, which merged with Kingston Maurward College in 2024.

And UTC Warrington also had £825,000 written off for un unspecified reason.

Smith’s salary revealed

The department paid skills minister Jacqui Smith an £86,804 basic salary in the 2024-25 financial year after she started part way through the financial year in July, equivalent to an annual salary of £117,851.

This is a higher yearly wage than education secretary Bridget Phillipson’s £67,505, although Phillipson also receives an MP’s salary of equivalent to £91,346.

As a member of the House of Lords, Smith does not receive a salary and has never claimed a £342 daily attendance allowance, according to latest data that goes up to February, although she claimed £800 in secretarial expenses in September last year.

Bumper pay rise for top boss…

DfE permanent secretary Susan Acland-Hood saw her salary band rise to between £180,000 and £185,000 pounds last year, up from between £170,000 and £175,000. Her pension benefits also increased from £108,000 to £137,000.

It means her pay and benefits rose by 12.3 per cent, compared to a DfE staff average of 5.2 per cent.

…and big increase in exit packages

The DfE and its agencies and arms-length bodies paid out £3.9 million in exit packages to 64 departing staff in 2024-25. In 2023-24, it had paid £1.27 million to 30 people.

Two of the exit packages last year were worth between £150,000 and £200,000, while six were between £100,000 and £150,000.

Exit packages are for staff who are made redundant or retire early. It does not name which staff the payments relate to.

The DfE also sometimes makes special “severance payments” when employees or contractors resign, are dismissed or reach an agreed termination of contract.

In 2024-25, it made 23 payments totalling £1.3 million up from two payments totalling £115,000 in the year prior.

The highest payment was £142,186.

£17k payout for Keegan

Ministers get severance payments when they leave office, regardless of whether they resign, are sacked or voted out as MPs.

The report shows former education secretary Gillian Keegan received £16,876 last year after losing her seat, while departing schools minister Damian Hinds and skills minister Luke Hall got £7,920. Former children’s minister David Johnston received £5,593.

The document also shows £7,920 was also paid out to Nick Gibb and Robert Halfon, who both resigned as ministers in late 2023.

£234k to Keegan’s husband company, £21k to Smith’s consultancy

It’s not just axed ministers getting pay days.

The report details related-party transactions, spends by the DfE with organisations linked to ministers and board members.

It shows £234,000 was spent with Centerprise International Holdings Limited, an IT provider of which former education secretary Gillian Keegan’s husband is a non-executive director.

Meanwhile, £21,000 was paid during the year to Jacqui Smith Advisory Ltd, a company owned by the current skills minister Baroness Smith. And £14,000 went to Steve Crocker Consultancy Ltd, run by DfE board member Steve Crocker.

The accounts do not state what the payments are for but a government spokesperson told FE Week the extra payment to Smith relates to her time as the DfE-funded independent chair of Sandwell Children’s Trust, which she stepped down from before joining government.

Fraud and audit

The ESFA’s counter-fraud team claims to have detected £20 million in fraud and prevented a further £71 million being paid out, from the £79 billion in public funds it distributed.

During the year it recovered £10 million, which includes amounts from cases in previous years.

It also carried out funding audits of 79 FE colleges and 91 independent training providers, although it did not specify how much funding was clawed back.

The number of new allegations the counter-fraud team handled increased from 142 to 246 in 2024-25, with 118 cases relating to ITPs and 41 to colleges.

However, more than 200 of these allegations did not proceed to a formal investigation as they did not meet the threshold, were referred to other bodies, or concluded with “advice” to colleagues.

Contrary to its own policy, the ESFA has only published two reports detailing counter-fraud investigations, despite carrying out nearly 200 full investigations between 2017 and 2024.

But the DfE’s annual report says merging with the ESFA will “ensure a more cohesive approach” to investigations, positioning it “at the forefront of counter-fraud efforts across government”.

£13.6m Ecctis repayment

The DfE’s counter-fraud team, separate to the ESFA’s, secured a £13.6 million repayment from its contractor Ecctis, which runs the UK’s official agency for recognising international qualifications and running language tests.

Earlier this year, permanent secretary Susan Acland-Hood said a “very hard” review of Ecctis found that the company had failed to reinvest profits from the not-for-profit contract back into the service as promised.

The accounts say the department has now “strengthened” contractual management arrangements.

Loans rise

The DfE’s total amount loaned to FE providers increased from £170 million to £256 million.

It lent a total of £103 million during the year and received £44 million in repayments.

Following public sector reclassification the DfE has faced growing demand for financing from colleges, which have lost the freedom to take out commercial loans in most cases.

During the year nine colleges received £25 million in emergency funding or loans, which the DfE says protected 61,000 learners.

A further £91 million was loaned to 24 providers, most of which were FE colleges, according to the accounts.

£600m ‘irregular’ grant spend identified by auditor

The DfE paid out £88.3 billion in resource grants and £5.5 billion in capital grants in 2024-25.

Gareth Davies, the comptroller and auditor general to the House of Commons, said he identified irregular grant spend in several areas.

Within the core department, he identified estimated irregular grant spend of £61 million relating to various grant streams.

“I also identified an estimated £588 million of irregular spend within ESFA and £63 million of known irregular spend,” he added.

No further details on which grants were irregular and how was provided.