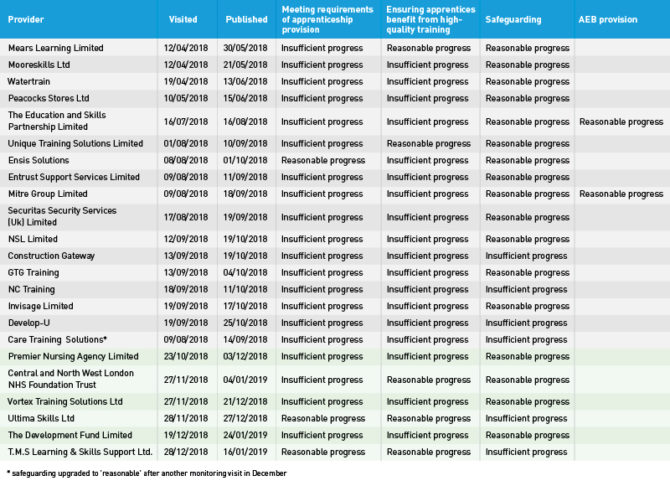

Six more providers have received temporary bans on recruiting apprentices as Ofsted continues its scrutiny of new provision, with four others now completely removed from the approved register.

The inspectorate is monitoring all new apprenticeship providers, and any deemed to be making ‘insufficient’ progress in at least one area faces being suspended from taking on new apprentices by the government unless there are “extenuating circumstances”.

The Education and Skills Funding Agency updated the register of apprenticeship training providers on Wednesday, which shows there are a total of 23 providers currently on the barred list.

Added to the list are: Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust, Premier Nursing Agency, T.M.S Learning and Skills Support, The Development Fund, Ultima Skills and Vortex Training Solutions.

They will now be prevented from recruiting apprentices until they have received a full Ofsted inspection and been awarded at least a grade three for apprenticeship provision.

A total of four providers have now been fully removed from the government’s apprenticeship provider register since Ofsted began its early monitoring visits in February last year.

The Key6 Group was one of the first to receive an ‘insufficient’ monitoring report, which was published in March last year, but the ESFA lifted the ban after two months when it was found to be making ‘significant’ progress in safeguarding and provided a “robust improvement plan”.

But, in a further twist, the Liverpool-based provider has now been entirely removed from the register. FE Week has been unable to contact Key6 to find out why it has been removed despite multiple attempts.

Premier People Solutions, a cabinet office-approved apprenticeship provider to government departments, has also been removed from the register of apprenticeship training providers following a damning monitoring report in November.

Kashmir Youth Project, which received two of the low ratings, has been removed, as has AMS Nationwide which went bust after Ofsted gave it two ‘insufficient’ ratings and the ESFA found it was claiming payments “incorrectly”.

ESFA guidance on monitoring visits, published in August, states that the agency will not remove an organisation from the register after a monitoring visit unless Ofsted has raised concerns about safeguarding and “identified a significant risk to apprentices”.

Removal from the register ends all current and future apprenticeship delivery, and means all apprentices must be moved to other providers.

However, if the provider was only found to be making ‘insufficient’ progress in its safeguarding, it can be reinspected and will have the restrictions removed on it if safeguarding has improved.

This was the case for N-Gaged Training and Recruitment, which was stopped from recruiting after its safeguarding was criticised in a report published in August. However, this was reversed after a reinspection in November found its safeguarding to be ‘reasonable’.