The Department for Education overspent its apprenticeships budget for the first time last year in what has been described as a “landmark moment”.

Experts now fear further apprenticeship spending restrictions may follow the scrapping of public subsidy for level 7 programmes and warned there is “limited” headroom for funding non-apprenticeship courses through the reformed growth and skills levy.

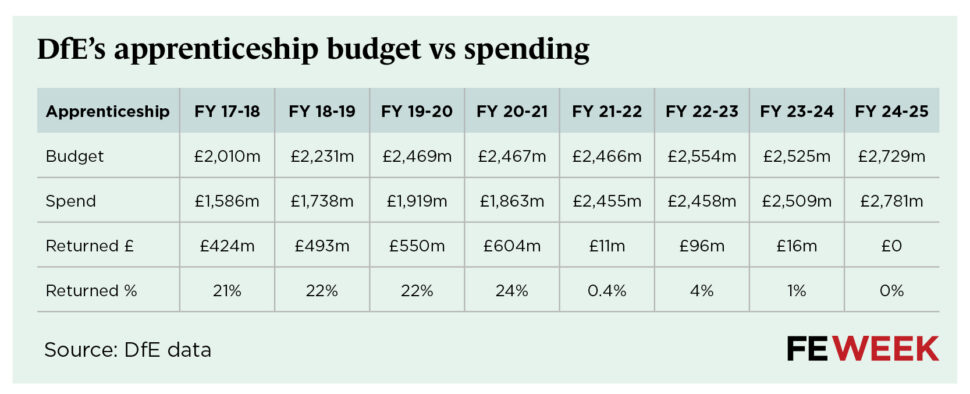

England’s apprenticeships budget in 2024-25 was originally set at £2.658 billion before rising to £2.729 billion partway through the financial year.

DfE’s recently published annual accounts show apprenticeship spending hit £2.781 billion, meaning a £123 million (4.6 per cent) overspend on the original budget and a £52 million (2 per cent) overspend on the revised budget.

To cover the excess, the DfE authorised £52 million in “virements” – a transfer of funding from another budget line to the apprenticeships budget.

The DfE told FE Week the higher level of spending was caused by more starts and achievements compared to previous years, as well as increases to some funding bands.

Simon Ashworth, deputy CEO at the Association of Employment and Learning Providers (AELP), said: “This marks a landmark moment after years of unspent funds being returned to the Treasury.

“It reflects the aggregated impact of apprentices already on programme and the financial consequences of increased achievement rates.”

‘Government will face further trade-offs’

Despite spending more on apprenticeships than had been budgeted, the DfE claimed there wasn’t technically an overspend because officials were able to match the full spend through virements.

Stephen Evans, chief executive of Learning and Work Institute, said: “Small variances to budgets do happen, and in this case a 2 per cent overspend seems to have been offset by underspends elsewhere.”

The DfE refused to say what other budget line was raided to cover the apprenticeship overspend.

FE Week has been reporting on potential apprenticeship overspends since 2018 following an initial warning from the Institute for Apprenticeships and Technical Education.

The issue stems from soaring numbers of higher-level apprenticeships that are more expensive to deliver than lower-level programmes.

A National Audit Office report in 2019 said there was a “clear risk” that apprenticeships were not financially sustainable for the government, as the costs were around double what was expected in 2015.

Pressure was eased when the Covid-19 pandemic hit and numbers of new starters fell. But in 2021-22 DfE’s apprenticeship budget was underspent by just £11 million, or 0.4 per cent.

The underspend in 2022-23 was £96 million (4 per cent) and in 2023-24 it was £16 million (1 per cent).

Almost £2.2 billion of the DfE’s apprenticeship budget has been returned to the Treasury since the levy launched in 2017-18 to 2023-24. No apprenticeship funding was returned to the Treasury in 2024-25.

Treasury boosted the DfE’s apprenticeships budget by 13 per cent to £3.075 billion in 2025-26 owing to the mounting pressure.

‘Future overspends may not be so easily absorbed’

Evans said: “The apprenticeship budget has been basically fully spent for a few years now. Even with the rise to £3 billion this year, there is likely to be limited room for flexibility in the levy outside apprenticeships.

“And prioritising apprenticeships for some groups, like young people, is likely to require reductions for other groups, as we’ve seen recently at level 7. Either the budget needs to rise further, or the government will face further trade-offs in the future.”

There is likely to be a surge in level 7 apprenticeship starts this year before levy funding is switched off in January 2026, and foundation apprenticeships are being rolled out this autumn. Another budget strain could be the potential launch of the new level 2 business administration standard, which is likely to prove highly popular.

The DfE is aiming for 30,000 foundation apprenticeship starts in their first year. Kate Ridley-Pepper, the DfE’s apprenticeships director, recently warned of further potential “savings” and “trade-offs” if the new scheme became too popular.

She told last month’s AELP conference that the level of spending on apprenticeships “is not sustainable in the long run”.

The government also still plans to turn the apprenticeship levy into a growth and skills levy that funds non-apprenticeship training, which will include new short courses from April 2026.

Ashworth said: “We welcome the additional £350 million injected into the 2025-26 budget, which has provided much-needed headroom and helps reduce the impact of Treasury top-slicing in the short-term.

“However, the recent defunding of level 7 apprenticeships won’t deliver quick savings, and in a tight fiscal climate, future overspends may not be so easily absorbed. Greater clarity on apprenticeship funding beyond 2025-26 will be increasingly important for long-term planning and stability.”

Treasury margin shrinks

Mark Corney, senior policy adviser at the Campaign for Learning, said that despite higher levels of apprenticeship spending the Treasury margin is shrinking.

The money raised through employer levy contributions isn’t hypothecated in the sense that it doesn’t determine the apprenticeship budget – this is separately set by the Treasury.

The top-slice is the amount the Treasury keeps after collecting the funds paid by employers and dishing out spending for apprenticeships to the DfE and devolved nations.

This margin was around £800 million in 2024-25.

Corney pointed out that the Office for Budgetary Responsibility (OBR) has estimated that total apprenticeship levy paid by businesses in 2025-26 will be £4.2 billion, which is £100 million more than the outturn of £4.1 billion in 2024-25.

The levy raised £91 million more in April to June 2025 than it did in the same period last year.

Corney said Treasury is on track to raise £4.2 billion or more in 2025-26. When the DfE’s £3.075 billion budget is distributed and around £500 million is dished out to the devolved nations, this would leave a top slice of around £623 million.

The levy was sold to businesses as a hypothecated tax (i.e. to be spent on what it was raised for).

It’s like purchasing full fat milk, but finding semi skimmed in the bottle.

Imagine a world where all levy receipts had been in the budget since 2017 and used to incentivise apprenticeship opportunities, adequately fund standards and drive quality improvement. More jobs, more economic activity, higher tax receipts, fewer NEETs, fewer skills shortages, lower welfare bill. Ultimately, would the sum of the benefits outweigh the amount the Treasury has retained? (if you think not, would you propose that the Treasury retains the entire Levy take and have no apprenticeships..?)

I just find it laughable that a member of the Department told us what they believed “off the job” was and who should provide this training and this was in complete contradiction to what the training provider told us it was.

Nobody knows what the real answer is for something that has specific legislation to follow. If there was more of a holistic approach to apprenticeships, surely they wouldn’t cost so much on the first place, Instead it is all tied up in beaurocracy and red tape!

The apprenticeship model does not suit every individual and therefore should not be offered to everyone, the skills & behaviours are aimed at younger people who need guidance in the first approach to the work place, Not 40 year old plus individuals who ultimately would like a professional qualification.

So, no money handed back in 2024/25. Very interesting as we are still in that year. R12 figures not released yet and wont be tied up until R14 is released in Jan 2026.

Our levy paying business has already handed back 250k in 24/25.

Where has this money gone??? What are the Government actually doing with current Levy money, how are they overspending when every levy paying business i talk to hands at least 20% of the levy pot back every year.

There needs to be full disclosure of what is paid in and where it goes, other than paying out ministers and quangos wages!!!!!!

Unpicking this: This is the financial year, not the academic year. Levy payer funds are not “handed back” – they trickle through and then fund the “government’s contribution” to pay the training costs for non-levy payers. It’s only after that point that funds are returned to the central government.

An opaque system that is still understood by so many employers.

The apprenticeships budget is a distraction.

Bottom line is that the spend on apprenticeships is less than the income from the levy.

Like every other voucher system it has design elements which guarantee there will be surplus (more income than possible expenditure). The rolling 24 month expiration of funds for example, or not having specific provision available in every locality, guarantees a surplus.

FE Week should add in another line to the table – levy income each year. Allowing folks to ignore the budget and see the gap between income and expenditure clearly.

Levy budget = stealth tax, use it or we will just return it to the treasury.