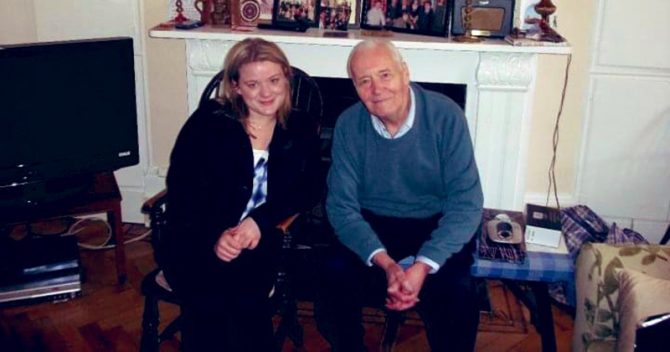

Jo Grady, general secretary of the UCU, swept to the leadership at a young age pledging to improve wages in FE. Here she explains why members shouldn’t wait for others to make it happen

“What would Dolly Parton do, essentially? That’s what I ask.”

The blonde country singer does not at first seem the most obvious role model for Jo Grady, general secretary of the University and College Union, formerly a lecturer in employment relations at Sheffield and Leicester universities. Grady is young for a trade union leader, having won the leadership at just 36 years old, and, like her heroine, is blonde and grins widely. But it’s taking action that won Parton to Grady’s heart.

“I know it’s going to sound like an absurd thing to say, but Dolly Parton didn’t just sit around saying, ‘Isn’t it awful children can’t read?’ She set up the Imagination Library,” says Grady, referring to the singer’s huge literacy initiative.

Rolling your sleeves up and getting stuck in was the platform on which Grady won the leadership in 2019, securing 64 per cent of the vote (almost double the runner-up’s) on a turnout of 20 per cent. It was a platform of fighting talk, sweeping in after her predecessor, also a woman, had spent 12 years at the helm.

Despite never having run an organisation before, Grady entered confidently and in particular said it was FE where the union had “made the least progress in protecting or improving our members’ wages” and that it should spend more of its “fighting fund” to support striking workers.

In the past two years, Grady appears to have put her money where her mouth is. Right now, UCU members across 11 colleges are casting ballots on whether to go on strike over pay (the pay gap with schoolteachers currently stands at £9,000) and redundancy plans. The ballots close in mid-July and strikes would take place in the autumn.

Meanwhile, 600 prison staff across almost 50 prisons and young offender institutes have walked out four times since May, with two strikes just last month. The union leader has also been found on picket lines everywhere from Nottingham College to Islington College. As at January, the union had about 38,000 FE members.

But her drive for action doesn’t mean Grady sees herself as a charismatic trade union-Dolly Parton type, leading the charge for a fairer 9 to 5. When she arrived, she says, many members had forgotten it was they – not the UCU leadership – who should be taking action.

“I get really annoyed when people say, ‘Someone should do x’ or ‘The union should do y’. And I say, ‘Why don’t you do it, you’re in the union? Stop using third-party language. Find other people, find your community.’”

A more passive attitude towards union membership arose during the New Labour years, says Grady, and was the subject of her PhD at Lancaster University (she got masters funding and then stayed on). “It was on the extent to which trade unions had collaborated with a neoliberal agenda, with New Labour,” she explains.

“I think there was an internalisation following the 1980s, with the huge attacks on the trade union movement, that winning was difficult. I think there had been a loss of courage.” As a result, trade unions moved to a “service model”, rather than a collective action model, she says.

“It was an assumption that people were joining not because they were committed to progressive politics and social justice, but they just wanted stuff. They wanted representing, almost like an insurance card.”

At the same time, she says, unions had begun to accept a watered-down vision for members. She joined UCU aged 25 as a lecturer, and by age 35 had been left unimpressed. “It seemed to be about just managing the decline of terms and conditions,” she frowns. “It doesn’t mean they weren’t fighting, but there was a sense of just defending what we’d got or making the decline palatable.”

“What that does,” she continues, “is create quite a passive membership, that fosters a sense of dependency that someone else should be doing things for them. For me, it should be the opposite. That is not the union I want. It’s changing to be more member-led.” It’s a heady mix of collective action via personal responsibility.

Grady credits her Catholic grandfather with encouraging her towards university, and, once there, regularly checking when she’d be a professor. But her meteoric career was not expected by her family: “It was seen as a bit of an unusual thing, but it was also like, ‘Oh, that’s Joanne’,” she laughs.

I comment she’s a self-made woman, but am carefully corrected. “I don’t really like that idea of a self-made person, someone who’s escaped their working-class roots,” says Grady lightly, and you can see the teacher coming through.

“It completely erases the communities that working-class people are brought up in. The success for me is fundamentally embedded in the community I came out of.” She laughs again. “I genuinely credit a lot of my skillset to working in a pub.”

Her father was a miner in west Yorkshire earning a good wage, and Grady was brought up in Wakefield on a council estate she remembers as a “triumph of social housing – beautiful, with wide roads, trees, terraces, everyone had a garden”. But pit closures meant the household, with three children under four, went without a salary for a whole year. Afterwards, her parents opened a pub and some of Grady’s earliest memories are heading through the pub tap room to the flat upstairs.

Grady doesn’t attempt to ham up a childhood of hardship, as politicians occasionally will. “We could afford books, and when I wanted to go to university, we had money to help me go. I sailed through with a lot of material comforts, but for the gift of birth, it could have been different.”

Grady recalls those differences. On non-uniform day, some children couldn’t afford the pound for charity. One particular incident stands out. “There was a girl who I think was one of seven, the rest were boys. The household got nits and they all had their heads shaved, including the girl. I remember as a child being horrified that things that didn’t cost a lot of money, like shampoo, were being denied to people.”

The environment fostered a strong sense of unfairness, and also grounded Grady. “You’d meet such an array of people in the pub,” she recalls, chuckling about a millionaire regular. “It was the social living-room of the community. It’s a really grounding experience – that no one is better than you, but you’re not better than anyone else.”

Steeped in community, Grady has been intent on building community among UCU members. Last year under the union set up a “strike school”, she says, which 800 members have been through already. It’s a deliberate inversion of the service model Grady sees as so disabling.

“It’s about, if you want to win, campaign, ballot, these are the things you need to do.” The first school was in September last year, with two classes a week over six weeks, and the second school finished this week.

It’s also a pushback against the Trade Union Act 2016. Fiercely opposed by unions, it requires industrial ballots to attract a 50 per cent turnout in order for any vote to be legally valid. But the real catch, says Grady, is that ballots cannot be electronic.

“The struggle is the paper ballot. You have to let people know it’s coming, post it to them, they have to post it back,” she says. “I would argue the government did it to make it as difficult as possible to take part in action.”

Another key barrier to creating effective pressure is the lack of coverage of FE in mainstream media. Grady thinks the prison strikes – held over Covid concerns for staff, as well as the “barbaric” lack of education resources for prisoners, she says – were well covered “because they get what prisons are, even though they’re part of FE”. But there was a “silent avalanche” of Covid in colleges that failed to get proper attention.

“I don’t know why the media is intent on erasing FE from copy. I’ve been constantly pointing out colleges must be treated differently to schools. They are adult spaces, there’s a huge range of people – stop talking about them like they’re for children.”

For September, Grady says “if the government fails to offer young people vaccines before the start of term then appropriate steps need to be taken to protect students and staff”, with colleges needing to “have plans in place for remote learning in case of further Covid outbreaks”.*

I ask why UCU has argued for remote teaching when schoolteachers were giving face-to-face lessons.

I don’t know why the media is intent on erasing FE from copy

“The argument for schools was more about the mental wellbeing and educational development of children, and the fact parents would have to stay at home,” she replies. “The complexities and concerns were not transferrable to the HE and FE sector.” Given the mental health crisis engulfing FE and university students, it seems odd to assume these issues were not massive for these students too. Many college staff I speak to say their students can’t take any more time online.

But Grady is fighting for her members – or rather, helping them fight for themselves. She says she ran as general secretary in large part because as a lecturer she was burning out, and was either going to “change the sector or walk away”. And she’s not finished yet.

“There would be nothing stopping me running again if I felt the job wasn’t done, and there would be nothing stopping me going back to teaching. Time will tell.”

As Dolly says, she’s holding out for When Life is Good Again.

*This article was updated on 6 July 2021 to make clear Grady is calling for young people to be vaccinated before the start of term

Your thoughts