Six weeks after lockdown and the sudden end of inspections, and five weeks after Ofsted mooted a mass redeployment of staff, JL Dutaut finds out what the inspectors have been up to

It’s now six weeks since “business as usual” came to an abrupt end for Ofsted. Yet just last week, chief inspector Amanda Spielman admitted to the education select committee that a “considerable number” of her staff were “less than fully occupied”. Cue rumblings of criticism among the profession. But what is the inspectorate to do when its primary function is deemed inappropriate?

Perhaps better to ask what it is that Ofsted staff and inspectors are doing at this time of national crisis. It is five weeks, after all, since Paul Joyce, its deputy director for further education and skills (FES), said Ofsted was working with the Department for Education to redeploy its staff, including as support providers if needed.

Acknowledging that “under-occupation” is a fact for many, what is it that colleges would like this workforce to be doing? (It’s worth noting, however, that inspections haven’t stopped altogether. They will also resume, which means the organisation has to avoid conflicts of interest, not only now but in the future.)

According to Karen Shepperson, the inspectorate’s director for people and operations, the decision was made early on “to do whatever we could to support the wider government effort, while maintaining our independence on the few emergency inspections we’ve had to do (in the social care space)”.

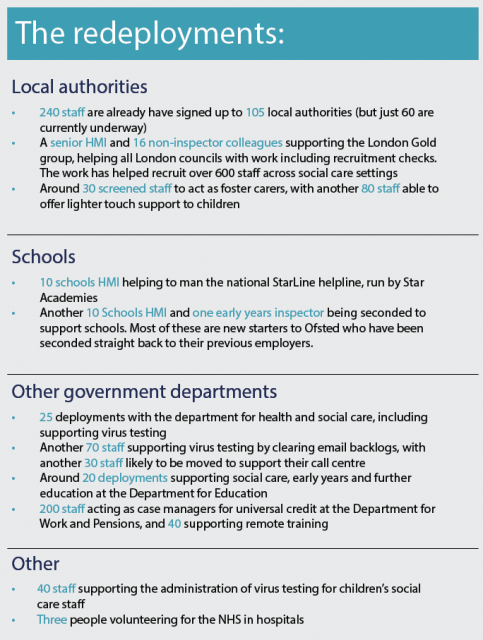

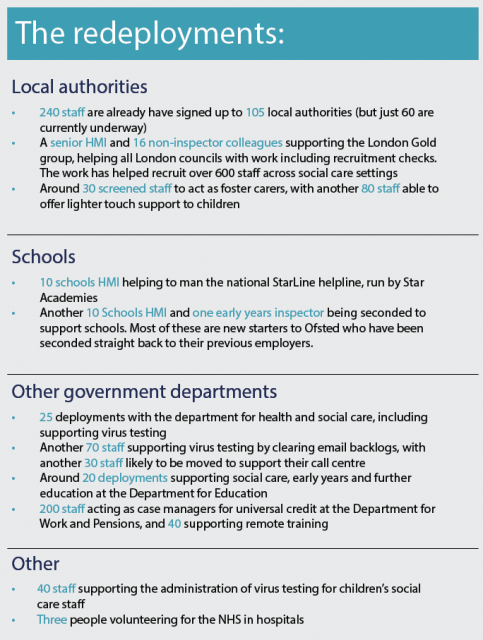

Most redeployment is happening in-house. About a third of Ofsted’s 1,700 staff are “fully occupied with the day job or our own emergency response”, she says. The bulk of the rest, who have been reassigned, are helping other government departments and working through local authorities, who have been tasked by DfE to coordinate local responses. Ninety-five are supporting the Department of Health and Social Care; 240 are supporting the Department of Work and Pensions; 20 are with the DfE. A further 240 are or will soon be supporting 105 local authorities (LAs).

Other redeployments bring the total to some 700 of the 1,200 or so available (see infographic). Of those, few are working in colleges. Ten, for example, are working with Star Academies, but even that work is limited to supporting Starline, a national parent helpline for home learning. About 500 remain “under-occupied”. Why aren’t they in schools and colleges?

As the Facebook relationship status goes, it’s complicated.

As Shepperson says, the DfE directive is for LAs to coordinate local Covid-19 responses. “We have therefore been directing our support mainly through local authorities. If schools and colleges need support they should contact their LA, and if Ofsted can provide that support, then we will.”

But that’s an unusual place for college leaders to look for support and Joyce says most is being coordinated through the Education and Skills Funding Agency (ESFA).

“Our advice . . . is to go to ESFA territorial teams. . . We’ve linked very closely with the ESFA and DfE, so if providers do contact those teams, they will do some triage activity to identify what sort of support providers are likely to need and then if necessary DfE will make that referral to us.”

Some are volunteering as foster carers, and one is making PPE for the NHS

Meanwhile, his team of 80 FES staff are also working with sector associations, including the Association of Colleges (AoC), the Association of Employment and Learning Providers (AELP), the Sixth Form College Association and HOLEX, among others.

Joyce’s own work consists of “arranging some of the redeployment placements, and leading on the policy work we’re doing internally about return to inspections and what that might look like when it when it happens”.

“We’ve also got a range of deployment placements across FE and skills and, as you would expect, they are across civil service departments or in local authorities. Some HMI are volunteering as foster carers, and one HMI has been seconded to an engineering firm to make face masks and PPE for the NHS.”

Next, while leaders like Central Bedfordshire College principal, Ali Hadawi want more Ofsted involvement in colleges and across the sector and believe its inspectors could make positive contribution, it is unclear whether his opinion is widely shared.

And even among those who do want Ofsted involvement, it is not clear there is any consensus as to what that might look like. Hadawi has forthright ideas, but they are by no means guaranteed to be shared by all, and it’s unclear that Ofsted has the expertise and capacity to respond to everyone’s needs.

Although 500 are nominally available for redeployment, the 80-strong FES team are already in the main internally redeployed. Responding to only some could be seen to create an uneven playing field.

However, her explanation that low staff absence and “a very limited” number of pupils lessens “the need for additional people to work in schools and colleges” seems potentially misleading, and it is an interpretation Joyce also offers.

As suggested, it may in fact be that colleges and independent providers are not accessing available support because it is not being offered where they would normally seek for it.

Equally likely, it may be that the relationship between colleges and their inspectorate is such that turning to Ofsted for support is simply no longer a consideration.

As Hadawi says, there might be a need and an opportunity to “reset the relationship between a teacher and an inspector”.

There will always be judgments when Ofsted come to inspect

“There will always be judgments when Ofsted come to inspect,” he says, “but we’ve got experiences in the past where Ofsted didn’t only inspect.” For him, there must be a way through the Covid crisis that “uses Ofsted expertise to help improve the quality of learning that our learners are receiving remotely”.

As well as developing curriculum provision, he is concerned about assessing the quality of teaching. “All we seem to know is to ask teachers to allow us to do an observation of the session remotely. There must be better ways of doing that, and I wonder whether if there was an engagement with Ofsted – not in a judging space, but in a co-creation space – where we could be thinking together about what are the hallmarks of good remote teaching and learning are.”

And while this indicates that there is a general need for support within colleges, there is also sector-wide work that could be put in place for them to tap into, rather than in response to specific requests.

For example, Hadawi thinks Ofsted could use its networks and leverage to ensure the quick spread of best practice, to fill the need to support managers who are having to relearn their jobs from scratch while socially distanced, to create a “safe space for them to share their challenges and anxieties” and to work out what works.

To an extent, some of that work is beginning to happen. Joyce notes that his team has worked and are continuing to work with the DfE sourcing and pulling together free online resources for the Skills Toolkit online learning platform.

What we want to do is to contribute where we have that experience and expertise

In addition, the FES team is collaborating with sector organisations such as the AoC and AELP “to look at some sort of Ofsted evaluation of online learning practice so that we can identify what’s working well and perhaps what doesn’t work as well. But we’re very conscious that this is not going to be inspection activity. This is not going to be grading anything. What we want to do is to contribute where we have that experience and expertise and to get a message out in the sector of what works well.”

As the Covid crisis response changes – with providers set to reopen to progressively larger groups of students over an indeterminate period and a return to routine Ofsted inspections unlikely – there is every chance that this work will develop.

One certainty is that the speed and effectiveness with which it will happen will be in great part determined by the inspectorate’s ability to build trust in its supportive aims and to ensure its staff have the freedom to innovate and to be seen, too, to make mistakes.

The openness with which it has responded to this feature is an encouraging sign. The picture may remain unclear as to precisely what an inspectorate does when it isn’t inspecting, but an inspectorate, after all, is made up of inspectors.

As Shepperson says: “This is the greatest challenge the civil service has faced for a generation at least. Many of our staff redeployed across government are supporting the most vulnerable families. We have had an amazing response from [them].”