College catchment areas can owe as much to constituency borders as they can to the routes of local buses clad with enrolment day advertising.

But it was far simpler for Professor Ed Sallis when he was principal of Highlands College — his catchment area limits were the Jersey seashore.

“There wasn’t the level of competition because we were the only college, and we had potentially a finite number of learners,” he says.

“We had to think of ways of being relevant for the whole community.”

Sallis put on honours degrees with Plymouth University because “what people wanted was not just to foundation degrees but to do honours degrees because even if they couldn’t get off the island they wanted the whole thing”.

He adds: “We developed one or two of our own quals that were specific to the finance industry in Jersey, particularly around the issue of trust companies which don’t really exist anywhere else in the UK. So it was a lot of that type of thing.”

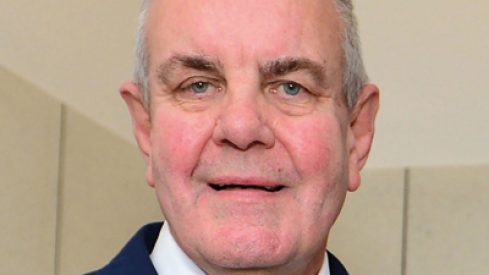

Sallis, aged 66, came to the attention of England’s FE and skills sector in December when it was announced that he was to head the Education and Training Foundation ETF taskforce looking at the teaching and accreditation of maths and English —including Functional Skills but not GCSEs— for learners unable to reach D grade GCSE.

“At the moment we don’t have an answer to what employers really think of Functional Skills because it hasn’t been researched,” he says.

But what is clear, he says, is the importance of basic English and maths skills, in whatever form they’re taught.

“There are an awful lot of people in FE who do have a life-changing experience, but they can’t have it unless they’ve got the basics,” he says.

“To some extent getting a qualification, in level one Functional Skills or whatever, is a real achievement in a way that going from an E to a D at GCSE isn’t.

“Having said all that, I do very much agree with Professor Alison Wolf that GCSE is a gold standard, so you should give as many people as possible the opportunities to do it — but on the other hand, you need some stepping stones.

The difference in Jersey was that we weren’t funding for specific groups of learners — we just got a lump of money really

“What we need to do is to make certain that the stepping stones are as good as they possibly can be.”

Sallis’s own career stepping stones started at 16 having left school to train in chartered accountancy. But it lasted less than a month before he went back to school to differing reactions from mum Winifred and dad Leslie.

“My mother was a very interesting person who was a secretary in Churchill’s war room during the war,” he explains.

“She was passionately interested in education. She was one of these people who didn’t have the chance herself really, but later on in life she did a lot of Workers’ Education Alliance classes and began organising them.”

His father, a salesman from East London who became vice-president of an American multinational in London, was less sure.

“My father was a typical East End chap who made good. He was remarkable,” says Sallis.

“He thought I ought to do something much more business-orientated — qualifications that didn’t necessarily go somewhere wasn’t a world he understood.”

After sixth form and a degree in politics and economics at the University of London, Sallis found himself back in accountancy, and realising he didn’t really want a future as a tax inspector, he again took inspiration from a friend who worked at Peterborough College.

“He seemed to be having a far more interesting time of things than I was, so when I saw an advert in the paper for a lecturer in general studies, and I hadn’t a clue what it was about, I applied. I was interviewed, and I got a job in FE,” he says.

The job was at Acton Technical College (now part of Ealing, Hammersmith and West London College) where general studies was a newly-introduced subject at a college that hitherto only taught science and engineering.

“Today, you wouldn’t have a college that just did engineering and science — it’s interesting to see how FE has developed and matured over the years. And it was terribly small, but one of the good things about it was they did a lot of broadening studies, which included literacy and numeracy work and economics, with apprentices,” he says.

“And the great thing in terms of my career was that I did get to teach a whole range of people a feel of what was out there.”

The college had another long term benefit for Sallis’s career.

“The principal at the time was a chap who gave me quite a lot of time and encouraged me to think about FE as a career,” he says.

“And although I thoroughly enjoyed working there, he said: ‘There comes a point where I’m not going to promote you, you’ve got to go somewhere else as it’s going to be better for your career’.”

And Sallis, a former director of the Centre for Excellence in Leadership who was awarded an OBE for services for education in 2010, says he “took that on board”, moving to Hackney in East London, to Slough, to Somerset, to Guildford and to Bristol before making the move to Jersey, where his experience was one that would likely turn principals in England green with envy.

“The difference in Jersey was that we weren’t funding for specific groups of learners — we just got a lump of money really,” he says.

He adds: “But we had to make sure that we offered qualifications sometimes where there were very, very few learners and the programmes weren’t particularly economic to run.

“There wasn’t a college down the road so you had to make certain that if there were three or four learners for something that employers wanted you could still offer a programme. You couldn’t say ‘sorry, it’s not viable’ — you had to do it.”

It was the uniqueness of the situation in Jersey that attracted Sallis to the role, although he says he’d always been “ambitious”.

“We don’t have an answer to what employers really think of Functional Skills because it hasn’t been researched”

“I’d always thought I could be a principal,” he says. “It was just waiting for the opportunity.”

Throughout though, he says he’s always been keen on “keeping a foothold in the classroom”.

“Because actually I think it’s important,” says Sallis.

“It’s difficult, and it becomes, I suppose, in the end, an almost impossible thing to do, but I’ve always tried to be as close to the classroom and to be in it as much as I can.”

In all that moving around, in the early 90s Sallis also found time to do a PhD in quality management in education, something which at the time “was a strange new concept”.

But even today, he says, pedagogy in FE is “under-researched”.

“There’s a lot more going on than there used to be, but when you compare it with the amount of research into schools and higher education, really there is an awful lot of stuff we don’t know.”

Sallis’s ETF review is due to conclude next month.

It’s a personal thing

What is your favourite book, and why?

At the moment I’m reading Juliet Barker’s England, Arise. It’s a history of the peasants’ revolt of 1381. Medieval history is one of my passions

What do you do to switch off from work?

I walk on the beach — I’m fortunate enough to live in Jersey and the beach is just down the road. And I play a very bad game of golf. Basically, I like being out in the fresh air

What’s your pet hate?

People who are not genuine. Hypocrisy

If you could invite anyone to a dinner party, living or dead, who would it be?

I’d probably ask Sebastian Coe, because I’m very interested in athletics and sports, and I admire the work he did with the Olympics. I’d probably ask Winston Churchill as well. That would make a nice dinner party

What did you want to be when you grew up?

I didn’t have a clue

Your thoughts