Darren Hankey is keen for his students to grasp the tantalising opportunities to acquire net zero skills that are emerging in his region as a way of pulling themselves out of poverty.

In the college’s 175-year history, Hartlepool has gone from being an industrial powerhouse to one of England’s most deprived towns. Students’ behavioural problems are presenting an ever-greater challenge.

They are bearing the brunt of the cost-of-living crisis, Hankey tells me, with bursary applications going “through the roof”. But the country’s efforts to wean itself off fossil fuels are creating apprenticeship opportunities which offer a way out of entrenched cycles of social deprivation.

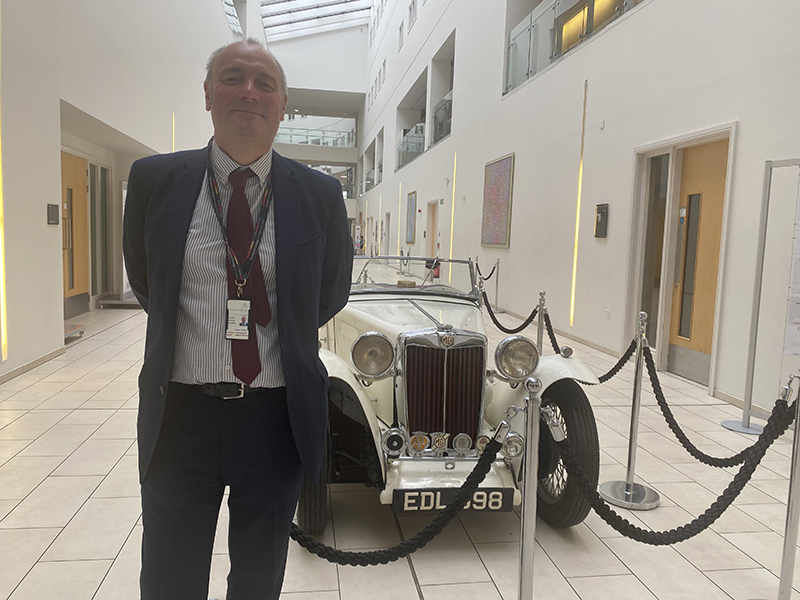

Hankey, who has just marked ten years as principal at the college, spent the morning before my visit hobnobbing with business executives from SeAH Wind, who were also visiting the college. The Korean company has invested £450 million in a monopile manufacturing facility in nearby Middlesbrough – the first of its kind in the UK.

The monopiles are needed to build one the world’s biggest offshore wind plants, on former industrial land at Teesworks, part of regional mayor Ben Houchen’s grand vision for the Tees Valley region to lead on the net zero agenda. The Tees Valley local skills improvement plan (LSIP) includes hydrogen and carbon capture and storage projects as well as offshore wind, creating around 10,000 jobs over the next five years.

Over 2,000 of those jobs are expected to be created through the monopile factory and its supply chain, with SeAH taking on 14 Hartlepool College apprentices in its first cohort.

Hankey shows me new facilities where students are learning to maintain electric vehicles and explains how many of the college’s 1,000 apprentices (who make up a fifth of its total student population) are in an engineering discipline, with many joining companies in the supply chains of Nissan and Hitachi.

This year the college’s apprenticeships division was rated ‘outstanding’ by Ofsted. Hankey attributes this to the significant work they put into finding out what employers want.

‘I’m not one to be sat in my office looking at spreadsheets’

For Hankey, developing the character of apprentices is “just as, if not more important, than the qualifications themselves”.

We walk past a new student who isn’t wearing his college badge, and Hankey tells him to make sure he brings it tomorrow. “You’ve got high standards, I recognise that about you – they just dipped a little bit today,” he gently warns him.

Interacting with students – whether that’s as a teacher or wandering in and out of classrooms (something that he encourages his senior leadership team to do regularly) is the part of his job that Hankey enjoys most.

“I’m not one to be sat in my office, looking at spreadsheets.”

He is, though, one of the country’s most visible college principals on social media, airing his views on policy and posting reminders of pro-FE statements made by former cabinet ministers like Gavin Williamson and Boris Johnson to expose how funding has not followed sentiment.

Working poor

In the century or so after the college opened in 1849, many of its students went on to jobs in the local iron, steel, shipbuilding and marine engineering industries. But much of that is now gone.

Under Thatcher, thousands of steel workers lost their jobs, just a couple of decades after the last ship to be built there set sail.

Industrial decline left its residents feeling neglected. During Brexit, Hartlepool recorded the biggest margin of victory in the region for the Leave campaign – 69.6 per cent of the vote.

Ironically, Hartlepool College’s website still features the EU flag branding for the European Social Fund next to the college’s own logo, despite the fact that this funding has now ceased – a reminder of how EU money was central to boosting skills in the region.

These days, the college hallways are adorned with posters featuring inspiring quotes and pictures of icons such as Bukayo Saka and Marcus Rashford, because Hankey sees positive role models as a way of countering the growing influence of popular figures like Andrew Tate. Last year, six of his students were targeted for criminal and sexual exploitation.

The principal himself is also a source of inspiration for the many college students having to retake their English and maths GCSEs. Enrolment for those courses has almost doubled this year, from 642 to 1,204.

Hankey knows first-hand just how “disheartening” that sense of failure can be. He passed his maths GCSE at the age of 22, after attending night school at Leicester College.

“I tell them, get that GCSE before I got it,” he said.

Education was not seen as a priority for Hankey growing up in Leicester. After his parents separated when he was a young boy, his mum worked hard to put food on the table, which often meant going from a day job cleaning offices to working evenings in a pub.

He sees his own background in many of Hartlepool’s current students; they have parents who work hard but still cannot make ends meet. Last year, around half of the college’s bursary applications came from working families, something they had “never really seen before … it was eye-opening.”

Second chance education

Hankey left school at 16 with the equivalent of three GCSEs and got a warehousing job at WH Smith, sweeping the floor and picking up litter. The initial excitement of earning a wage quickly wore off, and the work became “quite monotonous”.

Fortunately, WH Smith sent him to night school at Leicester College when he was 18, where he took a management course and then went on to Sociology and French A-levels.

“If you’d told me when I first walked through those college doors that I’d still be there four years later, I wouldn’t have believed you. But I really thrived in that environment.”

WH Smith paid for all Hankey’s courses, apart from French, which only cost him £50.

It was a Leicester College lecturer who approached him after an evening class to suggest he went next to university. Hankey drove home with “fireworks going off in [his] head”.

“He thought I’d have an aptitude for it. No one had ever said anything like that to me before. I knew about Oxford and Cambridge, I knew Leicester had a university and a polytechnic, but I didn’t know the difference between them. I just had no clue.”

Beverly Hills 90210

Hankey had some “wanderlust” and applied for a business and economics degree at Sunderland University which included a year in Austin, Texas. There, he was placed in “the equivalent of Beverly Hills 90210”, sharing a dorm with a student who had been handed a $30,000 Ford Mustang as a high school graduation gift.

“When I left school, I went down the working men’s club with my grandad and got a pint of bitter!”

Hankey found part-time work as a learning support assistant in maths and statistics classes, which gave him the “bug for teaching”. He spent the next six years teaching at FE colleges in inner-city London, starting with entry-level courses and moving on to teaching marketing and HR.

When the opportunity arose to move back up North as Hartlepool’s assistant principal in 2001, he grabbed it. By 2013, he had climbed the career ladder to principal and chief executive.

Bursary blues

The percentage of Hartlepool’s 16-19 cohort applying for bursaries usually “fluctuates between 40 and 50 per cent”, but last year it was 95 per cent and this year it is gearing up to be even higher. This time last year, the college had received 750 bursary applications. They have already had 850.

Hankey believes poverty is forcing increasing numbers of young people to leave college to take on paid work.

Last year the college’s achievement rate was around 80-85 per cent, whereas normally it is in the nineties.

A big bugbear for Hankey is the legwork that goes into students having to apply for free school meals. For schools, the process is automatic.

“We’ve got a great team who do that, but I’d rather they’re doing something different than processing all that paperwork.”

The bureaucracy means around 100 of those entitled to free school meals go unclaimed because those young people live in “a chaotic family with parents or carers dependent on alcohol or drugs. They can’t get the evidence to us, through no fault of their own.”

The college uses bursary funding for those students, because “we know there’s a need”.

“We just try to spread the jam and make it work.”

‘It’s absolutely tough’

The college tops up the standard free school meal allowance from £2.53 per student – which “you’d struggle to feed a growing teenager on” – to £3.50. Some students receive double, “because otherwise they’re probably not going to be eating. It’s absolutely tough.”

Ronnie Bage, the college’s welfare manager and resident knight in shining armour, welcomes me into his office. It is crammed full of donations he has been collecting – bikes, car seats, clothes and toys – to give out to needy students.

When his mother-in-law died six months ago, he brought the “full house” in and “gave it to all the refugees”.

“I know cooking is important in their culture, so I brought slow ovens.”

He always carries spare change in his pocket to hand out to needy students, although Henkey emphasises that “we’ve told him not to”.

“I know, I’m sorry, boss,” Bage responds.

He points to a new student walking past who lives with her nana, along with five siblings.

“None of them have been to school and they don’t have any standards. I fed them all last week – they were lovely then. But now they’re kicking off. It’s trauma that’s causing it.”

The college works with local civil engineering firm Seymour on training up out-of-work adults (including many former prisoners) in groundworks skills, and Bage receives a phone call about a young man who had found himself homeless following a domestic incident. He is hungry and crying, and Bage announces that he will “go over there and give him all the information he needs” to find accommodation.

Another engineering course the college offers helps unemployed students to get jobs in the rail sector within just six weeks.

The students are naturally required to be clean of drugs and alcohol, which Hankey says means the first day on that course is “always quite entertaining” as “people turn up with Ribena bottles. We know what they’re trying to do”.

Bage believes that student behaviour has got worse as council support has fallen away.

“We’re not social workers, but the skills our team has are second to none. We’ve had to upskill ourselves, just to deal with the young people that come through those doors.”

But he is incredibly proud to work for the college, which is “amazing in its facilities and staff”. “We don’t want pity. However, how do we keep pulling people out the river? How do we cope?”

Your thoughts