The early years sector is facing debilitating staff shortages. Jessica Hill speaks to sector leaders about how reforms to training could help, or hinder, flagship childcare reforms

Qualification reforms intended to train more early years workers could spell a “dumbing down” of the profession and will still leave the sector drastically short of the number needed to deliver the government’s landmark childcare plans.

A vital element was missing when the chancellor announced plans for a childcare “revolution” in March. With 30 hours of “free childcare” proposed for working parents of every nursery-age child, there were nothing like enough early years staff to implement the plans.

The entitlement will be introduced in stages: 15 hours from next April for two-year-olds and from nine months upwards from next September; then 30 hours for all under-fives from September 2024.

The investment represents over £8 billion a year by 2027-28. But it comes at a time when workforce recruitment and retention in the early years sector “appears to have reached a tipping point”, according to the Local Government Association.

Fewer than one in five nursery managers surveyed by the Early Education and Childcare Coalition said they could offer the extended “free hours” entitlement because of the recruitment crisis, with more than half of nursery staff considering quitting in the next year.

The early years sector is understood not to have been consulted ahead of the announcement.

To widen the recruitment pool in which childcare providers can fish, the Department for Education (DfE) is watering down early years qualification requirements and tweaking apprenticeship standards. But there are concerns these measures will reverse the substantial progress on the quality of provision made in the past 30 years.

Will ‘revolution’ need a revision?

Recruitment and retention is a problem across the public sector but it has been particularly devastating for early years settings. DfE data for 2022 shows 334,000 early years workers, down 10,000 (3 per cent) from the peak in 2019. Childminder numbers have fallen by one-fifth since 2019.

In 2019, one in four parents asked by the department said the availability of local 0-4 childcare places was “not enough”; by 2022 it was one in three.

The National Day Nurseries Association (NDNA) said 651 settings closed in 2022-23, up 50 per cent on the previous year.

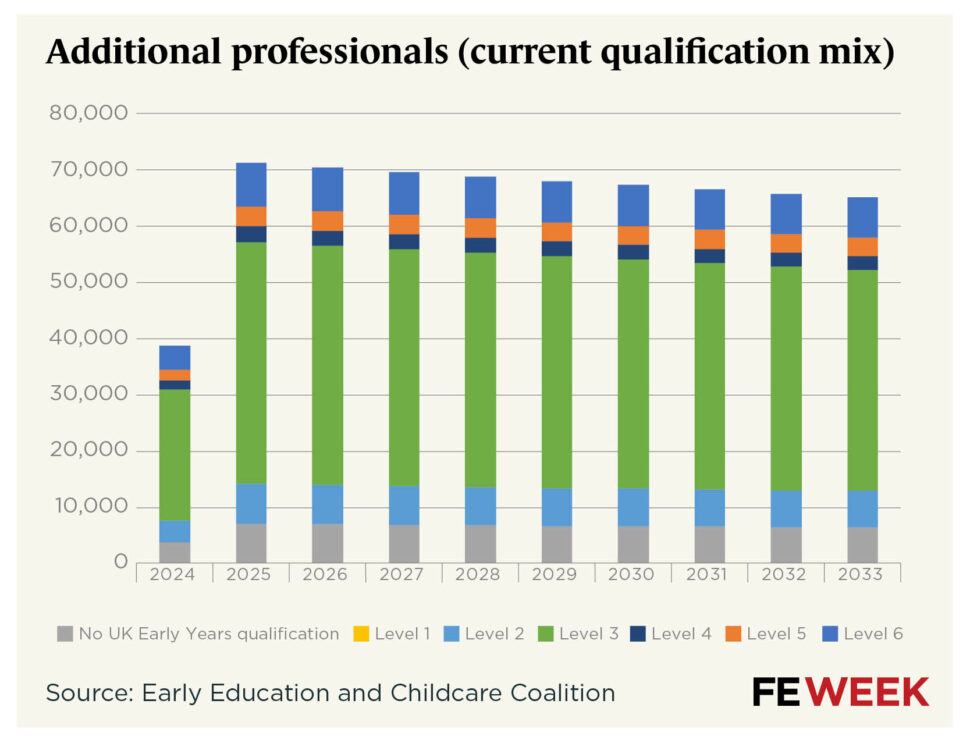

The coalition report found that if all those children aged nine months to two years currently using informal childcare sought to move into formal childcare arrangements in light of the government’s plans, settings would need to boost places by 17 per cent and hire 38,726 more workers next year. A further 71,267 would be needed in 2025, of whom 43,042 would require level 3 qualifications.

The DfE promised a national recruitment campaign earlier this year, but this has been postponed until January.

Even before its childcare reforms are introduced, the recruitment crisis (and particularly the challenge of recruiting level 3 qualified staff) is already cited as a cause of a decline in the quality of staff. This comes as young children are showing increasing signs of complex needs and developmental delays, which require greater expertise.

Neil Leitch, chief executive of the Early Years Alliance, warns that there is “a real risk that [the government’s plans] will result in a de-professionalisation of the workforce at a time when the need for quality care and education is as high as it has ever been”.

No need for maths

The prime minister recently described maths as being “every bit as essential as reading”. But, with more students failing GCSE maths this year (39 per cent, compared with 35 per cent in 2022), his government has been forced to row back on GCSE maths requirements for early years staff.

It recently pledged to remove the need for level 3 early years staff (excluding managers) to have level 2 maths to count in staffing ratios.

Most (67 per cent) respondents to a recent consultation on reform of the early-years foundation stage statutory framework supported removing the maths requirement, which the government said “may have discouraged some practitioners from completing their level 3 childcare qualification”.

The move was also welcomed by awarding body NCFE, which provides around 80 per cent of the qualifications. Julie Hyde, its director of external and regulatory affairs, described it as “hugely significant” as it would enable “many early years practitioners… previously unable to practise at level 3” to be “recognised in their rightful roles”.

There are also calls for the government to go further. Hyde said the maths requirement should also be “removed from the apprenticeship rules, as it has already been with the T Level and other vocational full and relevant qualifications”.

The Local Government Association is calling for the requirement for English GCSE to be dropped too, with some local authority leads suggesting that “not enough focus is placed on empathy or skills in working with children”, according to a paper to its board.

But not everyone agrees with the direction of travel. Dr Iram Siraj, professor of child development and education at the University of Oxford and a judge of the 2024 Khalifa International Award for Early Learning, described scrapping maths requirements as a “dumbing down” of entry into the early years sector.

“It is a really complex situation where all the government is caring about is shoving people into nurseries to do childcare when early education has been a huge part of the drive since the late 90s,” she said. “And we’ve been winning on that – this is a backward step.”

T Level troubles

From 2024, nine early years qualifications will be defunded because they overlap with T Levels.

On the face of it, the T Level in education and early years introduced in 2020 has been relatively successful. But Siraj warns there is still “poor understanding” in the sector as to what T Levels are and “what it means for the salaries and future” of those learners.

Nevertheless, T Levels are slowly gaining traction. The number of students taking the early years qualification more than doubled from 462 in 2021-22 to 989 in 2022-23. More students achieved a distinction or above (34.5 per cent) than in any other T Level subject.

In Ofsted’s thematic review of T Levels this summer, “many providers” said the education and early years course had “significant similarities” to previously offered qualifications. It also praised providers for their creation and use of how providers had created early years classrooms and even sensory rooms.

Hartlepool College targeted 12 learners when it rolled out the T Level in September 2023 and got 14. Its chief executive, Darren Hankey, said finding work placements – which has proven problematic with other T Level courses such as construction – had been “not too much of a barrier”.

But others are less impressed with the qualification. Cheryl Hadland, founder and chair of Tops Day Nurseries, a group of 33 nurseries along the south coast, believes that selling T Levels to young people who want to work in nurseries is an “unforgivable thing” to do. She pulled out of the DfE’s consultation over the T Level because she felt it was “not fit for purpose”.

Hers is one of five nursery chains on this year’s top 100 national employers of apprentices. She objects to how the two-year T Level qualifies students to run a nursery room, whereas her apprentices require “probably three and a half years’ worth of study and practice” before they can do the same.

She said nurseries in the south-west now “don’t have enough apprentices”. This is “probably” because learners are taking T Level courses. Her message to colleges offering the qualification is: “please don’t, you’re taking our intake”.

To T Level graduates applying for supervising jobs, her message is also clear: “Sorry, sweetheart, but you are not anywhere like ready. You can be, and we would love to support you, but […] you’ve used all your funding doing T Levels, so we can’t put you on an apprenticeship.”

Experience-based route

As a result of recent qualification reforms and a proliferation of online courses, there is now some ambiguity around what qualifications are actually required to work in the sector.

Concern around a “lack of clarity” was raised by the LGA, which decried the fact that “numerous training providers” make it “difficult to navigate who is offering high-quality training and who is not”.

But things could get even more complicated because the DfE has just pledged to introduce an “experience-based route”. This would mean that those, for example, in the care sector could have their similar level 3 qualifications count as a childcare qualification.

Three-quarters of consultation respondents agreed with the proposal, with some expressing “frustration” that, without a formal qualification, some “highly competent and experienced” staff members cannot be counted towards statutory staffing ratios.

The department is also allowing students on long-term placements and apprentices to be counted in ratios at the level below their level of study, allowing trainees to “build more valuable experience so they can flourish in their early years career”.

For example, a level 3 apprentice judged by their manager to be performing well could count within the level 2 staff/child ratios.

However, the DfE acknowledged there were “concerns raised around ensuring quality” as a result.

Leitch said that the question of “which qualifications are considered ‘full and relevant’ by the DfE” – and will allow a member of staff to count in ratios – has “long been a cause of confusion for many in the early years sector”.

He added: “All too often, we hear of educators spending time and money on courses and training, only to discover further down the line that the qualifications … hold little, if any, value in real terms.”

Apprenticeship reforms

The DfE also hopes in the longer term to remove barriers to entering the sector by introducing new “accelerated” apprenticeship and degree apprenticeship routes, so that “everyone from junior staff to senior leaders can easily move into a career in the sector”.

Changes are also afoot in the assessment of the early years educator apprenticeship.

The proposed end point assessment changes to the standard by the Institute for Apprenticeships and Technical Education (IfATE) are prompting concerns from NCFE, as they would require face-to-face external assessment.

At a time when the recruitment crisis means assessors are in short supply (or already overloaded), there are concerns that this would further strain the system by causing delays to apprenticeship completions.

Siraj objects to more “on-the-job assessment” because it can be “a way of just getting people through qualifications, rather than ensuring that they had a more rigorous understanding of both child development and practice”.

Funding calls

More than anything, the early years sector says it needs more funding to attract the staff it needs.

The government is boosting childcare funding rates this year and next, for which it is providing an extra £492 million. But the Institute for Fiscal Studies said the uplift fails to address previous years of underfunding.

Siraj believes the reason early years staff are leaving in droves comes down to more than just money, however.

“The sector is exhausted. People prefer not to have the stress of dealing with small children who aren’t toilet-trained and have behaviour issues. They are going to Asda and Tesco because life is just easier.”

We all know what will happen.

The accountants will look at the big long and complicated financial algorithm that is the childcare sector and they will persuade those holding the purse strings that all it requires is a tweak of the ratio of staff to children.

£’s will trump safety concerns until something very bad happens. We live in a time where politics and policy has blended musical chairs with russian roulette.

After being a childminder for 21 years with a level 3 qualification from 2008 , I am finding myself working in a nursery setting as a unqualified nursery assistant. My qualification is now considered not relevant. I stopped working as a childminder in September 21 and started in my nursery job in July 22.

Don’t understand how is this possible , but true it is.