Colleges and schools have missed two-thirds of their T Level enrolment targets, with digital proving to be the toughest subject to sell to students, according to early findings from an FE Week survey.

But leaders are still celebrating the initial figures, which could increase slightly as recruitment continues in the coming weeks, considering the impact of Covid-19 and the chaos of this summer’s GCSE exams.

Skills minister Gillian Keegan said the early indications were that recruitment had progressed “well in the circumstances” and produced a “viable cohort” across the country.

The first ever T Levels – which have been five years in the making and described as the “gold standard” in technical education to sit alongside their academic equivalent A-levels – launched this month in three subjects: construction, digital and education and childcare.

In what is believed to be the first analysis of T Level recruitment, FE Week asked each of the 44 colleges and schools set to teach the new qualifications how many learners they had managed to enrol against the target they set in each subject at the beginning of the year.

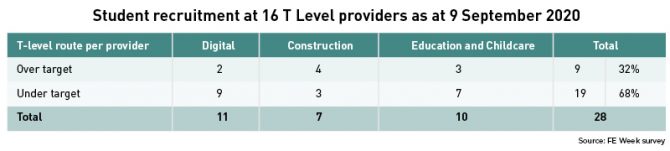

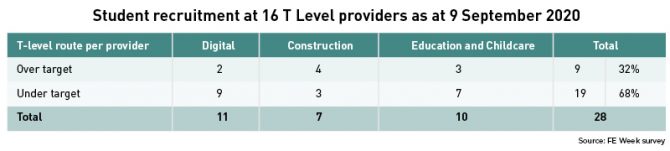

Twelve colleges and four school sixth forms were able to provide breakdowns and, between them, they had set 28 different enrolment targets. Of those, 19 (or 68 per cent) were under target.

Colleges and schools found construction the easiest subject to attract students, followed by education and childcare (see table).

Digital proved to be the biggest challenge. Eleven of the 16 colleges and schools that spoke to FE Week are teaching the digital T Level, and nine of those failed to meet their “modest” targets.

Colleges said that there was an issue with young people’s understanding of the careers available through a digital qualification.

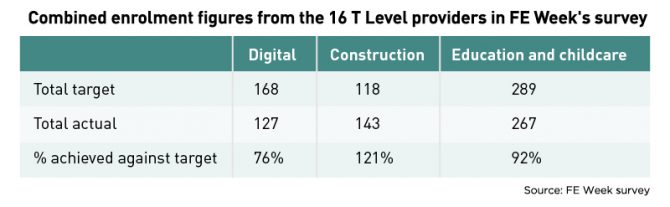

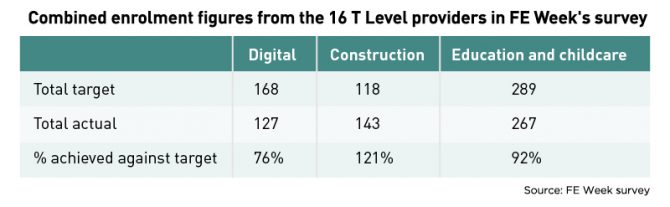

When combining all of the data provided by the 16 schools and colleges, the figures show that 143 students have enrolled on construction courses against a target of 118 (21 per cent above target), 267 students have enrolled on the education and childcare T Level against a target of 289 (8 per cent below target), and 127 have started a digital T Level against a target of 168 (24 per cent below target).

Some colleges were able to buck the trend, however, with Chichester College Group – which is based in Keegan’s constituency – standing out in particular.

The group set a target of 12 students for digital but ended up enrolling 21. It aimed for 24 in construction but has taken on 43 students and, for education and childcare, it sought 18 students but actually enrolled 39.

The recruitment success at the group, which encompasses five colleges in the south of England, has led to it forming additional T Level classes to cater for the larger than expected cohorts.

A Chichester College Group spokesperson said they were “surprised” at just how well the recruitment had gone in each subject, and put its success down to an “integrated but consistent” marketing approach over the past year.

This included a “dedicated digital marketing campaign” that mostly involved paid-for social media adverts, targeted at 16 and 17-year-olds mainly on Facebook, as well as Google adverts.

The group’s “robust” school liaison team had also made pupils in neighbouring schools fully aware of T Levels over the past year, including virtually when the pandemic hit.

Chichester’s spokesperson added that the extra time that students and parents had to research T Levels over the summer, as well as the achievement of centre assessed grades – which were reportedly inflated in many cases – will “all have contributed to our recruitment”.

While FE Week’s survey offers an indication of early T Level recruitment, a full comprehensive view of demand is unlikely to be available for some months to come.

Bridgwater and Taunton College, for example, said it was staggering its enrolment process this year because of Covid-19 and was therefore not yet able to provide any figures for T Levels.

Many other colleges told this publication that their enrolment processes will continue into late September.

David Hughes, chief executive of the Association of Colleges, told MPs on the education select committee this week that the early response from his members was that there is “good demand from young people and they’ve got employers wanting to do work placements”.

He added: “It is a good start – but it is very low numbers.”

Hughes continued: “The really important bit is sticking at it and making it work and adapting it over time. It’s very easy just to kick them and say they are wrong.

“Everyone needs to get behind T Levels because we need really good high-status technical education for young people with a sense of a broad programme which helps young people to develop a broad range of skills for their whole career.”

When the timeline for rolling out the first three T Levels was announced, the Department for Education set a target of recruiting around 2,000 students in the first year.

In order to increase interest, ministers launched a £3 million “NexT Level” campaign in October 2019. This was controversially put on hold in the first few months of lockdown following orders from the Cabinet Office to focus adverts on updates about the coronavirus pandemic.

Answering a parliamentary question from Damian Hinds, a former education secretary, on early T Level recruitment numbers this week, Keegan said: “All indications are that recruitment has progressed well in the circumstances and a viable cohort of young people will benefit from taking these new, high quality qualifications, leaving them in a great position to move into skilled employment or further training.”

The skills minister added that having 44 colleges and schools teaching the first T Levels this September was “testament to the hard work and dedication of staff in these organisations”.

While T Level numbers appear to be getting off the ground slowly, it would appear recruitment of 16 to 18-year-olds across other level 3 courses in colleges more generally are booming, as FE Week found after speaking with seven leaders this week (see page 18 of this week’s FE Week edition).

He added: “It is also clear that, as the impact of lockdown is felt across the wider economy and students digest the summer examinations debacle, more young people are looking for an education which prioritises the skills and aptitudes they will need in their future careers rather than simply ‘teaching to the test’.”

He added: “It is also clear that, as the impact of lockdown is felt across the wider economy and students digest the summer examinations debacle, more young people are looking for an education which prioritises the skills and aptitudes they will need in their future careers rather than simply ‘teaching to the test’.”