The biggest losers in the government’s mission to boost apprenticeships are traditional crafts for whom the term “apprenticeship” was initially intended. We investigate how longstanding training going back to the Middle Ages is now under threat.

Crafts passed on since England’s original national apprenticeship scheme was introduced in 1563 are now considered too small in scale and specialist to conform to our standardised apprenticeships system. Only a quarter of the UK’s 259 heritage crafts have approved apprenticeship standards – and far fewer are being delivered.

But all is not lost. The popularity of TV shows such as BBC One’s The Repair Shop, “how to” crafting videos and heritage-themed films and festivals are breathing a new lease of life into some traditional skills.

Apprenticeships non-starters

Organ-building and watchmaking – skills passed down since the 1500s and now deemed “critically endangered” – have been available as apprenticeship standards for five years but have yet to enrol any recruits.

Stained glass-making, traced back to the 7th century, has recently been declared “endangered” by the charity Heritage Craft, which publishes an annual “red list”.

Its apprenticeship failed to attract any interest, a year after jumping the many hoops involved in getting approval from the Institute for Apprenticeships and Technical Education’s (IfATE).

Heritage Craft partly blames its demise on that of another craft, mouth-blown flat glass-making, deemed “extinct” after the only company making it, English Antique Glass, was forced to leave its Birmingham home because of redevelopment. This had a “knock-on effect” on stained glass restoration.

Other apprenticeships designed to keep traditional skills alive but which have failed to attract any apprentices include clockmaker, assistant puppetmaker, bookbinder and blacksmith, all because of a lack of ability to procure a training provider, an end-point assessor or, in the case of bookbinder, both.

The process of trying to get an apprenticeship off the ground has been particularly challenging for The Institute of British Organ Building (IBO).

It first got an apprenticeship standard over the line in 2017 (after eight years of trying), but it then took until 2021 to find a training provider, the Building Crafts College. In the meantime IfATE said the standard required a review – despite never being taught.

Its accrediting body NOCN does not employ organ-building assessors, so three people within IBO’s ranks were tasked with assessing its scheme under the NOCN umbrella. IBO’s Carol Leevey describes this as “quite ludicrous”.

Last year the standard was approved with maximum funding (£27,000), but the Building Crafts College can no longer commit to running the three-year course.

The college’s building manager, Joe Mercer, says it had concerns over organ-building being “viable over a long period of time”. “There is pent-up demand, but it is a very disparate industry. We want to know there would be subsequent cohorts.”

Meanwhile, organ-builders are continuing to retire. “The worry is firms close without a successor, because they couldn’t properly train anyone,” says Leevey.

Heritage Craft’s executive director, Daniel Carpenter, blames the lack of apprenticeship starts on training providers requiring “bums on seats”. “It’s just not economically viable for them to have such small cohorts. Increasingly, they’re pulling out from this provision.”

Leevey urges the government to recognise their apprenticeships model “doesn’t suit crafts with five new people a year”, and to “compensate providers to offset losses they incur in teaching smaller groups…to demonstrate the national heritage value these crafts have”.

IfATE’s chief executive, Jennifer Coupland, acknowledges the “particular challenges” heritage industries face.

“How small a number of apprentices do you need to make a cohort viable? That doesn’t mean those skills aren’t needed. It’s a balancing act.”

This year, IfATE is instead prioritising reviewing apprenticeships with “large numbers of apprentices, new and emerging technology or new regulatory requirements”.

Meanwhile, the government seems unaware of the problem. Skills minister Robert Halfon says he is “not quite clear why [heritage crafts] wouldn’t be suitable to apprenticeship standards”.

“If there are problems, of course I would look at it because I want to support these traditional paths wherever I possibly can.”

Alternative solutions

Any government help may come too late as some heritage businesses have turned their backs on the apprenticeships system and found other means to train learners.

Adam Davison, from Durham, 22, sees himself as being on a three-year “apprenticeship” (but not an official one), with his employer, the organ builder Harrison & Harrison, dictating what he needs to learn.

After studying chemistry, maths and physics A Levels with the intention of going to university, he decided to be more “hands-on”. “I love being able to see the finished product.

“Having to explain to people what I do is the hardest thing – most people are surprised to hear the [organ-building] industry exists.”

Saddlery guilds have existed in England since the 12th century, but for Patrick Burns, the founder of the Walsall Leather Skills Centre, it was not financially viable to “jump through all the hoops” involved in offering saddlery apprenticeships.

Instead, his saddlers can undertake traditional-style, informal apprenticeships through saddlery companies. The cost of paying for courses “doesn’t put people off” – he gets about five enquiries a week. “My problem is finding tutors at a reasonable price that keeps courses affordable.”

Crafting themselves

Carpenter believes heritage crafts are “riding the wave” of a revived public interest, prompted by people “re-evaluating their lives after Covid” and “wanting to do something productive, where they can see the outputs of their labour”.

Creators sometimes teach themselves the traditional skills, with online help. Gordon Coe, a Suffolk college-trained fabricator and welder, specialises in handmade armour and pendants inspired by his love of Star Wars as well as history.

While a medieval blacksmith forging iron spent seven years “indentured” to a master craftsman, Coe works independently through his company Mendo Metalsmith. He forges steel and perfects his craftby “playing and experimenting” and watching blacksmiths’ TikTok videos.

These only provide “snippets of information”. “They never give you the full ‘how to’ – there’s always an element missing. That’s the fun of it, because you then go practise.”

Carpenter highlights how 98 per cent of heritage crafts are micro businesses of 10 or fewer employees, making it harder for craftsmen to “afford to step away from production to train somebody”.

That’s the case for Coe, who would not consider taking on an apprentice. “Trying to teach someone would be difficult when I need to be getting on with work to meet my deadlines.”

Carpenter believes some older makers do not pass their skills on because they believe young people are not interested in heritage crafts. “There’s a breakdown of communication between generations, they don’t know how to talk to each other about it.”

Reimagining old crafts

Both Coe and Nicola Hibbard, a historian who specialises in painting using plant-dye paint on papyrus paper, showcase their talents at historic fairs and festivals, which are gaining popularity, partly inspired by TV shows and films such Game of Thrones, Lord of the Rings and The Last Kingdom.

Hibbard, who paints in the same way as people did in Egyptian, Roman and medieval times, says her skill is “as much about chemistry as art” because of the time it takes to source her paints.

But although her historical research gives her some ideas, she’s learnt more through experimentation because of “deliberate inaccuracies” in the historic documents of the time.

“The trouble with teaching yourself these skills is that in the 14th century, the guilds wanted to maintain their market monopoly. Half the paint recipes are fakes…because they were concerned talented amateurs were cutting in on their business.”

The future

Heritage crafts in England employed 210,000 people and contributed £4.4 billion a year to the economy, according to research commissioned by the government in 2012. But Carpenter laments the lack of “political will” to explore whether that is still the case.

The UK is one of only 12 countries in the world not to have ratified the UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. “The rest of the world understands the importance of those skills, but sadly we don’t.”

But Carpenter is hopeful there is a solution that could solve some of the challenges holding craft apprenticeships back. An organisation with private sector backing is currently seeking to set up a residential heritage crafts training centre in the south of England to provide the classroom element of apprenticeship training.

There are challenges on the horizon too as technology is making items easy for anyone to mass produce. Coe is concerned about the future of metalcraft because 3D printers can now print wood and metal filaments. “One person can create a template file [online] and anyone can now go click and 3D print it.”

Carpenter believes heritage crafts can thrive alongside the digital world, pointing to heritage crafters who have gained sizeable online followings.

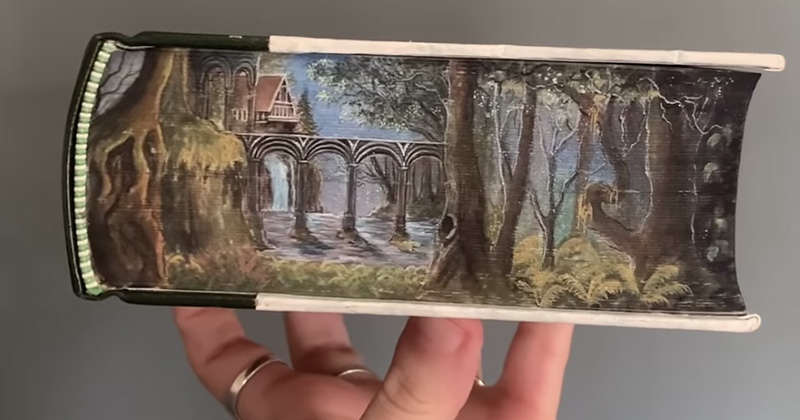

They include Denzel Currie, a former graphic designer whose rug tufting videos went viral over lockdown and who has since worked with big brands Jaguar and Nike, and Maise Matilda Jackson, an art historian who practises fore-edge painting on books, a technique from the 13th century.

A video of her painting the edges of a copy of The Lord of the Rings has been viewed more than 7.4 million times.

Carpenter warns those practising endangered crafts sometimes feel “pressure” upon “realising that the buck stops with them”. “If they don’t make it a go of it, the craft will die out. We’re hoping that doesn’t weigh too heavily on them.”

Jackson is well aware that her craft, now critically endangered, is “really unique to English artistic culture. It’s really important for me to keep it alive,” she says.

If you genetically modified a pear to taste like an apple, but still look like a pear – what would you call it? And could you still compare the fruit to standard apples and pears…

You could apply the same notion to apprenticeships. Originally an apprentice would serve under someone who was considered a ‘master’ of that trade or skill.

In modern apprenticeships, many apprentices are managed or overseen by someone with little direct knowledge, skill or experience of that role, yet we insist on calling them apprenticeships and treat everything with the same label as being comparable.

Apprenticeships that mirror the original apprenticeship model in how they operate still exist, others taste of apple!

One size very rarely fits all.