After 62 years, the Leeds College of Building has just appointed its first ever female principal. Jess Staufenberg asks the incoming Nikki Davis what she’ll do to grow the vanishingly small proportion of female learners studying construction

Nikki Davis, currently vice principal at Leeds College of Building, is set to become its first ever female principal in August this year: a small watershed moment in the history of a college set up in 1960.

She will be joining the ranks of the 48 per cent of principals in FE who are women, swelling their number just a tiny bit. In many respects, that percentage is pretty impressive, and one the further education sector has every right to be relatively proud of – after all, that’s almost half.

That proportion is also ahead of other education sectors: according to the latest Association of Colleges figures, only 40 per cent of secondary school headteachers are women, and only 31 per cent of university vice-chancellors. Perhaps the traditional, academic sectors still revere the male brain more than the less traditional, vocational sector, whose whole raison d’être is to champion the underdog.

But the FE staff workforce is 61 per cent female, according to the Education and Training Foundation’s latest data from 2018/19. So men still disproportionally rise to the top role – and, partly as a result, the gender pay gap in the sector persists too.

Davis is clear: time and again in FE she has been encouraged by the professional women around her to be ambitious for herself, with three women acting as key role models. Now, it is Davis’s turn to act as a role model, not only for aspiring female leaders, but, just as importantly, for her students.

Her college is dedicated to courses in construction (and the only one of its kind in the country), but it has a vanishingly small female learner population: only eight per cent. It will be the biggest challenge of her impending leadership.

Before Davis tells me about the three women who mentored her, she recalls her own mum, a Yorkshire woman who brought up her, her brother and sister, first in Hampshire (Davis says she started off life “with a strong southern accent”) and then in Cheshire. Her father worked with IBM, the technology corporation, and her mum kept the home.

“She had that strength of character: she was definitely the one in charge when I was growing up,” smiles Davis.

Another key influence alongside her mum was sport, with Davis admitting to being secretly “competitive, but only about the things that matter”, doing everything from netball, tennis and athletics to county-level hockey. It was another arena in which she could build her confidence as a young woman.

But it was perhaps a move by her dad which deeply impacted on Davis’s self-belief and skillsets. It was New Year’s Eve, and the restaurant her older sister worked at rang to say they were short-staffed.

“My dad said, ‘Go and work with your sister,’ and packed me off. I had literally just turned 13!” she laughs. “I don’t know if that was allowed, and I don’t think I was meant to still be working at midnight, but I actually loved it.”

The story might shock some educators, but the sense of autonomy and challenge the experience gave Davis is arguably not what schools are known to excel at providing for their pupils. “At school, you’re sat down, you’re told what to do, what to think, but in the work environment you have to think for yourself. I look back now and I think, that’s where it all started.

“Hospitality gives you so many skills. You had to work under pressure, and it was busy and hectic and you’re talking to a lot of people. It was managed chaos.”

Davis muses that nowadays, many young people she knows are only just developing those skills aged around 16 or later. “There’s something missing,” she tells me, “around building up that experience and those skills earlier on.”

With those six years of restaurant experience, Davis then got into Leeds Beckett University to study hospitality and business management, with a plan to get into top roles in the industry.

This takes us into a brief sideline in our conversation in which she strongly criticises the Department for Education’s plans to prevent students who have failed English and maths GCSEs from attending university, as well as threatening to defund what they term as “Mickey Mouse degrees”.

“Who are they to say what those are?” she says bluntly. “If they want to limit access to university to those groups we should probably be encouraging to go, then this is how to do it. It’s completely wrong.”

Anyway- after her degree, the long and anti-social working hours in the hospitality industry seemed unfeasible, and so aged 24 Davis studied a PGCE at Leeds Trinity University in business and economics, specialising in 14-19 education. By complete fluke, one of her two placements was in FE, at Leeds City College.

“I didn’t like the school placement, and if it wasn’t for the experience of the college placement, I probably would have left.” This suggests that in order to recruit more staff to the sector, an obligatory teacher training placement in FE might not be a bad starting point for the DfE.

From then on Davis rapidly climbed the ladder, taking on big workloads and responsibilities as she went: first a lecturer in business and economics at Calderdale College in Halifax from 2002 until 2005, then head of department for business and enterprise at Park Lane College (now a campus with Leeds City College) until 2010, then another head of department role at Kirklees College until 2015, then vice principal at York College until 2019, before she joined Leeds College of Building.

En route, Davis met three important women. The first was Joyce Wilson, her mentor as a newly qualified teacher at Calderdale College.

“Joyce told me that if you want to progress, you need to move and keep moving, because experience in different places is important,” explains Davis. It was advice she clearly took. “She was also very supportive. Your first teaching role is hard, and she was brilliant.”

This more gently supportive approach was different to her next role model, Vicky Slater, her line manager at Park Lane College.

“It was a very different style of management, very straightforward, no nonsense, very black and white,” smiles Davis. “People might have thought she’d be difficult to work for, but she wasn’t. If you worked for her, you really enjoyed it, because she was very clear what the expectations were.”

Having experienced these two differing leadership styles, it was at York College, under then-principal Alison Birkinshaw, that Davis learnt the value of a leader being comfortable with their own style (on her retirement, the York newspaper The Press described Birkinshaw as “exceptional”).

“I learnt so much from Alison about what matters, especially that you do leadership how you want to do it, otherwise it’s not authentic to you.” The attention to detail and depth of experience when making decisions was amazing, says Davis.

You have to do leadership how you want to do it, otherwise it’s not authentic

Birkinshaw would email around, for instance, having spotted the only student out of hundreds off timetable. “You’d think, how did she see that?” Davis laughs. “It was an incredible level of detail. It was all about doing what was right for the college and the learners.”

Having been surrounded by challenging and high-quality environments – from her restaurant right through the FE sector – Davis has made it to the top in two decades. What are the challenges ahead?

The first, of course, is staffing. The college currently has 15 lecturing vacancies out of 200 lecturing staff, and it’s not helped by a booming construction industry trying to recruit for big national infrastructure projects, such as HS2.

“Our ability to compete with the construction industry is impossible, particularly with the cost of living crisis,” says Davis frankly. Because of the shortage of staff, the college is having to pay some staff overtime, or simply not lay on courses. One of her first tasks from September will be “looking at our people strategy in depth”.

The other big focus will be increasing the diversity of entrants to the construction industry, partly by recruiting more female and minority ethnicity learners. To me it seems extraordinary that I’ve still never seen a woman in a hard hat on a building site.

That’s partly why it’s important to recruit more female staff, according to Davis: all of the female lecturers except one are on the “professional” courses, such as civil engineering, with only one female lecturer on a construction craft course, such as carpentry, joinery or plastering.

It’s about considering who you’re sending into schools

Meanwhile the college also wants to keep reducing its gender pay gap, which was 18.7 per cent in 2021. Across the sector, the college gender pay gap was 10.5 per cent in 2018/19, according to the ETF.

To tackle these inequalities, the college needs to do more to “challenge some of the norms of the industry,” says Davis. She wants employers to get much more involved in meeting school students, putting forward female and minority ethnic speakers as much as possible.

“It’s about considering who you’re sending in when you’re promoting the sector, and not reinforcing stereotypes.”

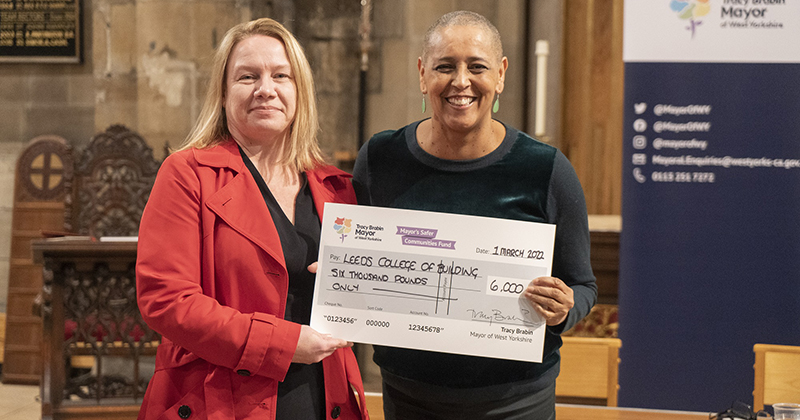

It means that appointing its first female principal, when current chief executive Derek Whitehead steps down, is a particularly important move for Leeds College of Building.

If Davis can lead the charge into schools, perhaps more young women will enter construction – and FE leadership thereafter – in the future.

Your thoughts