The National Extension College (NEC) has pioneered distance and second-chance education for six decades this August, and its founding mission is more relevant than ever, writes Sir Alan Tuckett

Organisations focusing on second-chance education for adults have had a tough time these last twenty years, as more than four million publicly funded places for adults in further education have been cut since 2010 as a result of funding changes.

In the open and distance learning field there has been a litany of failed government initiatives to create a sub-degree equivalent of the Open University – among them the Open Tech, the Open College, the University for Industry and the NHS University.

All short-lived, all suffering from the sudden shifts that have characterised post-school lifelong learning policy in recent decades.

Yet as the Covid pandemic highlighted, distance learning is of key importance for people unable to leave home for whatever reason.

For that reason alone, it is worth celebrating the sixtieth birthday this month of the National Extension College (NEC), and to use the occasion to argue for an overhaul of policy thinking on the field, to recognise its place in addressing social disadvantage, and in levelling up education opportunities in Britain.

The NEC is small, innovative, independent of government funding, yet committed to the public good. It was the brainchild of the social entrepreneur Michael Young, and his colleague Brian Jackson, who became the college’s first director.

Pioneering distance learning

Young recognised that many people who had missed out on much of their education the first time around because of the second world war and passages of ill health, and those with work or family commitments, would welcome a second chance to learn and to gain qualifications.

He believed there needed to be an opportunity to enable them to learn in their own time, and at their own pace. Young argued, “We were searching for education without institution, learning while earning, courses which people of all ages could take in their own time, at their own pace.”

NEC’s start was modest. Supported by a grant of £16,000 from the Gulbenkian Foundation and £1,000 from The Guardian, its initial range of programmes in 1963 included O level mathematics and English, university courses, mounted in partnership with the University of London’s external course programme, and a range of vocational programmes.

An early media partnership with Anglia Television introduced new approaches to learning maths and English, just as later the NEC partnered with the BBC in offering early computer literacy courses. Its early experiences shaped the Open University which opened to students in 1971.

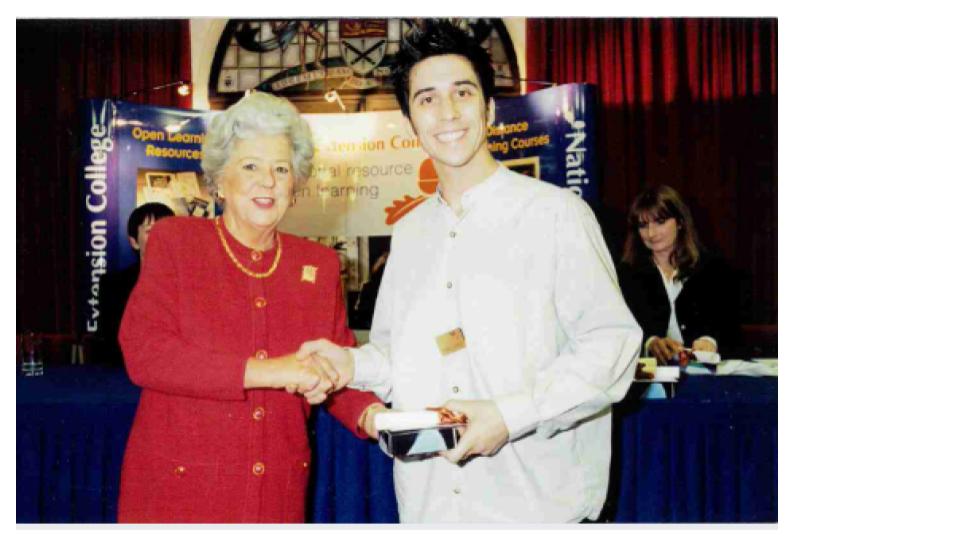

Among the college’s alumni was Eddie the Eagle (Michael Edwards), immortalised in film for his exploits on the ski slopes at the 1988 Winter Olympics. In the 1990s Eddie took a range of O and A level courses through the NEC before going on to a degree at De Montfort University. The comedian Russell Kane studied A level sociology at the NEC and now sponsors student scholarships.

By 1988 the College had provided comparable course opportunities to more than 250,000 people – a figure more than tripled now.

Saved from disaster

Growing demand saw a steady growth in staff support to some 70 people in 2002, and through the 1990s and the first decade of this century, NEC managed the transition from a paper and post service to online delivery.

But in the years leading up to 2010, it suffered several years of financial losses which prompted its board of trustees to seek a merger.

They opted to join with the Learning and Skills Network (LSN), which sold off NEC’s prime location in Cambridge for £6 million. But in a matter of weeks, the LSN itself went into administration in 2011.

The original NEC charity had been dissolved at the time of the merger, but, convinced of the critically important role the college played in its students’ lives, Ros Morpeth set about resuscitating it.

Morpeth led NEC from 1988 to 2003 and maintained an active engagement thereafter. With colleagues she found a dormant charity, the Open School Trust (another of Michael Young’s creations), and put a successful bid to the administrators, PwC, to take the National Extension College out of administration, with support from the National Institute of Adult Continuing Education (NIACE) and the Open University.

Morpeth’s success in re-establishing the NEC, which she ran again for several years without remuneration, was recognised when she was voted FE leader of the year in the 2016 TES FE awards.

As the college celebrates its birthday in robust health under the leadership of Esther Chesterman, and prepares for its next sixty years, it looks to engage artificial intelligence for its potential benefits to personalise the learning process, while being aware of the risks it brings.

There is no doubt that its original remit – to offer second chances to learners in our educationally divided country – is as relevant as ever. And any lifelong learning policy worth having must surely find an effective way of supporting institutions and provision dedicated to those ends.

Good to hear of NEC’s continued success.