Shifting responsibility for skills between two government departments risks further destabilising the “sofa surfing” policy area, experts have warned.

The surprise announcement that skills will move from the Department for Education to the Department for Work and Pensions came last Friday after Angela Rayner’s resignation triggered a Cabinet reshuffle.

Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer appointed trusted problem-solver Pat McFadden as work and pensions secretary under an expanded brief.

McFadden reportedly told DWP staff he will be “expanding” access to skills training to tackle stubbornly high numbers of young people who are not in education, employment, or training (NEET).

However, it remains unclear which skills budgets this new growth-boosting “super ministry” will hold alongside employment and welfare.

Neither the DWP, DfE, nor Downing Street would comment on how skills programmes and budgets will be carved up between departments.

However, FE Week understands the adult skills fund (ASF), skills bootcamps, and other DfE policy levers for getting adults into work are likely to move to the new department, while decisions are yet to be made on who has responsibility for apprenticeships and Skills England.

The government has confirmed that Jacqui Smith will continue as skills minister but her role will straddle both the DWP and DfE, where she will retain responsibility for higher education and elements of FE that will stay at the DfE, such as 16-19 funding and college oversight.

Realignment or upheaval?

Experts and sector leaders see the move as an opportunity to tackle unemployment rates with a long-needed alignment of skills training with employment support, reinventing the role of Jobcentres, and reducing “frustrating duplication” between some DWP and DfE training programmes.

Sector leaders have been speculating about how the government plans to rapidly align work and welfare policies with skills in a way that will impact growth, productivity and employment rates.

Former skills minister Robert Halfon said the move will have “pluses”, such as creating a “coherent, focused approach” to tackling unemployment and removing “frustrating duplication” caused by two departments running parallel training schemes.

But he warned that “another upheaval” in government, soon after the launch of Skills England, risks “confusing the policy landscape” for learners and employers.

Moving the brief risks the government being distracted by “moving the furniture around” rather than important issues such as achievement rates and recruitment of FE staff, he added.

Tim Leunig, ex-government adviser and director at Public First, said: “My own view is that ‘machinery of government’ changes are a nightmare, and usually lead people to think about internal issues, not the real issues in the country.

“Things like incompatible data storage systems, analysts and policy people who need to be divided into two, teams who are based in a DfE location that has no DWP office and have to commute a long way, or seek a new job, sometimes with a real loss of expertise.”

Joined up policy dreams

Working-age benefits are projected to rise from £48 billion to more than £70 billion by 2030 and more than 900,000 young people not in work or training.

Having direct control over skills funding could bolster DWP’s efforts to target youth NEET numbers, which have so far been limited to funding pilot-style regional programmes known as ‘youth guarantee trailblazers’ with a relatively small overall budget of about £45 million per year.

Stephen Evans, CEO at the Learning and Work Institute, said that moving skills is an opportunity to “genuinely join things up” by offering training to the estimated 4.5 million out-of-work people who have low numeracy and literacy skills.

Figures within the sector note that skills has been part of six different government departments in the past 30 years.

“[Skills] has been around the houses, it’s the sofa surfing policy area… but what matters really is what you do,” Evans added.

“I would say the risk is that just we carry on as we are in a different building – the opportunity is to genuinely join things up a bit.”

This could include rationalising the various training programmes aiming to help people gain skills for work and merging the array of plans to improve skills, employment, and growth that local areas are now required to produce.

Association of Colleges chief executive David Hughes added: “The big risk with this shift is that senior officials spend lot of their time negotiating the change and implementing rather than getting on with the day job.

“The opportunity is that we’ve got another secretary of state fighting for and advocating for funding for post-16, skills, apprenticeships and the adult skills fund.

“So I think the positives outweigh the negatives for me. Isn’t it great that someone wants it and really thinks they can do something?”

‘Avoiding the trap of short-termism’

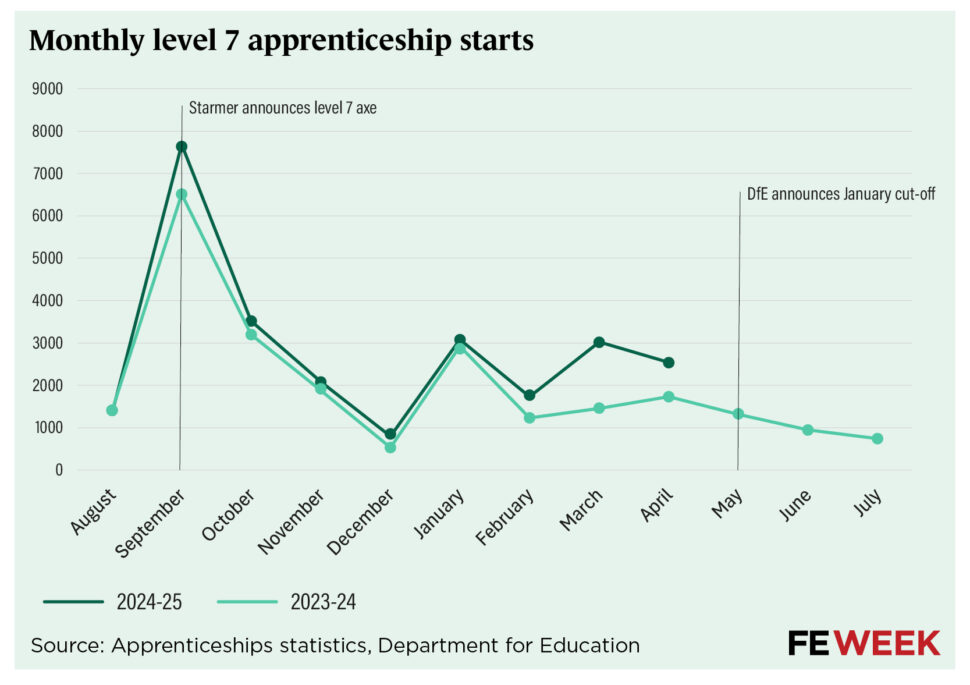

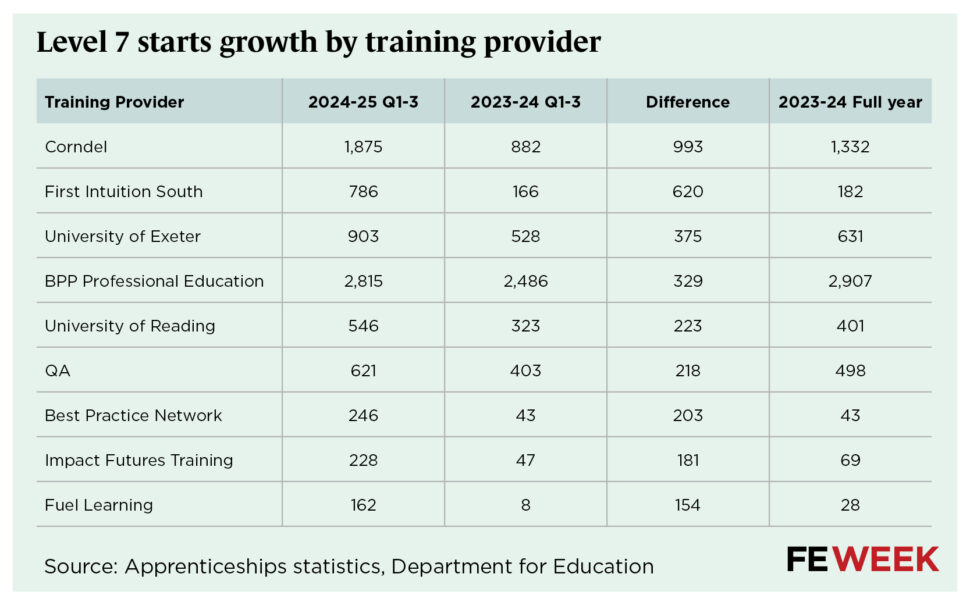

The skills policy control shift comes at a busy time for FE, as Labour continues to turn the apprenticeship levy into a growth and skills levy offer, and ahead of a post-16 white paper expected before Christmas.

Without apprenticeships, the work and pensions secretary will gain limited extra funding from taking over skills, as about two thirds of both adult skills fund and skills bootcamps are dished out to mayors and local authorities to manage.

Ben Rowland, CEO at the Association of Employment and Learning Providers, said apprenticeships are critical for Jobcentres to be able to get people “onto a more productive path”.

He added: “If they’re keeping apprenticeships in the DfE, it doesn’t give Pat McFadden tools he needs – he needs to have apprenticeships, short courses and [higher technical qualifications] at his disposal.

“Otherwise, it’s a non-significant announcement.”

For Halfon, who first became skills minister when the policy brief moved from the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS) in 2016, the reorganisation has potential to deliver a “long-needed” joined up approach to skills and employment.

He added: “But success will depend on avoiding the trap of short-termism and ensuring that quality apprenticeships and skills programmes remain at the heart of our national mission.

“The stakes are high: get this right, and we can transform lives and boost productivity. Get it wrong, and we risk undermining years of progress in skills development.”