Work placements are the most critical element of a T Level qualification, but employers are put off from offering them by health and safety concerns, time pressures, bureaucratic hurdles and cost fears.

While the mandatory 45-day or 315-hour industry placement is regarded as the main reason why students should sign up for T Levels, colleges are now struggling to persuade enough employers to provide them.

Just over 1,000 students from the first wave of T Levels got their results in August last year. Of those, only 6 per cent did not complete the work placement, although there was some flexibility in place to reflect the impact of Covid 19 on businesses.

So, with eight more T Levels being rolled out by 2025 and learner volumes set to rise significantly, it is unclear whether enough placements will be available to meet the increased demand.

A T Level professional development programme report published last week cited “too few employer placements and insufficient employer engagement” as one of five factors affecting current T Level delivery.

Dr Nuala Burgess, who undertook research on T Level provision for King’s College London, found some colleges “struggling to get work placements” for students. She puts this partly down to the “economy of the place”.

“It’s not the fault of the colleges, the young people or even the employers, there just isn’t the work to give them,” she says.

Dr Burgess believes the first colleges to roll out T Levels had an “ethos and reputation” which meant they would not pass anyone who had not undertaken placements. But she questions whether that will be the case as the roll-out accelerates.

She criticises the “ad hoc and messy” nature of the process involved in setting up work placements which differs for each college, with arrangements sometimes dependent on “a lecturer with a mate”.

“I definitely got the feeling that it was really difficult to find these work placements. You never have that nice joined-up system… something is missing.”

Lack of awareness

One problem is that T Levels are still relatively unknown. Research from earlier in 2022 found that three-quarters of employers had not heard of them.

Steve Joyce, director of human resources for Airedale International Air Conditioning, a manufacturer based in Leeds, was not aware of T Levels despite the company’s local college, Leeds City College, offering T Levels in engineering and manufacturing. But Joyce says the “biggest barrier” to offering placements is their “duration”.

The apprenticeships and year-long placements that Airedale offers degree students work “really well” because students are given “a meaningful piece of work to do”, whereas shorter placements are “more difficult”, he says.

Helen Clements, social value manager at Morgan Sindall Construction, says placement duration is also a problem for the construction industry. T Level placements can only be split across up to two employers and, “unless it’s a large housing estate, none of the building projects last for long enough”.

Furthermore, most site workers are self-employed and paid a day rate, so they “don’t want to give up their time to mentor a young person, even though it is short-sighted of the industry”.

Clements says the challenge is even harder for colleges based in rural locations without public transport links to construction sites.

Rigid course requirements

Although the construction industry is booming in Southend, employers offering placements for South Essex College’s on-site construction T Level, which includes a specialism in carpentry and joinery, have generally been “one-man bands”, according to course leader Simon Parker.

The five main contractors Parker has approached have been unable to offer “carpentry-specific placements”, instead offering work “predominantly shadowing the site manager, the design team or the corporate social responsibility side of things”.

“Those are all things we teach, but we can’t offer that as a placement. I’m trying to tap into their supply chain, which has its own difficulties because they’ve got a job to get finished. Providing placements is not their focus.”

Tom Smith, who runs Surelec Electrical in Ipswich, had never heard of T Levels but is deterred from offering placements by the “extra time” involved in training someone up. “You might be putting all that effort into them and you’re not going to see anything at the end of it,” he says.

Smith is also put off by fears that his insurance premiums will soar. “For an apprenticeship, the insurance is all fine. But [for work placements] they want a lot more money because it involves someone without any experience, so the risk is higher.”

Parker is urging the government to allow more flexibility by enabling placements to involve other types of experience, rather than “just that specific trade” – in his case carpentry – to encourage more employers to sign up.

“Then, once the student is in place in that system, they could swing towards the carpentry with that supply chain [on site], because you’ve got that link in.”

Although there is still a “lack of clarity about what T Levels are”, Parker believes this is starting to shift three years into the roll-out. The DfE’s portal for businesses to register interest in providing placements has generated “a couple of leads” for him, one of which is leading towards a placement.

Paying for documentation

Another major hurdle is that T Level students are required by the industry – although not by law – to carry a Construction Skills Certification Scheme (CSCS) card when they are on a building site for more than 19 days. But colleges are not funded to provide the card, which costs around £110 per student.

Jessica Berry, vice principal for curriculum quality and innovation at the Windsor Forest Colleges Group, says CSCS card provision is “sporadic” among colleges “because it’s not part of the T Level framework” and “some don’t have the capacity to fund it”.

Similarly, health T Levels do not incorporate the Care Certificate – an agreed set of professional standards which anyone working in that sector has to study. Berry says this “should be built in because it is industry recognised”.

Safety training barrier

For construction and engineering companies in safety-critical systems, there are strict safety rules in place which limit their ability to provide placements.

For example, students are required to undergo rigorous safety training before any placements in nuclear power plants, with under-18s banned altogether from many sites.

Franziska von Blumenthal, head of policy and research at the Engineering Construction Industry Training Board, told a session of the all-party parliamentary group for T Levels that colleges should be building more “simulated environments” for this training to take place as part of T Level courses.

Blumenthal says industries such as mining and motorsports face “similar issues”. “There doesn’t seem to be much movement on the potential that simulated environments have to really open up T Levels to an industry that has a huge skill shortage, is trying desperately to attract young people and is facing these hold-ups,” she says.

But Berry points out that colleges have received funding through the DfE’s industry placements capacity and delivery fund which could be used to create such facilities. They “should be working with” employers to resolve these issues.

That funding has been gradually reducing as T Levels are rolled out and will be gone altogether after 2023/24.

In its place, the DfE recently announced a new £12 million placement fund as a sweetener for employers to cover the costs such as set-up expenses and equipment.

However, just £500,000 from a previous £7 million employer support fund was used during its previous run from 2019-2022.

Science placement challenges

Funding on its own is not the solution. One FE college cited in the T Level professional development report said science T Level placements had been “difficult to deliver”, and the financial incentives for businesses “did not necessarily mean the provider could secure the number of placements needed”.

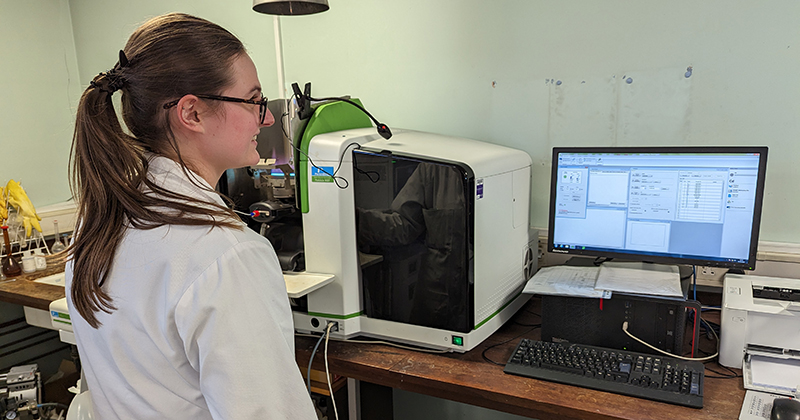

Mid Kent College offers T Levels in construction, childcare, health and science, and Nabil Mugharbel, its director of curriculum, says science is the hardest one to source placements for. The college is “making a lot of effort to make it work”, including inviting science employers to a webinar this week.

Mugharbel explains how it has been more challenging getting placements for students aged under 18 in toxicology, because “where there’s confidential information or potential harm to students, companies don’t want to take the risk”.

“I don’t have the big [pharmaceutical] companies, because they are mostly based in London – students will not travel that far,” he explains.

One company that is hosting students for the college is the local council’s in-house science laboratory, Kent Scientific Services. Its head, Mark Rolfe, says there had been “very little bureaucracy” involved in the process of setting up the placements, but his team “had to work” to make the placements “worthwhile”.

“I suspect what might hold companies back is fear of the unknown. But, once they get into it, they may realise it is actually quite easy.

“The staff in the lab really get something out of this, they really enjoy having young people enthusiastic about what they are doing.”

‘Disgusting and dangerous’ work

Dr Burgess describes work placement quality as “extraordinarily variable”. She recalls one student whose placement involved being sent by a “reputable chain of hotels” to unblock toilets without PPE, which she describes as “disgusting and dangerous” work.

But another construction student got “proper hands-on experience” with a building firm, including using a theodolite and visiting “underwater tunnels”.

She believes that, where placements have worked out, they have been invaluable. “The absolute beauty of this T Level is, when it works well, students come back in the classroom so excited because they have seen it, touched it, felt it. They are incredibly motivated by the experience.”

For Skye, an 18-year-old student at Bury College, it was the hands-on experience which made her opt for a T Level in health: supporting the adult nursing team.

The NHS offered 20 of Bury’s 28 second-year students placements at local hospitals, to shadow staff on the wards, although they are not permitted to undertake clinical work.

Andrea Plimmer, Bury’s assistant director of health and social care, says “it would just be nice in the future if we weren’t just limited to 20 places for our students within the NHS … It’s such a good experience that we’d like to open up as our numbers grow.”

When Skye started her course, she had no idea what area of health she wanted to go into, but it was her industry placement which made her decide to opt for oncology as a career.

“I got to see how cancer can affect not just the person but the family, and how palliative care comes into that,” she says. “It means, when I get into the real world, I’ll understand what I need to do.”

T-levels are indeed not well understood. The opening line of this piece says that work placements are the most critical element of a T-level qualification. As I understand it, the work placement is not a part of the qualification at all; it is a part of the program. Massively over-engineered, poorly thought through, and largely inappropriate for their target learner group, T-levels have been so heavily financed by the public that they are now in the “doomed to succeed” category of DfE cul-de-sacs.

T (Tory) levels are poorly thought out and a product of a false belief that employers will embrace them and provide the work placements. BTEC’s are tried and tested, and delivered by post 16 colleges. Why fix what’s not broken.

Those responsible have been warned time and again about the lack of realism re. T levels

They are badly designed. Some predictions

1. Numbers in FE will dwindle as there won’t be pathways

2. Achievement rates for t levels will make apprentice rates look amazing at 50 to 60 per cent.

Students will leave before

completing work experience.

3. A lot of t levels will recruit no students

4. The qualification landscape will be a complete mess.

5. The civil servants with their new grand titles of directors of this that and the other will blame colleges.

6. The same civil servants will receive their undeserved honours

7. The real reason will become apparent cut college numbers and create a pool of cheap labour and prevent those without the ‘right’ background ever aspiring to HE.