ESresultsbanner

EuroSkills 2014 competitions come to an end — awards await

Day three at Lille brought with it the promise of the final break to the rigorous and testing competitions.

From pretty early on Saturday, the happy din of cheering as the young competitors ended their tasks drifted around the Grand Palais venue every half hour or so.

Timing it well, it was possible to stand next to a skill stand and count down the clock to completion before national flags were draped over competitors Olympics-style — and rightly so.

I was lucky enough to have a schedule that meant I was at most of the Team UK finishing lines, ready to interview.

Speaking to the majority of them, it felt a little like catching a rabbit in the headlights before the media training they’d enjoyed as part of the EuroSkills journey kicked-in.

For sure, some were naturals, while for others it probably felt more of a chore, but from my end it felt just as much a privilege to speak to these young men and women — fresh from being put through their paces — as any actor, politician and sportsman or woman I’ve interviewed.

But the one thing that came through in speaking to them all was a sense of relief, not so much that their competition had ended, but of a wider sense of accomplishment.

So, as we head into the last day, with the judging, awards and closing ceremony all that’s left of EuroSkills 2014, it’s right that such sentiment be something all competitors take away.

Medals tomorrow night? Great. But achievement through simply being here and thereby raising skill levels is the ultimate aim.

Pictured from left: Team UK florists Zoe Rowlinson, Warwickshire College, and Louisa Cooper, South Staffordsire College, both aged 20, after finishing their joint competition

Challenging first day for Team UK at Lille EuroSkills

The massive hall of the Grand Palais in Lille where the skills competitions take place feels like a cross between an workshop, a zoo and a stage set, with temporary restaurants, florists, shop windows and half decorating walls, all open to the pubic gaze.

It’s noisy, it’s busy and its crowded, and at the centre of it all, the competitors remain impressively oblivious to it all, concentrating entirely on their work.

Still, opening day of your first international level competition must be a nerve-racking experience.

After weeks and months of trainers and coaches supporting you every step of the way, the moment when you suddenly find yourself alone in an arena, faced only with the tools of your trade and a tough specification must be difficult to prepare yourself for.

But it’s how competitors handle that moment, and the one after that, which team UK selectors and training managers will have been looking at yesterday.

I know I keep saying it, but these young people are incredibly skilled – and not just in terms of their practical ability.

The trainers prowling around competition areas won’t just be looking for who has the best technical skills, they’ll also have been keeping an eye out for who is coping with the pressure – who realises they’ve made a mistake, stays calm and corrects it, and who just crumbles?

Some competitors will have been chosen because they handle that pressure well, some will have been chosen because they need just a little bit more practice.

After the first day of competitions the mood among competitors is mixed.

John Peerless and Calum Knott, the mechatronics team, have been told they’ve scored highly for the day and despite facing her two worst test areas, beauty therapist Rianne Chester was confident that she’s finished the day towards the top of the table.

The visual merchandising team were less jubilant – after a shaky start, Jasmine Field told me, they pulled it back, only to realise they’d missed a crucial detail at the last minute.

Team-mate Catherine Abbott said: “We’re a bit disappointed, it didn’t go as well as it could have done. We weren’t on form and it just slowed down the whole day.”

But, despite the setback, the two were looking on the bright side and clearly know better than to let it throw them completely off balance.

“We’ve still got two days of competition so we can get it back,” said Catherine. Jasmine agreed. “We’ve still got still 70 per cent of marks to get back even if we do lose a couple today,” she said.

According to mechnical engineering computer-aided design competitor Andrew Beel the attitude they’re able to have to mishaps and move on is all down to the training and support.

A fault in the machinery he was working with created problems for him during the day.

“I ended up stepping back, chilling out a wee bit and coming back to it,” he said. “Since I’ve been involved with WorldSkills, my maturity has increased so much – I wouldn’t have handled today like that at all before. I’d have thrown my keyboard off the table and walked out.”

However yesterday went, all the competitors are putting it to one side and approaching today as a whole new challenge – which, given the circumstances, is a pretty impressive skill in itself.

But, as Catherine and Jasmine made clear, there’s still everything to play for.

Edition 113: Peter Roberts, Dr Shaid Mahmood and Neil McLean

It will be all change at the top for Leeds City College this year with the retirement of principal Peter Roberts and a new governors’ chair already in post from Wednesday (October 1).

Mr Roberts, a father-of-two and chair of the 157 Group, revealed to college staff his intention to call it a day late last month.

He said: “I turn 60 over the course of this academic year and have decided to retire

next summer.

“To cut a long story short, I have worked in the education sector for some 37 years, and been in FE since 1983.

“I have somehow managed to be in senior management for over 20 years and have been a principal/chief executive since 2002. It is simply ‘my time’.”

He said that no timescale had been set for his replacement to be in post, but that interviews were expected to take place after Christmas with a successor in post near

the end of the current academic year —

when he retires.

Neil McLean, who has been chair of the college board since 2009, has stepped down, but continues as a board member until

the expiry of his term of office in April

next year.

Dr Shaid Mahmood (former vice chair) became the new chair of Leeds City College from the start of this month.

“I am sure that this will be an excellent appointment although Neil will be a very hard act to follow and has been superb as chair,” said Mr Roberts, who started in FE as a lecturer in leisure and recreation at Sheffield’s Stannington College.

Mr Roberts has also worked at Selby College and in 1992 became vice-principal of Rotherham Sixth Form College and later York College. In 1997 he moved as principal to Stockport College before moving, as principal, to Leeds City College in 2009.

“Mr Roberts has led Leeds City College through a period of rapid change and development in the past five years, doing so with tremendous energy and dedication and establishing it as one of the largest and successful FE groups in the country,” said Dr Mahmood

“His retirement after some 37 years — many of them in leadership roles — is thoroughly well deserved. His successor will have a fantastic opportunity to further shape and lead an exciting, vibrant and forward looking college.”

Mr Roberts will step down as 157 Group chair in November, having served in the

post for two years, with the election of a

new chair.

Maths proposals add up to a funding change

The charity National Numeracy has launched a manifesto aimed at eliminating the “national scourge” of poor everyday maths skills among the UK population. Wendy Jones explains how it wants to improve adult numeracy.

‘Poor numeracy is a massive challenge for the UK and the arguments for change are overwhelming’ — these were the blunt opening words of National Numeracy’s Manifesto for a numerate UK.

Successive government have failed to make any real difference to adult numeracy. There have been some improvements in literacy — according to the Skills for Life survey a couple of years ago — but numeracy, with a lower starting point,

has got worse.

Half of adults in England have the numeracy skills roughly expected of primary school children (the adult/child comparison offers very crude linkage, of course) and more than three quarters don’t have skills equivalent to those needed for a C grade

at GCSE.

This was the context for our manifesto. A lot of our emphasis is necessarily and controversially on school maths, since that’s where it starts to go wrong for many people.

We want a new and separate focus on numeracy as a discipline that underpins every subject, leading to an additional GCSE in numeracy or core maths. That clearly has implications for the FE sector.

But it’s the thinking on adult numeracy that I’d like to concentrate on. Formal adult maths or numeracy provision has a history of neglect — of being under-valued, under-funded and under-researched.

And even though there clearly are pockets of excellence and successful innovation, the Skills for Life results suggest there has been no scaling up of good practice. We therefore would like to propose some radical cross-sector measures.

First, take the adult numeracy curriculum. We want to remove the ‘tick box’ approach which simply goes through the various skills and processes with no sense of inter-connectedness and no apparent overall goal.

We would replace this with a new model, based on the Essentials of Numeracy developed by National Numeracy in partnership with a group of maths curriculum experts. This links the different areas of knowledge and understanding to the very concept of being numerate, that is, being able to use maths to solve everyday problems, make decisions and reason, knowing which maths to use and being ready to try different approaches.

We also propose a change in the way adult numeracy is assessed and courses funded.

Providers should not be rewarded simply on the basis of the qualifications achieved — this encourages a focus on low-hanging fruit and discourages efforts with the most challenging students.

Instead, account should be taken of the student’s starting point and the progress made — the distance travelled. This is particularly important in maths where many start from a very low base and where real achievement may go unrecognised.

It’s an approach we work into our own National Numeracy Challenge, which encourages adults to improve their skills online and measures the progress they make.

We have purposefully not attempted to cost our proposals. Such costings are often wide of the mark and give politicians an immediate excuse to sideline ideas. Nor have we commented on the cut in the adult skills budget or looked at the workforce issue — we leave that to others.

Costings are often wide of the mark and give politicians an immediate excuse to sideline ideas

Instead, we major on the fundamental change in attitudes needed if the UK is to become numerate. We propose a new drive to spread the positive messages that numeracy is an essential life skill, that it can be learned and that dismissive attitudes

are harmful.

We also want to see more research into how people can be persuaded to improve their skills and develop resilience and persistence (we’re already working on this with the Behavioural Insights Team — the ‘Nudge Unit’ started in the Cabinet Office).

It is a matter of changing beliefs and behaviour — and removing the structural barriers that currently get in the way. We know that’s a huge task — but we need to start on it now.

Conservatives Conference: No new cash behind citizen service pledge

Prime Minister David Cameron’s plan for guaranteed access to the National Citizen Service will not be backed up with extra funding, the Conservative Party has conceded.

In his speech to the Tory Party conference in Birmingham, he pledged to guarantee a place on the holiday learning scheme for every 16 and 17-year-old in England were he to win the General Election next year.

But Mr Cameron’s party later conceded that the money for the expansion of the project would have to be found from within existing budgets, and that it had only planned for attendance figures up to 150,000 in 2016, the same number budgeted-for in 2015.

During his speech, Mr Cameron said: “I want a country where young people aren’t endlessly thinking: ‘what can I say in 140 characters?’ but ‘what does my character say about me?’

“That’s why I’m so proud of National Citizen Service. Every summer, thousands of young people are coming together to volunteer and serve their community.

“We started this. People come up to me on the street and say all sorts of things — believe me all sorts of things — but one thing I hear a lot is parents saying ‘thank you for what this has done for my child’.

“I want this to become a rite of passage for all teenagers in our country, so I can tell you this: the next Conservative Government will guarantee a place on National Citizen Service for every teenager in our country.”

However, a Conservative spokesperson later told FE Week: “All 16 and 17-year-olds will be guaranteed a place on National Citizen Service.

“This commitment will be met from existing budgets — 40,000 people took part in National Citizen Service in 2013 and we have already made funding available for up to 150,000 places in 2016.”

By FE Week calculations, based on an estimated cost of £1,000 per learner, put the cost of extending the service to 150,000 teenagers at £150m, but Conservative HQ would not confirm how much it was preparing to set aside, or which department’s budget the cash would come from. It is currently funded directly by the Treasury.

The National Citizen Service was piloted in 2011 and involves groups of teenagers going on trips from a few days up to three weeks, generally involving some kind of outdoor activities, team-building and community work.

Mr Cameron’s pledge was welcomed by Skills Minister Nick Boles, who said that the widening of participation in the scheme would be gradual over the course of the next Parliament.

He said: “I think [the Prime Minister] said by the end of the next Parliament, so it’s 2020 not 2016.

“The biggest provider is an organisation called The Challenge, which I set up before the election to really test the concept, and it’s a fantastic programme.

“I actually think it’s going to end up being a fantastic source of careers advice and guidance, because one of the things it involves is young people taking on projects in their local community in teams, and that can be with local businesses or local charities so, it does create a great opportunity for people to get to young people at a key decision point in their lives.

“I think you won’t get more detail until the manifesto, and I suspect in the manifesto you will get a fairly broad idea that this is how it is and by 2020 all teenagers will be able to do it. Currently it is fully-funded by the Chancellor. There is a question mark over whether there are other sources of funding one could pull in to come alongside taxpayer funding.”

It comes after Education Secretary Nicky Morgan used her speech to the conference on Tuesday to call for businesses and schools to work more closely together to improve careers advice.

Despite earlier indications by Mr Boles that careers advice would feature prominently, Ms Morgan’s speech contained no policy announcement on the subject.

Instead, she said that careers, “for too long overlooked in schools”, were now essential.

She added: “Let’s make work experience something of value, something that opens people’s eyes to the possibilities of the world of work, something that helps them aspire to more.

“And let’s get businesses working closely with schools to help children make the right choices at the right time, choices that help them pursue the careers they want…careers that perhaps they had never thought of before.”

Mr Boles told FE Week: “Needless to say she’s a Secretary of State and I’m a humble minister so I didn’t actually know exactly what was going to be in her speech, but I know it’s an area she takes a very strong personal interest in and we have been in a number of meetings together about it.

“I suspect that there will be more to come, and presumably it was just a decision that conference wasn’t the right place to talk about it.

“I still don’t want to steal her thunder and go into much more detail, but I think the one thing it would be fair to say is that the thing we all recognise is that you need to have somebody in every school, whether they’re in there full-time or able to come and go quite often, who has a real understanding of all the choices in real life.”

David Cameron on FE and skills

* Selected quotes from the Conservative leader’s conference speech

With us, if you’re out of work, you will get unemployment benefit, but only if you go to the Job Centre, update your CV, attend interviews and accept the work you’re offered.

As I said: no more something-for-nothing.

And look at the results: 800,000 fewer people on the main out-of-work benefits.

In the next five years we’re going to go further.

You heard it this week – we won’t just aim to lower youth unemployment; we aim to abolish it.

We’ve made clear decisions.

We will reduce the benefits cap, and we will say to those 21 and under: no longer will you have the option of leaving school and going straight into a life on benefits.

You must earn or learn.

And we will help by funding three million apprenticeships.

Let’s say to our young people: a life on welfare is no life at all, instead, here’s some hope; here’s a chance to get on and make something of yourself.

What do our opponents have to say?

They have opposed every change to welfare we’ve made – and I expect they’ll oppose this too.

They sit there pontificating about poverty – yet they’re the ones who left a generation to rot on welfare.

‘More coherence on vocational education needed’

The government needs a more coherent strategy for vocational education, Education Select Committee chair Graham Stuart has said.

He joined a panel at a fringe event at the Conservative Party Conference organised by the National Institute of Adult Continuing Education, the Association of Colleges and 157 Group.

Speaking at the event, Mr Stuart said successive governments had failed to establish a clear policy on skills, adding that Professor Alison Wolf’s 2011 report on vocational education was the current government’s strongest point on the issue.

He also criticised Conservative peer Lord Baker, who has pioneered 14+ educational institutions such as University Technical Colleges (UTCs), for working at odds with former Education Secretary Michael Gove.

Mr Stuart said: “What we don’t have is a particularly structured approach to vocational educational pathways. Countries with much lower youth unemployment than us not only have the status thing but they have very clear routes and they work at them for years, but we keep tearing it up.

“In the last Parliament Ed Balls had a huge opportunity with the diploma, but his pig-headed stupidity in pushing it through before he’d got it right. We told him not to.”

He added: “Wolf report apart, there hasn’t been much coherence to this government’s strategy in this area.

“One thing is the choice — is it at 14 or 16? And countries differ. We haven’t really made a choice. Michael Gove quite clearly thought it should be 16, and yet there were these strange cuckoos in the nest, Ken Baker chief among them.

“In the same government, at the same time as you had Gove saying the best countries have the choice at 16, old Ken is setting up UTCs and now studio schools and the careers academies from 14. It’s a very peculiar thing.”

Earning or learning… or yearning for one more student?

I introduced myself on the FE Week website as the new FE Insider last month as having a real passion for nurturing young talent and then I overheard David Cameron during Party Conference season speaking on the Marr Show toward the end of last month.

And he ironically marred all of my aspirations for all of those hopeless, direction-less prospective students out there. Mr Cameron outlined that, should the Conservative Party win the next general election, all 18 to 21-year-olds would receive a “youth allowance” instead of being able to claim housing benefit or jobseeker’s allowance.

In order to continue receiving this new allowance after sixth months looking for work, claimants would have to accept an apprenticeship or traineeship…and failing that they would have to accept mandatory “community work”.

As we all probably know this is a tactic for lowering the unemployment figures, and some of the policies have merit to them although you could argue this feels to me like having the hours of a worker with the spending power of an unemployed person.

But let’s go back to basics. We are all ‘doing more for less’ again and in a marketing director’s perspective it’s ‘doing more with less’.

It’s all well and good addressing Britain’s ‘skills gap’ of which we know there’s a void between how qualified people are and how qualified they would ideally be for the needs of the economy via a youth allowance offering, but let’s go back to basics. How do we market what FE and other training providers offer to potential students, of any age?

We know we’ve got to get smart with our offer. It’s got to be flexible. It’s got to be technologically-advanced. It can’t be 9 to 5 and most importantly it has to fulfil the student and lead to job readiness

Gone are the days of bulky prospectuses. We all know these are used as doorstops by our competitors, and for fear of alienating myself any further I won’t name just which category this is.

And let’s not forget the other important point — it’s not environmentally friendly and the kids on the block want digital.

Marketing to prospective students has become an art of epic proportions. I’ve been lucky enough to observe this year’s recruitment battle at Stratford-upon-Avon College and have come out the other side enlightened and empowered to know what we need to do for next year, now.

And I only wish we could apply the auto-enrolment rules around pension to all of those students we’re waiting to snap up.

Surveys suggest that word of mouth and face-to-face contact with prospective students is most important, with mobile technologies and traditional marking coming next. I’m not sure I really care which ones are most important as I know that when catering to such a wide base of prospective students you have to hit home hard with all techniques.

But I come back to the Prime Minister’s vision. Enticing young people into earning or learning is difficult when the very basics are not put into place.

A college can offer the world, but when it’s nigh on impossible to travel within a reasonable time to your place of learning because the councils have cut back massively on public transport, no amount of social media marketing or jazzy website is going to get those students enrolled.

We need to continue to put the pressures on with the powers that be, and fast, if we are to help Mr Cameron reach his vision of zero unemployment and our dream of over-recruitment.

So we know we’ve got to get smart with our offer. It’s got to be flexible. It’s got to be technologically-advanced. It can’t be 9 to 5 and most importantly it has to fulfil the student and lead to job readiness.

Only then can we be sure that there’s earning or learning taking place. Otherwise it’ll be more groaning from us, or maybe

just me.

Paul Warner, director of employment and skills, AELP

“I remain convinced that anyone’s career is based on luck,” says Paul Warner, director of employment and skills at the Association of Employment and Learning Providers (AELP).

“You don’t realise how momentous a decision can be at any point until years later you go, ‘What if I’d made another choice? What would have happened?’

“So none of this was planned.”

As a teenager, Warner’s ambition in life was to become a fighter pilot following in the footsteps of his father, Len, who had been conscripted in the Second World War.

“He’s not sure if he was unlucky or not,” Warner tells me.

We were going to blend being Ultravox with The Stranglers — you can imagine how wonderful that was

“He was in training to fly bombers, and then just before he was going to go on his first mission, the war ended, so he was a bit annoyed.”

Instead, Len went into business, running a timber company near the New Forest, where Warner grew up. But the flying experience left a mark on his son, born 20 years after the war ended.

“He just used to tell me about it and I just always thought I wanted to be in the air force,” says 50-year-old Warner.

“I absolutely loved planes, so I thought it would be great.”

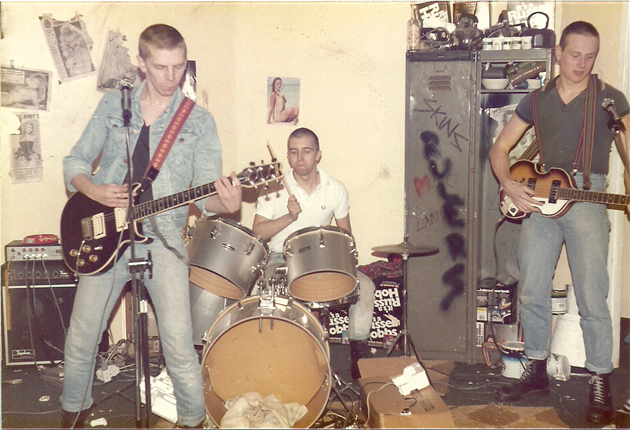

His other major ambition, he says, was to be “mega rock star”. He currently has a fully functioning recording studio in his house.

His musical inspiration is Gary Numan, who he’s seen perform more than 60 times and one of his proudest moments as a parent to 12-year-old Alex, he says, was when she asked to come with him to a Numan gig.

“I thought ‘my work here is done, I’ve brought her around to my way of thinking’,” he says.

Although he writes and records “whatever I can come out with,” Warner’s own musical career was scuppered by his flying ambitions.

“I was in a band as a teenager, during the big New Romantic phase in the early 1980s, so we decided we were going to blend being Ultravox with The Stranglers, you can imagine how wonderful that was,” he says.

“But I was going to be a fighter pilot. Rock star didn’t fit. You couldn’t be a fighter pilot part-time, it wasn’t part of the plan,” he says.

However, Warner “took a bit of a left-turn at the traffic lights” while studying international relations at Keele University.

“I met quite a lot of people who were in the forces there and it’s more than just flying planes, it’s a lifestyle, and I don’t think that lifestyle was for me,” he says.

He finished university with a first class degree, and “no-one was more surprised than me,” he says.

“Fortunately, on the day of my finals, there was a coup in Fiji. The finals were in the afternoon, so in the morning I spent the whole morning reading up on it so by the exam I knew all about it and it was very topical.”

After university, Warner admits he had “a big sort of gap, where I didn’t quite know what I was going to do”.

However, the pressure was on by that point, because while at university, Warner had started going out with a trainee teacher named Claire and, he says “it became blindingly obvious that I had met the love of my life”.

Having married, the couple moved in search of more teaching opportunities for Claire.

“I was doing alright in Birmingham. I was a top performer in Oxford, but I got to London and crashed and burned — I completely lost my mojo and couldn’t sell a thing,” he says.

Fortunately, he bumped into a former colleague who had moved to a company helping unemployed people into work.

“I thought, ‘That sounds interesting’, I didn’t even know companies like that existed. So, speculatively, I sent in a letter to TBG Learning and they took me on,” he says.

For Warner, one of the best aspects of his new role, he says, was realising, “actually,

these people need me”.

He remained at the company for nine years, leaving as the business development director in 2002 and after a “brief stint” running work-based learning at Barking College, joined AELP, or Alp, as it was then known.

“I was lucky enough to be at the end of the sort of fluffy days when there was lots of money floating about and nobody seemed to take a great deal of notice of what’s going on,” he says.

“The whole sector has been getting tougher, more commercial, more… ruthless? More clinical, for years it’s been going in that direction.

“I think it’s really good that we’ve increasingly seen less emphasis given to the type of institution that is delivering, so independents have a far bigger portfolio of things they can deliver.

“The trade-off is, if you don’t deliver, you go out of business.”

Independents have a far bigger portfolio of things they can deliver. The trade-off is, if you don’t deliver, you go out

of business

And in the current climate of budget cuts and reforms, he says, the role of AELP becomes more valuable.

“Stakes are quite high, particularly for independents, because their livelihood depends on whether or not they get it right,” says Warner.

“And that’s very worrying for them, so it’s nice to be a part of an organisation that can give a bit of an umbrella.

“Our membership’s increasing quite a lot, quite steadily, at the moment, and I’m pretty certain that it’s because it’s getting tougher. They need information, they want reassurance, and they need to know they’re not on their own.”

However, while the future may not be completely “rosy” he says, “it’s not necessarily a disaster” either.

“It is a very difficult situation and it’s an increasingly small tightrope to walk along,” he says.

“But as long as we keep moving towards a level playing field of funding being available for quality delivery, it doesn’t matter what type of institution, just are you any good at it. Is what you’re doing worthwhile? Is it achieving some objectives?

“There’s still a bit of a way to go at the moment bit if we can really get to that, the skills system will be in a pretty good place.”

What’s your favourite book?

Usually whatever I’m reading at the moment. Right now it’s The Nazis: A Warning From History, by Laurence Rees

How do you switch off from work?

Music, both playing and listening. I listen to a lot of squawky electronic music I write whatever I can come out with and it’s only for my own benefit, though I do inflict it on my wife and daughter

If you could have anyone to a dinner party, living or dead, who would it be?

Eddie Izzard, Graham Norton and Brian Cox. I think that would be really intelligent and very, very funny. I’ll get my wife to cook because she’s very good at that

What’s your pet hate?

I really hate lazy English. I hate people who say things like, “Do you know what I mean?” or, “And stuff.” No, I don’t know what you mean. That’s the whole point of you talking to me — you’re supposed to tell me. Lazy English just offends me because there’s no need for it

What did you want to be when you grew up?

A fighter pilot