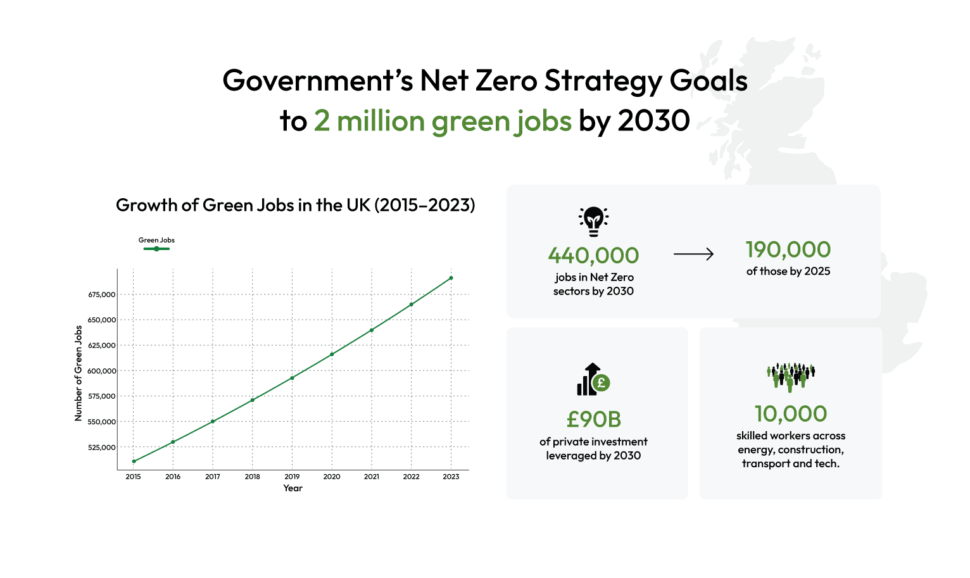

The government’s first “jobs plan” has been published, setting out how it hopes to supply the clean energy sector with hundreds of thousands more trained workers in the next five years.

It is the first of a series of plans expected to set out how the government and employers will invest in training for “British workers” to bring down immigration and grow priority sectors.

Civil service “experts” have been tasked with producing jobs plans for each of the government’s priority sectors, setting out what “actions” will be taken to meet forecast demand for jobs.

A range of new and existing actions on skills are in the 81-page ‘clean energy jobs plan: creating a new generation of good jobs to deliver energy security’, published by the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) earlier this week.

The plan forecasts that across the UK, jobs in the ‘clean energy’ sector will grow from around 440,000 in 2023 to 860,000 by 2030. This includes 31 priority occupations such as those in skilled construction, metal and electronic trades, as well as higher qualified engineers and machine operatives.

Energy Secretary Ed Miliband said: “Our plans will help create an economy in which there is no need to leave your hometown just to find a decent job.

“Thanks to this government’s commitment to clean energy, a generation of young people in our industrial heartlands can have well-paid secure jobs, from plumbers to electricians and welders.”

But any business investment?

While the clean energy jobs plan refers to large industrial investments that are expected to generate tens of thousands of new jobs, it contains limited details of new skills investments by businesses.

This is despite citing evidence of “significant underinvestment” in skills by employers in recent years and pledges in the new post-16 education and skills white paper to help businesses “invest further” in skills pipelines.

Addressing this, the plan says it aims to set “clear expectations” and create the “certainty” that industry needs to invest in skills.

Millions for more engineers

Announced in the industrial strategy this summer, the government has earmarked £182 million across the next four years to address engineering skills needs.

This includes £47 million to fund “engineering skills for adults”, £2 million to increase the number of engineering T Levels offered and £8 million in capital funding for clean energy engineering courses at levels 4 and 5.

Some of this funding will also go towards five new clean energy technical excellence colleges (TECs), with delivery expected to begin from April next year.

However, details of exactly how much funding is available for the new TECs are yet to be confirmed.

Build on what we’ve got

The UK and Scottish governments have also announced up to £20 million in funding to help North Sea oil and gas workers transition to “new roles”. This will extend a £1 million scheme, launched this year, until 2028-29.

Regional skills pilots in Cheshire West and Chester and North and North-East Lincolnshire will receive up to £2.5 million for “innovative” schemes to support workers “moving into clean energy”.

An existing energy skills passport scheme run by industry bodies RenewableUK and Offshore Energies UK will also be expanded to help workers in more roles move from “carbon-intensive industries” to clean energy sectors.

Veterans and prison leavers

A 12-month pilot led by Mission Renewable will connect veterans and service leavers with clean energy careers in the east of England, which the government hopes to learn from to “strengthen veteran pathways” across the UK.

The government also plans to prototype “innovative training and job-matching approaches” for non-violent offenders in regions with “critical energy sector vacancies”.

Keep coordinating

DESNZ has established a minister-led “steering group” to support joined-up implementation across the UK, “regular discussions” with trade union general secretaries, and “wider stakeholder engagement” on “specific themes”.

Both industry and government bodies such as the Careers and Enterprise Company have also committed to promoting clean energy careers, including through a UK-wide “awareness and attraction campaign” and engagement with young people.

DESNZ promises to “monitor clean energy jobs and skills trends” and provide “regular updates” on the progress of its jobs plan actions.