Jo James started as a typist at her chamber and has shot up the ranks to chief executive. She tells Jess Staufenberg why local skills improvement plans can’t be all things to all people

Apparently Jo James has been out dancing all night. She beams and chuckles throughout our conversation, but is seemingly feeling the effects of the evening before on her feet – it was the business awards ceremony at the Kent Invicta chamber of commerce, where she has been chief executive since 2008. (The ‘invicta’ bit means ‘undefeated’ and is Kent’s motto – something to do with scaring off William the Conqueror.)

The names of the winners have been sat sealed inside envelopes for 20 months, because James refused to do a virtual ceremony – which, let’s be honest, is never as good as the real thing.

“We haven’t had a lot to celebrate until last night, even pre-pandemic – it wasn’t a great environment already for business,” she confesses. This is a reference to Brexit, whose effects on local economies have been worsened by the double whammy of the pandemic.

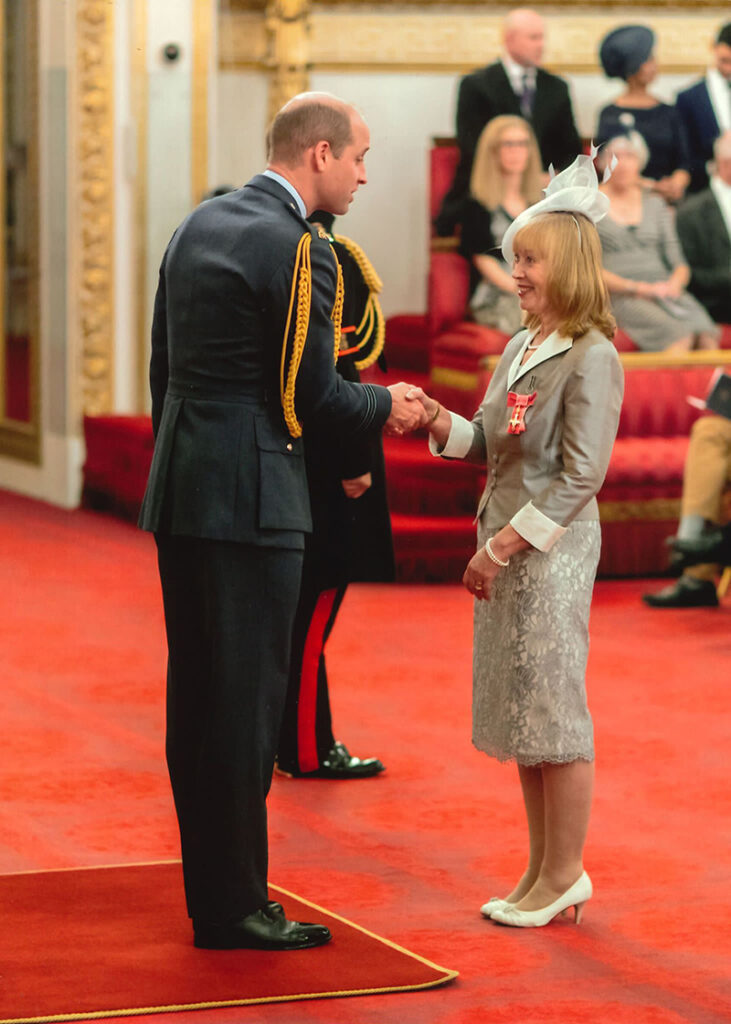

When she won her OBE for services to the economy in 2019, Prince William had apparently asked James how Brexit was affecting Kent. She’d joked that the trip to Buckingham Palace had at least “given her a day off from Brexit talk”, which, according to Kent Online, made him laugh.

But even someone with a cheeky sense of humour like James (she got her dog on the same day she received her letter from Buckingham Palace, so he’s called, you’ve guessed it, Obe) does not try to make light of the situation facing employers now.

After Brexit came Covid, plus a prime minister whose flustered address this week to the Confederation of British Industry was criticised as a “failed speech” and “inappropriate” by some business groups.

“To thrive, business needs stability and clarity, and clarity is probably more important,” continues James. “If you don’t have clarity, how can you plan? We’ve had a tough four years of uncertainty. Businesses need to know what the ground rules are.”

This perhaps explains why James is so frank about where her loyalties lie, and how she sees the role of the government’s local skills improvement plans (LSIPs). Her chamber was one of eight to successfully bid to pilot an LSIP, and she provides fascinating insights on the process behind it. But to start us off, she is clear with me what the LSIP is for.

“I need to inform and keep all stakeholders on board, but the only voice I need to hear right now is the voice of employers. Yes, there are young people not in education, training or employment (NEET), and there’s the 16-19 agenda, but I’m not being dragged into that. For this piece of work, it’s about the voice of employers.”

The other stakeholders are universities, FE providers, the Careers & Enterprise Company, local authorities, private providers, and more, says James. But she argues she must prioritise employers, because they desperately need to be heard.

“What skills we’re getting in the county at the moment is driven by the student, and there’s no relation between what a student wants, and what business wants, and the growth areas we’re going to have,” she explains. “And actually there’s a mismatch between what’s coming out of HE and FE, and business. That’s not fault of colleges: that’s a fault of the system.”

The skills we’re getting at the moment is driven by the student, not business

One of the systemic problems is the way FE is funded, continues James. “Colleges of course need to have sufficient people to make a course financially viable […] so one of the things the government can do is to enable colleges to put on not so popular courses that are really essential to the growth of the county.”

But how many young people – particularly in Kent, with London so close – will then stay in their county? I ask. How will the chamber ensure students who have taken critically important college courses don’t leave, and the government hasn’t wasted money on a course with no tangible local benefit?

James nods. “Yes, it’s the big London agency that has the pull.” The pandemic has put rural economies even more on the back foot in this respect, she continues.

“On the one hand the pandemic has given us opportunities, but on the other hand there’s also a threat.” Previously, explains James, Kent’s employers could compete with their counterparts in big cities by pointing out the drawbacks of the length and cost of commute. With more people working from home, that’s no longer the case.

“So that’s driving up salary costs here, because employers are having to compete to make the offer more compelling.” It’s a “much more candidate-driven market,” James adds.

Placed in this context, with business struggling on all sides, James’s friendly but firm determination to listen to them foremost makes more sense.

“I’m not getting sidetracked. The local authority may have a real problem with NEET and want to come and talk to me about it, but that’s for a later stage, that’s not now. The whole thing is about ensuring we’ve got the employer voice at the heart of FE.”

There do seem to be a few tensions here, which will need someone as friendly and light-touch as James to steer through. She’s got a clear process for trying to bring all voices to the table – but business gets the final look-in.

To begin with, her team is gathering the ‘data’ on the problems facing employers. It’s a three-pronged approach: first, through direct conversations and surveys with 25 member organisations such as the Federation of Small Businesses, the Institute of Directors, the National Farmers’ Union, the House Builders Association and so on, asking them and their members for their views.

The second approach is through a market research company gathering responses from at least 2,000 businesses, asking about recruitment, in which sectors and which skills, and so on. The third is focus groups, with 20 to 30 people led by James and her team.

James expects three issues to become clearer: “the immediate skills needs; the technical qualifications and what needs to change there; and where there is a lack of people going into key sectors”. She is already aware that the sectors most struggling in Kent are manufacturing, engineering and agriculture.

This information will then be gathered and put to an “employer board”, which James expects to convene in the next two to three weeks with about 30 employers (she is clear she doesn’t just want the “usual suspects” representing local business, but those who don’t often speak up too).

“We’ll then say to the board, this is what the data is telling us – does this problem resonate with you? And if the answer is yes, we move on to creating a solutions panel.”

The solutions panel is where FE providers come in ̶ along with HE and private training providers, government department representatives, local authorities, as well as employers and businesses. The panel will propose recommendations to tackle the problems identified by businesses, says James.

“Then we’ll take those solutions back to the employer board and say, do these sound the right solutions to you?”

It’s clear who the LSIP is serving – business – but then, that’s what the government has contracted James to do, and she makes a fair point about the mismatch between skills gaps and education. The only problem is convincing everybody else the LSIP is definitely their LSIP too.

“That’s why it’s so key that those stakeholders are brought into the process, so actually it’s not a chamber of ‘Jo James’ LSIP ̶ it’s a Kent and Medway LSIP,” says James.

But with colleges facing possibly legally binding LSIPs, it will be important that providers aren’t made to feel they’ve lost all autonomy over what is in the best interests of students.

James, however, praises how her local colleges for cultivating a close relationship with the chamber, and it is unlikely many college principals will not see the advantages of making LSIPs work.

My final question is practical. Even if everyone is signed up in principle, frustrations could arise if the plan is not smoothly managed. What is the strategy to ensure LSIPs are actually carried out? Who will keep the plan on track?

“To me the LSIP is just the start of the journey,” explains James. “If it’s just one piece of work, it’s a wasted effort.”

If the LSIP is just one piece of work, it’s a wasted effort

James has a major advantage: she is immensely likeable. She is a former FE student herself, having not enjoyed school and taken a secretarial course at Ashford College. She never even intended to lead the chamber, having been interested in hairdressing.

Instead, as a stay-at-home mum, she one day applied to a newspaper advert for “typist, 12 hours a week”, and it turned out to be at the chamber of commerce. Since then she has shot up through the ranks, and was asked to take over as CEO 12 years ago. “I have a wild imagination, and I never in my wildest imagination would have thought I’d be doing this!”

Her team has got until end of February to submit the LSIP. With so much effort put into them by exhausted employers, let’s hope they might work.

Interested in how the skills needs of the public sector (health and social care, public services, education etc) are going to be reflected in LSIPs. How are Chambers capturing this in trailblazer areas?