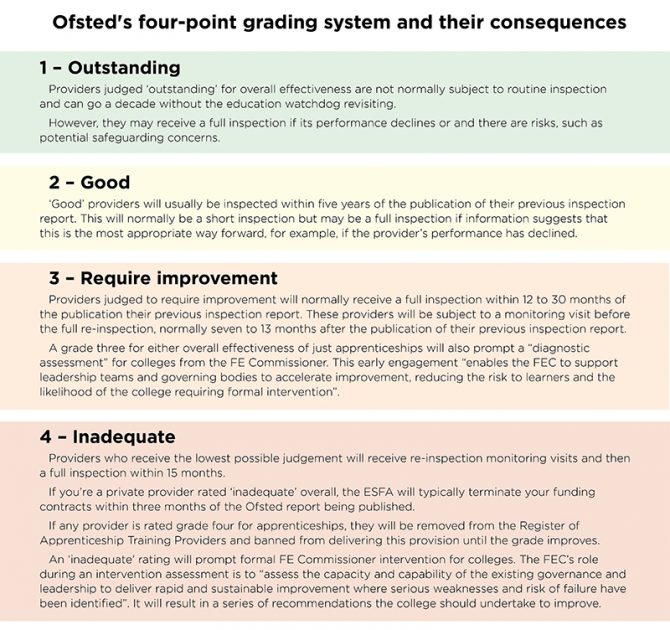

Three struggling colleges have been hit with a notice to improve by the government this afternoon, after they were all assessed to have “inadequate” financial health.

Both Hadlow College and West Kent and Ashford College, which together make up the Hadlow Group and have hit the headlines in recent months, received the warnings as they are currently reliant on exceptional financial support to survive.

Hartlepool College received its notice following an ESFA review of their 2017/18 accounts.

Colleges subject to financial notices to improve are put into FE Commissioner intervention and must run most spending decisions past the government.

The commissioner’s team began intervening at Hadlow and WKAC earlier this year following allegations of financial mismanagement.

It has been alleged the group’s former deputy chief executive, Mark Lumson-Taylor, forged emails from the ESFA to justify additional funding from the government.

When the ESFA checked those emails against their own server, they could find no record of them and the agency demanded the money back.

Hadlow Group has embarked on a number of failed business ventures in recent years that had left it in a financially precarious position.

This, combined with a failed application for £20 million from the ESFA transactions unit and the ESFA’s demands for funding to be returned, has left the college group reliant on government bailouts for survival.

Lumsdon-Taylor, several governors and the principal of both colleges Paul Hannan, quit following the FE Commissioner’s intervention.

The notice to WKAC supersedes one issued when it was part of K College in 2012, which came only two years before K College collapsed and Hadlow College adopted its West Kent and Ashford campuses, forming WKAC and the Hadlow Group.

Hartlepool College generated a deficit of £841,000 in 2017/18, has net liabilities of £2.7 million, an operating cash outflow of £230,000, and was subject to an FE Commissioner diagnostic assessment in May 2018.

It has also been borrowing in 2017/18 for the development of a new campus on Stockton Street in Hartlepool.

The college admits its accounts indicate “there may be a deterioration in the college’s unmoderated financial health grade,” but states the college is still a going concern.

This is because its three-year forecasts indicate a return to profitability, sufficient cash to meet its debts, and an ability to meet its covenants.

Despite this though, the notice means Hartlepool had to prepare a draft financial recovery plan by 29 April, following the issuing of the notice on 3 April; must provide the ESFA with monthly management accounts; and allow the ESFA to attend governors’ meetings.

The notice on Hartlepool will be lifted when its financial health grade has improved from ‘inadequate’ to at least ‘satisfactory’.

Among the conditions listed in the notice to WKAC, the college must submit all monthly individualised learner record (ILR) returns for all funding streams, for the remainder of the 2018/19 academic year as well as submit monthly management accounts to the ESFA and invite the agency to its governors’ meetings.

The notice does not specify what conditions must be met before it is lifted.

Nor does the notice for Hadlow College, which must also submit its ILR returns, its monthly management accounts and allow the ESFA to attend governors’ meetings.