FE Week meets the new WorldSkills International president trying to live up to a legacy while negotiating the headwinds of multiple global challenges

Chris Humphries didn’t expect to be in this position. Taking over the presidency and chair of WorldSkills International after the untimely passing away, aged just 57, of its deeply respected and newly-elected president, Jos De Goey in February this year was, he says, “not on my plan”.

Humphries had been elected as an ordinary member of the board. “It was all I expecting to do. Jos was the head of WorldSkills Netherlands for decades, and was everyone’s choice to be the next president. We were delighted when he was approved unopposed by the members and we expected him to serve his full, maximum eight-year term.”

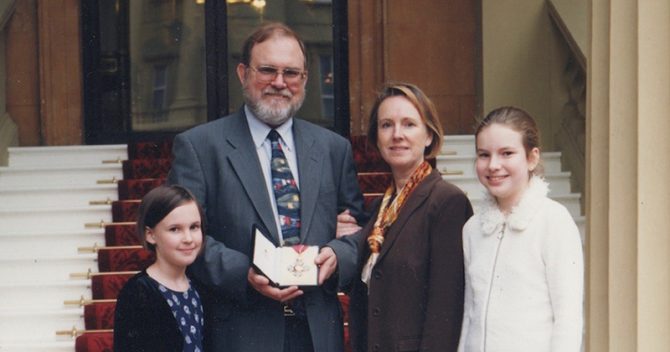

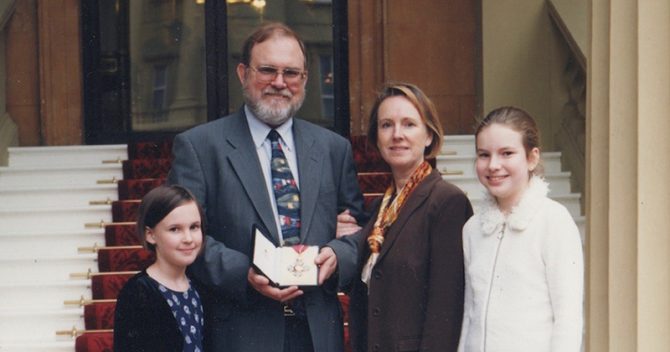

For someone who has spent his entire career in the skills sector, with a somewhat intimidating CV of professional and volunteering positions including leadership in education and industry and driving national strategies, Humphries is self-effacing about his own vision. “I’m doing my very best to make sure that I live up to everyone’s expectations based on what Jos was going to try and bring to WorldSkills.”

That agenda, Humphries explains, “is to exert more positive and beneficial influence on the content and structure, the curricula and the assessment of VET (vocational education and training) systems around the world.” That already sounds like a vast remit, but as if picking up from such a legacy and after such a trauma isn’t hard enough, Humphries has been given the reins at a time of extreme headwinds for a global organisation that aims to foster partnership and to champion young people in industry.

Even before the Covid pandemic, the global political scene was defined by Brexit and by American retrenchment. Unequal development still threatens geopolitical stability. Environmentalism, especially among the youth, was becoming more global and more radical, and we are undergoing a technological revolution – accelerated by the response to Coronavirus – that is transforming precisely the kinds of jobs WorldSkills is built to champion.

It’s quite a cocktail, but Humphries has a knack for disaggregating its ingredients and putting them back together in less threatening admixtures. Perhaps that comes from having been instrumental to the 10-year strategy to take WorldSkills to 2025. He is steeped both in the organisation and the sector, and has had time to gaze into a crystal ball with some of the sector’s leading lights, not just here but around the world.

Did that document get everything right? No. “Of course, the long-term impact of Brexit on Europe wasn’t a feature, but to be honest, that’s been a relatively easy one to track. The UK’s position in WorldSkills Europe has been strongly protected through all of this. And of course, we have no foresight or expectation of the impact of Coronavirus.”

Nevertheless, he says, “we were on target with some of the challenges, in particular sustainability and environmental impact. We were particularly keen to ensure that our competitions are as environmentally sound as possible, and that includes everything from looking at the materials we use to the projects we set.”

The Chinese are determined to open their doors, but will the rest of the world come?

As surprised as he genuinely is to find himself in the presidency of WorldSkills International, it was never a given that Humphries would be involved with skills at all. Yet his study of philosophy at bachelor’s level at the University of New South Wales – a degree he took 7 years to complete – clearly still informs his incisive analysis of today’s situation.

If the degree took him so long, it is in great part because of his politically active youth, which saw him serve as the deputy editor of the university paper and as student union president. It was the end of the sixties and Humphries was, to all intents and purposes, a bit of a campus radical. He later found out that the man his father had named as his godfather was a member of Australia’s intelligence services, and had “a rather large file on him”.

“I couldn’t get into America for a number of years because I’d been too active in the anti-Vietnam war movement,” he adds with what sounds like some relish, and also confesses another reason for his lengthy studies: “I was probably enjoying myself a little too much.”

From Sydney, Humphries came to England to take up a master’s degree at the LSE under Karl Popper, but quickly realised he was done with academia. “I needed a break, and I met someone who was doing this job working in a school around media and working with teachers and children to actually try and change education. I just thought it sounded interesting.” It led to his first job in the UK, in 1974, as a media resources officer at the Inner London Education Authority, helping to effectively apply technology to improve learning.

He started as technician, on the shop floor, and Humphries hasn’t looked back since. He has committed his entire career to the overlap in the Venn diagram where education meets technology, with stints at the National Council for Education Technology, Acorn Computers, Training and Enterprise Councils, City & Guilds and others, and contributed to the evolution of technical education since before Thatcher’s technical and vocational education initiative.

It’s an illustrious career for a man who came from a broken home, and whose childhood was put back on track by his stepmother. His biological mother “disappeared” when Humphries was four, and until the age of twelve he was “fostered out to relatives”. His father had no formal education, but “taught himself and eventually became a state manager for one of the big insurance companies in Sydney.” His stepmother first ran a baby store, then became a bookkeeper of such skill that she was recruited as the treasurer and company secretary for Japanese-run global stationery manufacturer (and inventor of the whiteboard pen!) Pentel in Australia. “Within three years, she was the first female and first non-Japanese director of a Pentel subsidiary in the world.”

His father was no less inspirational. Having worked his way up to a position of some status, he watched his wife overtake him and, at a time when this was still socially awkward, embraced his new role as the ‘directors’ partner’. “He threw himself into it with great gusto and he became a sort of little celebrity in this group of partners, all of whom were Japanese women. They had to adapt all of the partner visits and trips to make sure they could somehow cope with this stray Australian man.”

Good humour and optimism characterise my conversation with Humphries, and he will need them in spades in the first months of his unexpected role. The next WorldSkills global competition is set for Shanghai next year, and the Chinese authorities are determined to open their doors, “but will the rest of the world come?”

With 20 per cent of national competitions cancelled this year, and a further two thirds postponed indefinitely, the challenge is a steep one. But Humphries sees a bigger picture and a bigger role for the WorldSkills network. Seventy per cent of its member countries and regions have closed their colleges and training providers, “so we’re doing a lot of active work around the world to explore how many countries have taken their training online”.

We are looking to establish a potential project on creating a model for hybrid assessment

It’s work that could bring forward the agenda to develop remote assessment of skills in leaps and bounds. “The problem with VET is that it is in the application that the skill is properly reflected. So we are looking to establish a potential project on creating a model for hybrid assessment that would allow not just us but colleges, apprenticeship employers and training providers to conduct validated assessments at a distance.”

Additionally, developing countries are particularly struggling, and increasing the quality of VET there is difficult even in the best of times, so Humphries and WorldSkills International are leveraging member-to-member support to lay the groundwork for leaps forward. “Member cooperation has been driving us for the last two months, and over the next four months, we’ve scheduled a whole series of workshops, seminars, coaching sessions, material exchanges, and the sharing of projects and materials to protect those nations and help them get ahead of the game.”

In passing, he praises WorldSkills UK and its CEO, Neil Bentley-Gockmann for being “a leading light in much of what’s happening here”. But tackling inequality seems to permeate the whole organisation, and none more so than its inadvertent president.

His other role is as pro chancellor of the University of West London – a university set up to serve disadvantaged students and which bills itself as ‘the career university’. (They considered ‘the vocational university’ as an alternative.) Until Humphries joined as part of a shake-up, it was set to fail. It is now among the top 50 in the UK.

“Targeting young people for whom education and higher education is not on their radar and creating opportunities for them is a fantastic agenda.”

It’s an agenda Humphries has been pursuing his whole life, and there’s no doubt this lapsed philosopher and radical will leave a legacy at WorldSkills in his own right.