Training providers were handed less than £9 million as part of a relief scheme to support adult education courses and non-levy apprenticeships during the pandemic – a fraction of the £144 million first projected to be needed.

Two rounds of supplier relief schemes were launched by the Department for Education in 2020 to retain provider capacity within the apprenticeships and adult education sector as Covid-19 and associated lockdowns put jobs and their financial viability in jeopardy.

But as previously reported by FE Week, strict eligibility criteria and the onerous nature of what could be applied for put thousands off submitting bids, while other cash-strapped providers, such as Bradford College, which nearly went into administration in 2019, had their applications rejected. Apprenticeships funded by levy-payers were also excluded, which wiped out any potential bids from more than 1,000 providers.

A National Audit Office “cost-tracker” for the pandemic showed the DfE had first projected a cost of £144 million for the adult education and non-levy apprenticeship relief scheme – but this dropped to £27 million by August 13, 2020.

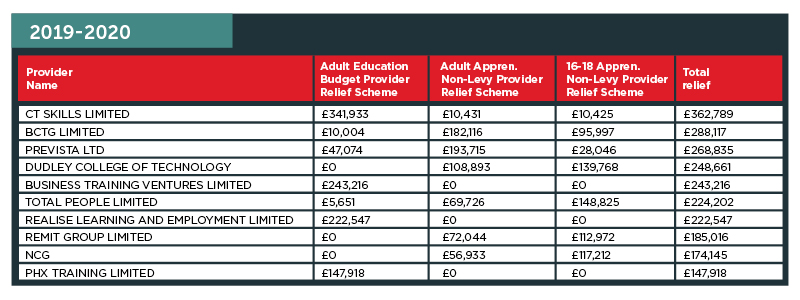

Final funding allocations for providers in 2019/20 and 2020/21 were published this week and revealed, for the first time, how much relief funding was distributed.

FE Week analysis of the data shows that 94 providers received a combined total of £5.7 million in 2019/20. Allocations ranged from £362,789 for CT Skills Ltd to £138 for Bridgwater and Taunton College.

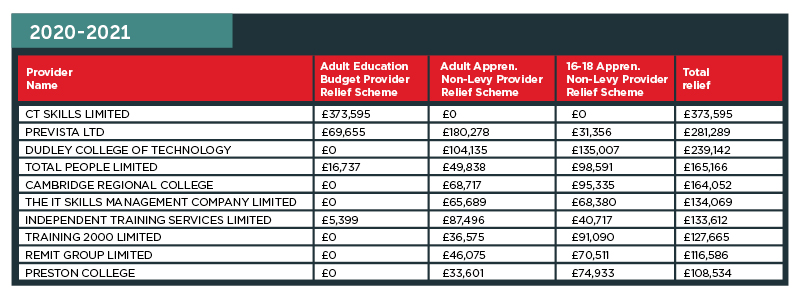

And in 2020/21 there was 62 providers that shared £3.2 million from the relief scheme. CT Skills Ltd again received the most – £373,595 – while Maritime and Engineering College North West received the lowest – £223.

Under the terms of the relief scheme, providers needed to demonstrate that they had a real “need” for the funding requested, including by evidencing low reserves, “in order to maintain capacity within their organisations to support learners and respond to the economic recovery”.

Providers also had to be prepared to provide “all evidence of spend for future reconciliation and provide ‘open book’ access to accounting records”.

Karen Woodward, the ESFA’s deputy director for employer relations, told a previous FE Week webinar that many providers failed in their bids because they struggled to “prove need” for the financial support and not many eligible providers applied because they did not feel “comfortable” in sharing the financial information that was being requested by the agency.

But those that were successful in receiving a slice of the funding have spoken about how “incredibly helpful” the support was in retaining staff and continuing delivery of training.

Dudley College of Technology was the college that received the most from the scheme – £248,661 in 2019/20 and £239,142 in 2020/21. Principal Neil Thomas told FE Week: “The funding allowed us to retain skilled specialist staff, who we may otherwise have had to make redundant, at a time when millions of apprentices across the country were placed on furlough, and businesses’ attention was focused on economic survival.”

He added: “The funding was incredibly helpful. The college’s income fell dramatically during the pandemic period due to a drop-off in apprenticeship starts, commercial work, international and adult education – none of which was protected for us. The college had to undergo a round of efficiencies and reduce staff and provision in the areas most affected.

“Support funding allowed us to protect some of the most critical apprenticeship provision in engineering and construction. Without it we would have had to make further efficiencies and reduce provision further. The funding allowed us to protect provision, so we could quickly gear back up when apprentices returned to the workplace and employers had the confidence to invest in training once again.”

And a spokesperson for Total People, which received £224,202 in 2019/20 and £165,166 in 2020/21, said: “At a time when apprenticeships were disrupted during the height of the pandemic, the relief fund enabled us to continue delivery, providing additional specific support to learners with a focus on wellbeing and welfare, especially for learners who were furloughed for long periods of time.

“It also meant that, as lockdown eased, Total People had the capacity to restart its provision as quickly as it could, enabling people to develop the skills they needed and supporting companies in upskilling their staff.”