The stereotypical picture of an accountant, says Mark Farrar, chief executive of the Association of Accounting Technicians (AAT), is “a desperate image of a white bloke in a pinstripe suit hunched over a great ledger or a spreadsheet”.

But that is “a million miles away” from the truth about financial management, he says as we sit in AAT’s airy, open-plan office surrounds, which he tells me were chosen specifically to dispel the myths that accountancy is closed-off and obscure.

“The image of a sector can be very important to attracting people to it and that’s a harder fight these days because all sectors are looking for the best,” admits the 53-year-old.

Farrar’s own career beginnings are probably a long way from most people’s idea of a typical accountant.

Born in Dublin, Farrar grew up in Bangor, Northern Ireland, where he harboured dreams of joining the Royal Navy — a choice which “would have been controversial if you’d announced it loudly,” he says with a wry laugh.

“It perhaps wasn’t the most usual of choices — and for a southern Irish guy as well.

“But it was something I wanted to do and I wasn’t going to let anything stand in my way.”

Growing up in Northern Ireland in the 1960s and early 1970s meant “you gained a good dose of common sense and street wisdom very quickly,” explains the father-of-four.

“But, actually, it was safe,” he adds.

“The headlines in some ways transcended the reality because actually The Troubles were in isolated areas most of the time — I grew up by the beach in a pleasant place and to this day I value the experience I had.”

The Navy sponsored Farrar through a degree in oceanography at Swansea University, so he joined the so-called brain drain leaving Northern Ireland at the time.

“I was always fairly independent,” he says. “I’m the one who picked myself up and moved over here to go to university and never went back — something that was fairly common at the time.

“One of the jokes was that on one of the signs at the Rosslare ferry terminal, someone had spray painted ‘Last one out, turn off the lights’.”

After university, where “the rugby was good, the beer ok and the people great,” Farrar joined the Navy full time, generally finding himself in the north Atlantic and the North Sea, while friends found themselves deployed to sunnier climes in Asia and the Caribbean.

After a few years, Farrar set a course for dry land, and set his sights on accountancy, training with Deloitte Haskins and Sells in Southampton, having discovered a love for the south coast of England.

However, at the time accountancy was a means to an end.

“From the beginning I’d said that I was really only in it for the qualification and wanted to go and do business, which I duly did,” says Farrar.

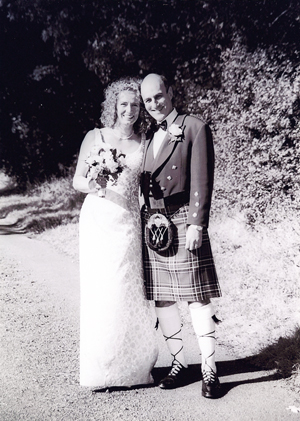

His business career took in Unipart Distribution Group, Barclays Bank and overseeing the demutualisation of Norwich Union, which led Farrar to move to South Norfolk where he met his now-wife Fran, and still lives.

However, as the company merged and changed, Farrar was left with a choice — move to London or York and leave his beloved coast behind, or find another job.

“So I did something I said I’d never do, which was join a government agency,”

he says.

“I’d seen myself then, possibly incorrectly, as a hard-nosed commercial animal — but I probably found out over time I wasn’t quite that.”

More by luck than planning, concedes Farrar, the organisation he joined as chief executive was the government research body, the Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science — which wrote the textbooks he studied during his oceanography degree.

From there he moved to the Construction Industry Training Board, which took him “firmly into the world of training and education” which he found was “something of a maze”.

But, he says: “I find it quite helpful to come into it reasonably cold because you look at things in a different way, and you’re aware it is complex and if I get lost in it sometimes how is a small business meant to finds its way around?”

The complexity of the system is what gives him pause over the apprenticeship reforms.

“Looking at the financial flows behind it, I buy into the principal of more employer involvement,” he says.

“But I remain wary. What works for a very large corporate with a very large training department is different to a small or micro business which needs help to get through each and every day — so I think the jury’s out.”

Meanwhile, the Trailblazers, he says, “have been a great catalyst” for refreshing the frameworks, but again, there’s a note of caution.

“The sector really does need stability to let the dust settle and really find out what and does not work,” he says.

What works for a very large corporate with a very large training department is different to a small or micro business

“With governments changing we end up going round the circle again — there’s always an understandable tendency from government to try to fit things into coherent boxes that look similar whereas each and every sector is very different.

“And the temptation is to tweak qualifications into something that isn’t want employers truly want.”

What attracted him to the AAT role, he says was “is making a difference”.

“For me that’s important,” he says.

“Ultimately we change people’s lives for the better and through that we change organisations for the better.”

But, he admits, this isn’t always how he’s seen FE.

“I think initially I always approached it from a business angle, the creation of value, economic value,” he said.

“I admit I came at this through business, it’s what I was trained to do but actually as I’ve gone on in general management, I’ve learned that life is about people.

“I think they’re complementary — if you’ve got the individuals and teams working and they are skilled you will get the economic value.

“Perhaps at the start of my career I was all about numbers and straight lines and very clinical ways of looking at things which is a very good discipline to carry with you over time, but actually I think I’ve become more rounded as a person as I’ve travelled.

“I hope not to become a crotchety old bloke, but every so often you can feel it coming,” he adds.

It’s a personal thing

What’s your favourite book?

I think one of the ones that left a mark was Goodbye to All That by Robert Graves. When I read it some while back, at the start of my career in the Navy, I think it struck a chord in terms of the territory, because it’s a well-written account of the terrible things that happened in the First World War trenches

What do you do to switch off from work?

Offshore sailing — I sail off the east coast, generally for pleasure but I do a bit of racing as well. I find it a completely different environment when you step into it. By definition you forget about the working week and any other stresses and strains that might go with it. It’s literally a breath of fresh air

What’s your pet hate?

I reckon life’s too short for pet hates, but if you pushed me, it’s people making a distinction between FE and higher education. I think it’s all part of education, training and skills development and our vocabulary as a nation needs straightening out a little. But that’s easier said than done

If you could invite anyone, living or dead, to a dinner party, who would it be?

Sir Ben Ainsley — I’d like to know what drives him and what motivates him, and how he thinks. My wife Fran would endorse the choice, so she’s invited too. And maybe Charles Dickens, too

What did you want to be when you were growing up?

When I was very young I recall wanting to be a Mountie [a Canadian mounted police officer] and then I focused on joining the Royal Navy, which I eventually did and thoroughly enjoyed it

Your thoughts