Last month, education giant City & Guilds raised a few eyebrows by calling for the creation of a new independent body to oversee skills policy in the UK.

Not convinced that a new quango is what the sector needs, FE Week editor Nick Linford sat down with the organisation’s chief executive to see if he could persuade him otherwise. Here’s how it went.

City & Guilds has a long history, not just in terms of being the most recognisable name in the vocational education space for 140 years.

They have also for many years invested in commissioning research and advising governments around the world, rarely holding back from presenting potentially unflattering views.

This has continued under their current chief executive, Chris Jones, who since 2008 been at the helm of the group that last year turned over £144 million, employing nearly 1,400 people.

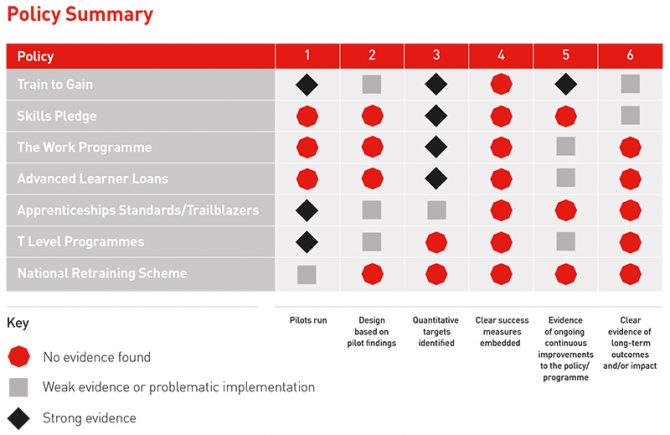

Jones has not shied away from a bit of Department for Education bashing, being regularly critical on social media on whether T-level reform represents value for money to date and most recently “highlighting the urgent need for more considered policy development that is based on substance, not style”.

And with reference to the recent level 3 and below qualification consultation, he accused the DfE of “sadly” having “no track record” when it comes to having “clear outcome

measures established at the outset”.

One solution to the FE policy failures, Jones told me in a broad-ranging interview, was to establish another quango, to be called the Skills Policy Institute.

Reviews are applauded, debated, then shelved and forgotten about

This is not the first time Jones has proposed a new organisation to “hold the government to account by scrutinising skills”.

The recommendation featured in the first City & Guilds Sense & Instability report in 2014, and again in the 2016 update.

However, the “body with independent oversight” was not given a name and was at that point compared to the Office for Budget Responsibility.

So now, in the third Sense & Instability report we have the proposed name, Skills Policy Institute, and this time the Education Endowment Foundation is used as a comparison – a research organisation established with £120 million of public money.

There had been some disquiet on social media about the idea of another quango – to add to the myriad organisations with oversight of just apprenticeships that featured in the National Audit Office’s most recent report into the sector.

Jones has been critical of constant policy change, so he wants to be clear that his idea of a new “quango is not necessarily being designed or considered as a way of saying to driving more change in policy.

“So it’s not saying, ‘Let’s create something that is independent, and more policy for the sake of policy’. It about getting the policy right and making sure the policy that is put in place gets delivered well.”

A new Skills Policy Institute would build institutional memories – what has worked and what has not

My challenge back to Jones was to ask him: why create another quango with all the associated bureaucracy when the government can instead commission research or high-profile independent reviews, such as Wolf in 2011, Richard in 2012, Sainsbury in 2016 and most recently Augar, as task-and-finish groups?

But Jones dismisses reviews “that can be applauded at the time they are published, much debated, but then potentially be put on the shelf and forgotten about.

“And I think that, for me, is one of the risks that what we have here is something that typically sees lots of research reports being commissioned with lots of recommendations, but do they all make sense over time? Do they connect with each other? I would argue perhaps not.”

Instead, he insists a Skills Policy Institute would build “institutional memories, the basis of what has worked and what has not”.

He goes on to say that it could be “quite small. About 10 to 15 people. So it’s not substantial. It doesn’t have to be. This is not about creating bureaucracy for the sake of it. It’s about creating something that has substance in what it says and does.”

Intriguingly, before I ask where the money would come from to pay for this new quango, Jones offers up the apprenticeship levy.

“We are talking about something that could be funded with a relatively small proportion of the levy and arguably could be a very good use of a very small proportion of the levy,” he says.

What then follows is a rather critical view of the Institute for Apprenticeships and Technical Education (IfATE), a quango that is in fact funded from levy receipts and has quickly now grown to around 150 staff.

“I don’t see anything yet that is coming out of the IfATE that has been research-led. Looking closely at the specific outcome measures it needs to be putting in place, it’s filling a slightly different purpose at this moment in time.”

This strikes me as the first time I’ve heard Jones or City & Guilds criticise the relatively new IfATE, and when I point out that they have researchers, he is quick to express a “hope” that they would consider value for money.

“If the IfATE is there to help administer apprenticeship policy, it is essentially a ministry of apprenticeship policy,” he says.

I think they [the IfATE] should be doing more

When asked whether the IfATE was meant to be independent, Jones says: “That was the idea. Do we see that coming through? I don’t see enough evidence of that, personally, coming through of this being something that has genuine independence. I haven’t seen them publish a report about the future of the workplace in 2030 and how the apprenticeship strategy must evolve to support that. Funding has to move from A to B, we need to have these standards… I haven’t seen that.”

Jones claims he hasn’t given up on the leadership at the IfATE, “I just don’t see what they are doing today as fulfilling the role of what we see in terms of the Skills Policy Institute. They (the IfATE) are administrating policy. If they believe they should be doing more, that’s for them to determine what they should do. I think they should be doing more,” he adds.

During the course of the interview Jones compared his proposed Skills Policy Institute to the small National Infrastructure Commission and even the UK Commission for Employment and Skills, shut down in 2017 but described by Jones as “forward thinking, beginning to look where some of the potential interventions might need to be over time, thinking where and how employers can begin to shape the policy to a greater extent than they perhaps are at this moment in time”.

My experience was that the UKCES had few fans before being shut, few mourned its passing and it is now rare for it to be mentioned on the FE policy circuit.

So Jones has failed to persuade me that a new quango is part of the solution for avoiding poor policymaking or to stop good policies failing.

No matter how independent a Skills Policy Institute would claim to be, its income and thus survival, along with the actual decision making, would be in the hands of the democratically elected officials.

And frankly, the skills sector is not short of quangos, policy influencers and talking shops, at both a national and regional level.

Put bluntly, moving deckchairs around or adding new ones will not stop the sinking feeling.

What we are really short of is sufficient investment in the delivery of further education and skills.

Your thoughts