Disadvantaged apprentices are significantly more likely to drop out from their training, research has found, sparking calls for greater support for learners from poorer and ethnic minority backgrounds.

New findings from the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER) today also revealed apprentices who withdraw face lasting consequences and “wage penalties” compared to their peers who complete.

Researchers found that apprentice dropouts went on to earn significantly lower salaries and are more likely to be unemployed over the three subsequent years of withdrawal, suggesting they are not quitting to take up better paid work elsewhere.

The apprenticeship drop out rate, which hit a worrying 53.4 per cent in 2019-20 but improved to 38.1 per cent in 2023-24, has concerned ministers in recent years, prompting investigations.

NFER’s report, funded by the Gatsby Charitable Foundation, analysed the Department for Education’s longitudinal educational outcomes dataset from 2013-14 to 2020-21 and took learning aims and prior educational attainment data from the national pupil database to determine which characteristics are linked to withdrawals.

The study examined apprenticeship dropouts between 2014-15 and 2019-20.

Here are the key takeaways from the report:

Disadvantaged apprentices ‘most likely’ to struggle

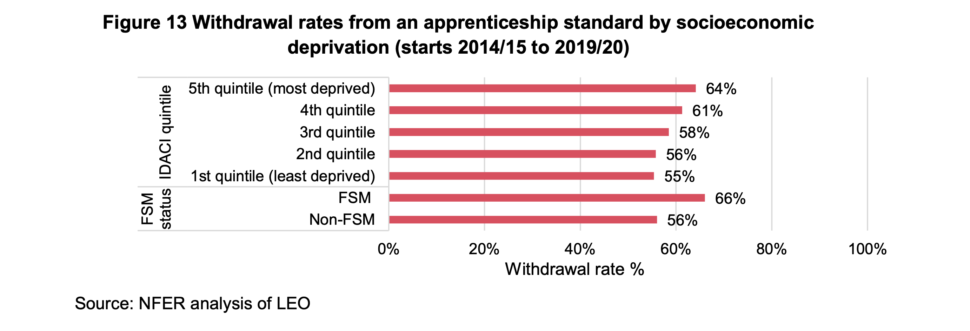

Learners who were registered as eligible for free school meals (FSM) at some point at school were 10 percentage points more likely to withdraw from their apprenticeship than their peers, the report found.

Researchers also examined apprentices living in the areas of highest deprivation as measured by the index of income deprivation affecting children and found they were nine percentage points more likely to drop out than those in the least deprived areas.

Jude Hillary, NFER’s co-head of policy and practice, said the findings show that government and the sector need to ensure disadvantaged apprentices receive “earlier, more targeted support – not just during training, but right from the point they start considering an apprenticeship pathway”.

Ethnic minority apprentices face additional barriers

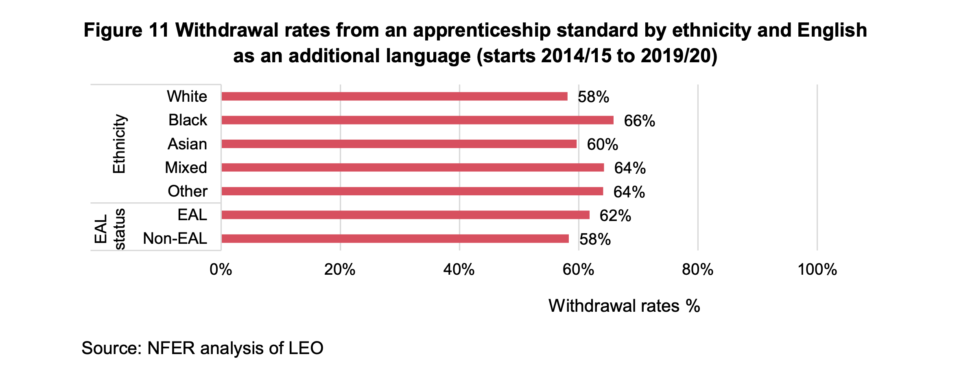

The report found learners from black and mixed ethnic backgrounds, and learners with English as a second language (EAL) face higher withdrawal rates.

Black apprentices had a withdrawal rate of 66 per cent between 2014-15 and 2019-20, mixed ethnicity learners had a 64 per cent drop out rate and white apprentices withdrew at a 58 per cent rate.

Once they accounted for variables such as GCSE attainment, qualification levels and socioeconomic deprivation, the NFER said the findings indicates that “ethnicity has a relationship with learners’ probability of withdrawal over and above the effect it has via other factors”.

Meanwhile, EAL apprentices had a 62 per cent drop out rate compared to 58 per cent for non-EAL speakers.

In terms of age, apprentices aged 16 to 17 and over the age of 25 were more likely to leave early (over 60 per cent) than those aged 18 to 20 (52 per cent).

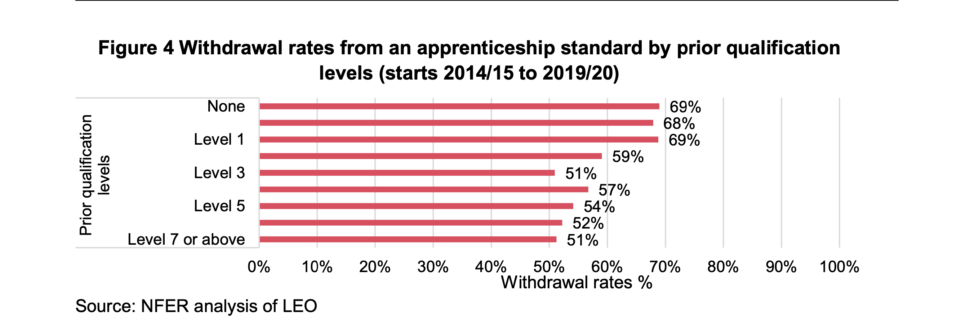

Low prior attainment contributes to dropouts

NFER also found that apprentices who already hold a level 3 qualification are eight percentage points less likely to withdraw from their programme compared to learners with no prior qualifications.

Similarly, the report said apprentices who have a grade C or 5+ in GCSE English and maths have been around four and six percentage points respectively less likely to withdraw than their peers without, after controlling for differences in other observed characteristics including overall GCSE scores.

“This suggests that learners’ maths and English prior attainment affect withdrawal over and above the effects of learners’ overall GCSE attainment,” NFER added.

No ‘great’ impact of functional skills requirements

From 2016, functional skills rules have required apprentices without ‘standard passes’ (grade 4 or C) in GCSE maths and English to continue studying these subjects.

Prior research, including a recent 2024 report based on interviews with 71 employers, has claimed that functional skills requirements have been a key barrier to apprentice completion.

NFER said its analysis suggested that the effects of learners’ GCSE maths and English results on their probability of withdrawal “did not change greatly between those that started in 2014-15 and 2018-19”.

These results “appear to suggest that the relationship between learners’ maths and English GCSE results and withdrawal may not have changed greatly after the introduction of functional skills requirements”.

However, researchers acknowledged it could be that the effects of functional requirements on withdrawal were “lagged, and/or functional skills requirements may have influenced employers’ choices about who to accept onto apprenticeships in the first place”.

Last year, DfE scrapped the functional skills rule for adult apprentices, but kept the requirement for 16 to 18-year-old apprentices.

EPA introduction did not impact withdrawal timings

The introduction of the end point assessment (EPA) in 2017 through standards, which replaced frameworks, did not appear to affect the timing of apprenticeship withdrawals, NFER said.

Researchers had expected to see an increase in dropouts towards the end of the apprenticeship standard from learners concerned about taking the EPA.

However, apprentices got a similar proportion of the way through their apprenticeship (47 per cent for standards compared to 43 per cent for frameworks on average) before quitting, the analysis found.

This finding does not, however, “preclude EPA contributing to the higher average withdrawal rate observed for apprenticeship standards compared to frameworks”.

NFER noted that qualitative research insights have suggested that EPA “may be leading some apprentices to withdraw”.

Size and quality matters

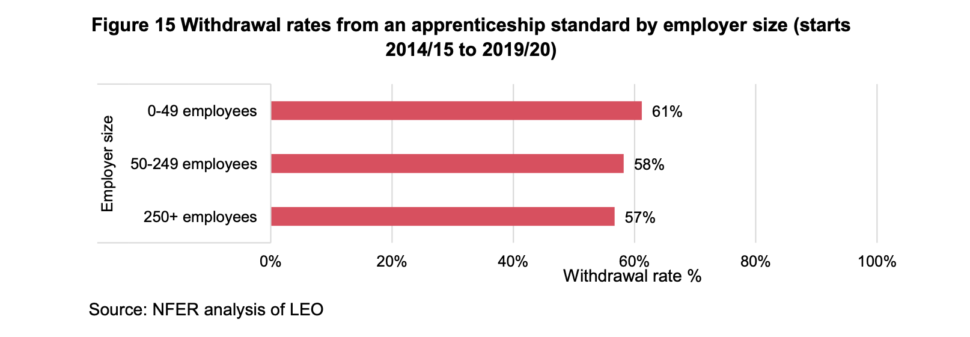

The report found apprentices employed by smaller organisations or employers new to apprenticeships are more likely to withdraw than those working for larger, more experienced employers.

Learners working for organisations with 250+ employees are four percentage points less likely to withdraw than learners at organisations that employ less than 50 people.

The report also revealed more experienced training providers (with three or more years in the sector) are associated with lower withdrawal rates, according to regression analysis which factored in differences in apprenticeship, individual, provider and employer characteristics.

“This highlights the benefits of supporting existing providers to scale and avoiding experienced providers exiting the apprenticeship market, particularly in occupational sectors associated with higher withdrawal rates,” researchers said.

Meanwhile, apprentices trained by Ofsted-rated ‘outstanding’ providers are 16 percentage points less likely to withdraw compared to learners trained by providers with an ‘inadequate’ rating (54 percent compared to 70 percent), the research found.

However, the difference in withdrawal rates between ‘outstanding’ and ‘requires improvement’ providers was a more modest five percentage points.

Apprentices not quitting for better paid work

The study examined apprentices’ earnings before, during and after their apprenticeship, drawing upon data from HMRC, their employers from the inter-departmental business register (IDBR), and their apprenticeship providers.

The report found apprentices that are paid more in the first year of their apprenticeship are less likely to withdraw, but effect sizes are small.

NFER calculated that for every 10 per cent increase in earnings in the first year of learners’ apprenticeship, their probability of dropping out decreased by around half a percentage point.

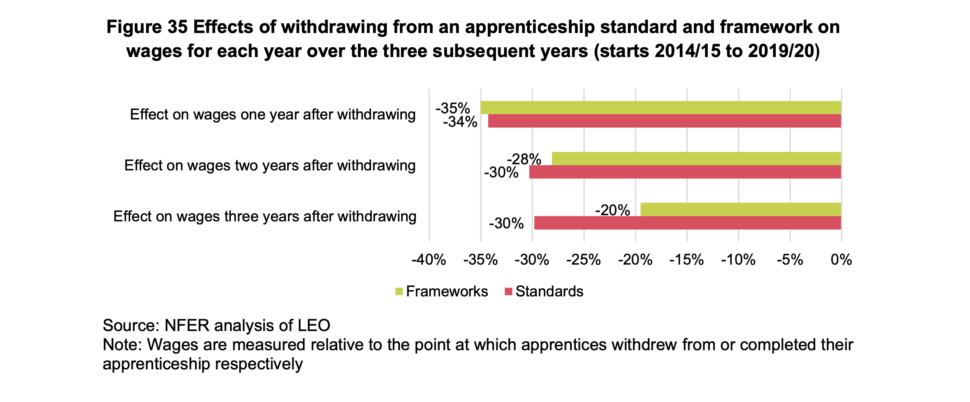

However, the study showed learners who did not complete appear to suffer significantly lower wages and are more likely to be unemployed in the three years after dropping out compared with their peers who finished.

“This suggests that apprentices who withdraw are not quitting to take up better paid work outside of the apprenticeship system in the medium-term (as we are comparing outcomes once both groups finish their apprenticeship),” it said.

Additionally, the wage gap was much wider when apprentices dropped out under standards than it was for apprenticeship frameworks.

Researchers did add that wage differentials may “partially” reflect dropouts having less experience than completers.

Apprenticeships ‘clearly harder’ to get onto and complete

NFER called for targeted additional support towards apprentices, employers and providers that have a higher chance of dropping out.

It also recommended assurance that there are adequate pre-apprenticeship programmes that prepare learners to fully complete the qualification, particularly targeted towards those with low prior attainment.

NFER suggested that further support could be towards apprentices on level 2 programmes and ethnic minority learners, but did not specify how officials should improve support.

Ministers in the past have sought to better understand why apprentices drop out such as introducing an exit feedback tool and more recently, foundation apprenticeships.

“Apprenticeships are clearly now harder for young people to get onto and complete, particularly for learners with lower prior attainment and low or no prior qualifications. New foundation apprenticeships may be one way of effectively responding to this challenge,” the report said.

A Department for Work and Pensions spokesperson said: “This government is committed to ensuring people of all backgrounds can access, and benefit from apprenticeships.

“Our recent £725 million investment will simplify and modernise the apprenticeship system, making it more efficient and responsive to the needs of employers and learners.

“We are creating an apprenticeships system that addresses the nation’s skills challenges head on and are simplifying it to give businesses the flexibility to develop the skills they need.”

The term ‘drop out’ is unhelpful.

An apprenticeship can be unsuccessful because of the employer, training provider, economics conditions, policy impacts or, more commonly, complex combinations of reasons. The phrase ‘drop-out’ infers that it’s the apprentice to blame and has negative connotations.

The Gatsby / NFER report doesn’t use the phrase.