Ofqual is “closely monitoring” an investigation being carried out by Training Qualifications UK into allegations of ‘copy and paste’ assessments, FE Week can reveal.

Earlier this week the exams regulator said it was “looking into” concerns identified by Ofsted during a recent inspection of Northern Construction Training and Regeneration.

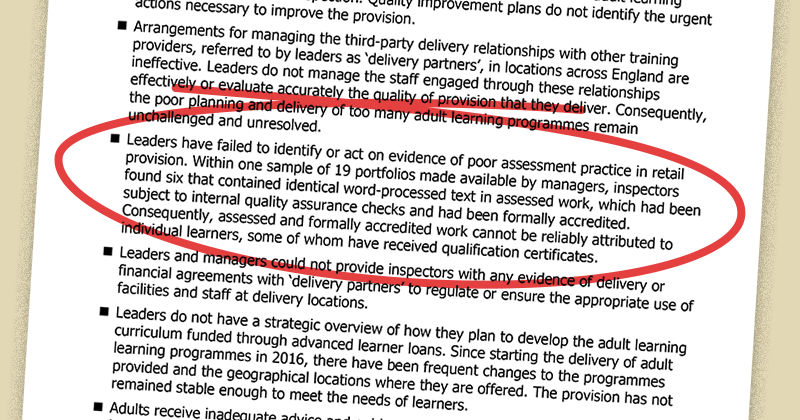

The inspectorate’s report said it had found evidence of assessment practice in its retail provision that was “not consistently appropriate” – including identical word-processed text in six out of 19 sample portfolios it checked.

Ofqual has now confirmed that TQUK had alerted it to “an investigation it is carrying out into suspected malpractice” at NCTR.

“We are closely monitoring TQUK’s investigation,” a spokesperson said.

Andrew Walker, managing director at TQUK, told FE Week that NCTR was approved to offer its retail qualifications and that it was the awarding body affected.

“The centre is currently subject to an ongoing investigation. I am unable to comment further at this time,” he said.

NCTR’s Ofsted report, which rated it grade four overall, highlighted concerns over “poor assessment practice” in its retail provision.

“Within one sample of 19 portfolios made available by managers, inspectors found that six contained identical word-processed text in assessed work, which had been subject to internal quality assurance checks and had been formally accredited,” the report said.

“Consequently, assessed and formally accredited work cannot be reliably attributed to individual learners, some of whom have received qualification certificates.”

NCTR, which hadn’t previously been inspected, had non-levy apprenticeship contracts worth £1,007,046 in 2017/18, the vast majority of which was for 16- to 18-year-old apprentices.

In addition, it had an advanced learner loan facility worth £2.5 million.

At the time of inspection the provider had 423 adult learners on programme, and 75 apprentices.

Last week’s inspection report rated it ‘inadequate’ overall but grade two for its apprenticeship provision.

According to ESFA rules, this means it is likely to have its contracts pulled but it should keep its place on the register of apprenticeship providers.

However, neither the provider nor ESFA has yet confirmed that this will happen.

A spokesperson for the Department for Education said it was “currently assessing Ofsted’s findings” and would be contacting NCTR “to set out the action we will be taking in due course”.

“We will always take action to protect apprentices if a training provider is not fit for purpose.”