Large and small businesses should receive the same level of government subsidy for apprenticeship training, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

Experts at the economic research organisation have also warned that Labour’s plan to reform the apprenticeship levy so that it funds other types of training risks creating “significant deadweight costs”, in a new report published today.

The apprenticeship levy, introduced in 2017, subsidises apprenticeship training costs. Firms that pay the levy – those with an annual pay bill of more than £3 million – get a larger subsidy rate of 110 per cent. Non-levy payers meanwhile get 95 per cent of apprenticeship costs covered.

Handing larger firms a large subsidy could risk companies using apprenticeships because they are funded, even if their needs are better suited to other training schemes.

Imran Tahir, author of the report and research economist at the IFS, said that introducing a lower but uniform subsidy rate would “create a simpler and more coherent system, and one that better ensures employers invest in the right form of training”.

His report said: “While there is a case for subsidy rates being set according to the degree to which training is likely to be underprovided, this would be complicated and difficult to measure and implement in practice, so a uniform rate is desirable.

“The uniform subsidy rate should also be set at a lower level than the current rates which effectively subsidise the full cost of apprenticeship training.”

Speaking at a launch event for the report, Tahir suggested the subsidy rate could then be increased “to target young people or certain industries where there are particular needs, to increase the level of apprenticeship training”. But he reiterated that all subsidy rates should initially be universal.

‘Significant deadweight costs’

The IFS also criticised the Labour Party’s pledge to reform the apprenticeship levy into a growth and skills levy if it wins the next election. That proposal, made last September and reiterated in this week’s Labour party conference, will mean employers could use levy funding for non-apprenticeship training.

But the IFS warned this risks “significant deadweight costs” because it could end up subsidising training that would have taken place without anyway like past schemes such as Train to Gain in late 2000s.

Train to Gain was dropped in 2010 after the National Audit Office found half of employers who got training subsidised via the scheme would have paid for it themselves.

Tahir also warned an expanded growth and skills levy could subsidise “unproductive training at the cost of potentially more valuable apprenticeship training”.

The Labour party was approached for comment.

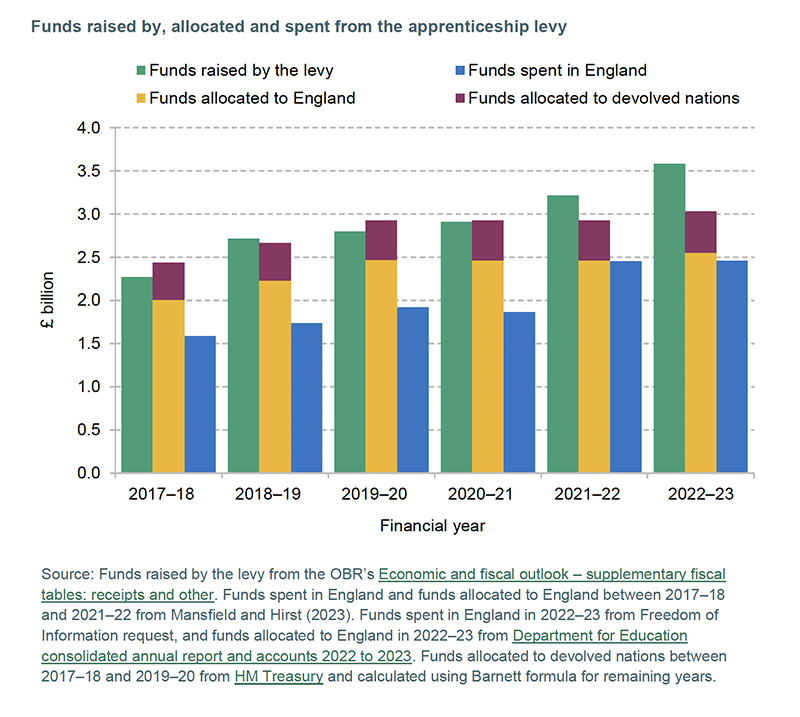

Tahir’s report pointed out that over £500 million raised through the apprenticeship levy has gone unallocated by the Treasury for spending on skills and training since its launch in 2017, as FE Week reported last month in the absence of transparency data from the Treasury. The IFS was able to use the Barnett formula for its calculations, so shows slightly higher amounts of unallocated funding.

Other key findings from Tahir’s report included that the number of publicly funded qualifications started by adults has declined by 70 per cent since the early 2000s, dropping from nearly 5.5 million qualifications to 1.5 million by 2020.

Public funding for adult skills is set to increase by 11 per cent from £4.3 billion today to around £4.7 billion by 2024–25. The IFS said that given the “low returns to many adult skills courses”, rather than expand the range of courses available, the government should increase existing funding rates.

Tahir said: “Adult skills policy is not a simple area, nor one that is easy to ‘solve’. History shows us that spending and setting qualification targets are not enough. What matters is ensuring that individuals and employers have the capacity and incentives to invest in additional education that builds valuable skills.”

A spokesperson for the Department for Education said the department is investing “an additional £3.8 billion in skills” this parliament, and is replacing low quality qualifications “with those that better meet the needs of employers”, including apprenticeships and skills bootcamps.

“The apprenticeship levy has helped us to create sustainable funding that incentivises employers to invest in high-quality apprenticeship training,” they added. “It has also enabled us to increase investment in apprenticeships to £2.7bn, helping businesses of all sizes to benefit from apprenticeships.”