Graham Hasting-Evans’s career has revolved around building. “I wanted to do something practical, to build things,” he says.

“And then from building things, I started to build organisations and build people’s skills.”

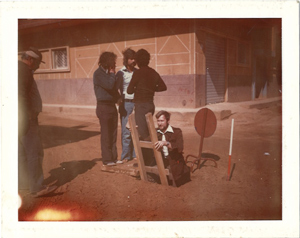

It’s a career that has taken him from a small Welsh farm, to Libya, Thailand, the London 2012 Olympics and to his current role as chief executive of awarding organisation NOCN.

We liked living in Libya. It might sound strange, but we did

The turning point, from building things to building up people, he says, was while he was working at Bristol City Council.

“I will always remember this one chap was brought in to be sacked because he and his whole team — there were four of them — were useless,” says Hasting-Evans.

“So they came in and I sat them down and it turned out that of the four of them, three couldn’t read or write — including the supervisor — and they had never been trained.

“So I got the three that couldn’t read or write into literacy studies at the local college and there was a bit of reluctance, but they did go.

“And about three months down the line, they were one of the better workforce groups, and they were quite productive.

“It taught me that if you can invest in people in the right way, you are giving them something worthwhile, and the employer is getting something worthwhile rather than sacking them and starting again.

“It just taught me the power of training — don’t give up on people, give them a chance and that was it, I just got more and more into it.”

Hasting-Evans, now aged 62, had always wanted to be an engineer and he learned his desire to move forward and meet deadlines from his parents, farmers Nora and John.

If you can invest in people in the right way you are giving them something worthwhile

“My family were farmers and soldiers, and builders, so growing up there was always a sense of ‘that’s got to be done, it’s that time of year, this must be done’,” says the dad-of-two.

“And when I went to university in Cardiff, my engineering courses was like that — things have got to be done, make a decision now and get on with it, so I just got used to that way of thinking.”

Hasting-Evans jumped at the chance to do a degree with a year in the industry, spending six months at an engineering company in Cardiff and six months in Denmark, building a new town which, he says, “was fantastic — that experience was really enriching and opened your mind up”.

It was at university that Hasting-Evans met his future wife, Maggie.

He graduated and was offered a job at the company he had worked for during his course and the following year he and Maggie bought a house and got married.

However, the company had other plans.

“We hadn’t actually lived in the house at this stage, we’d gone on honeymoon, came back on the Monday morning to be told ‘You’re going to Halifax for a year — sell your house, off you go’,” he says.

“So we went to Halifax, then we went to Preston, then we went to Libya.

“I suppose I worked in an industry where people moved around, and moving around the world, I felt, was a great experience.

“Not everyone does — a lot of people were frightened of it… but I love those sorts of things.”

The couple moved to Libya in 1976, during the war between Libya and Egypt.

“That wasn’t necessarily the most pleasant of experiences, but we were safe,” he says.

“We were in Benghazi, probably not that far from the front, but it only lasted about two weeks and petered out.”

He adds: “It was obviously very tense, and there were rumours, people saying ‘they’re going to bomb Benghazi tonight’ and of course it didn’t happen.

“The Libyan people were fabulous, a really welcoming, nice people.

“We liked living in Libya. It might sound strange, but we did.”

Their first son, Edward, was born in Libya, and second son, Geraint, was born in Malta, where Hasting-Evans was sent to work after he had completed his project in Libya.

The family also lived in Thailand, where once again, Hasting-Evans had a brush with political turmoil.

“I was working in Thailand and I had to visit somewhere and the only way to get to it was cutting through Malaysia and back into Thailand — it was the only road through.

“And there were bandits and a war on the border, so I had to have a Thai army platoon take me half way across no-man’s land, then a Malaysian army platoon take me around to the other side, then picked up the other side by another Thai platoon, with about 10 soldiers in an armoured vehicle, then all the way back, so I could spend about three or four hours there doing some work.

“I wondered afterwards, ‘Why am I doing this?’ It was a bit surreal at the time.”

As Edward, now in his 30s, got to eight years old, the family returned to England, and Hasting-Evans began to move towards “building organisations, and building people”.

In 2006, Hasting-Evans was brought onto the Olympic project as head of strategy, and in 2007 moved over to develop the employment and skills strategy for the London 2012 Olympics.

He laughs when I compare him to Hugh Bonneville’s character in the BBC sitcom 2012 about a fictional Olympics delivery team.

“It’s a bit like Yes, Minister, and like anything else there are strains of truth in it but it’s the exaggeration which makes it fascinating TV, and makes everyone laugh and enjoy it,” he says.

“But what struck all of us that worked on it — a really tough, professional team — was the feeling that this is going to get done, we are going to make whatever decisions we need to, whenever we need to make them.”

The £9bn contract involved employing around 100,000 people over the five year run-up to the games and the games themselves.

“We had joined up all the dots, so from Jobcentre Plus to being sifted out to whether you could go through the training, if you pass the training then on to a job,” he says.

“Some had been unemployed and written off, some with three generations of unemployment — but we got them into work, we gave people mentors.

“On that scale, you can do something, you can create a programme over a period, and actually use it to help skills development within the industry — and I enjoyed doing that, it was really fulfilling.”

He adds: “I remember getting told a few years ago, when I was told I was moving to Bristol not to think of it as a challenge — it’s an opportunity.”

Now at NOCN, Hasting-Evans can see plenty of opportunities for the organisation in the sector and finally has no plans to move on.

“I’ve enjoyed my time at NOCN — we’ve got a great board and great teams, so I am enjoying doing that very much indeed,” he says.

———————————————————————————————–

It’s a personal thing

What’s your favourite book?

I recently enjoyed The White Queen. It was historical, which I like, but it was all political intrigue and family and fighting. Before that probably Catch 22, which had the same mixture of intrigue

What do you do to switch off from work?

I walk a lot. I live in the Peak District National Park so I go walking in the national park, rambling and scrambling up hillsides and things like that. It helps me to switch off. I’ve also got two Cavalier King Charles spaniels dogs, Betty and Alice

If you could invite anyone to a dinner party, living or dead, who would it be?

Alexander the Great and Barack Obama

What did you want to be when you grew up?

An engineer

What’s your pet hate?

Taking too long to do things. I like to do things quickly, which probably comes from my time in construction. I know people say builders take forever, but in major civil engineering contracting, things have to be done

Your thoughts