Schools, colleges and students are eagerly awaiting A-level results on Thursday – the second series of summer exams since the pandemic.

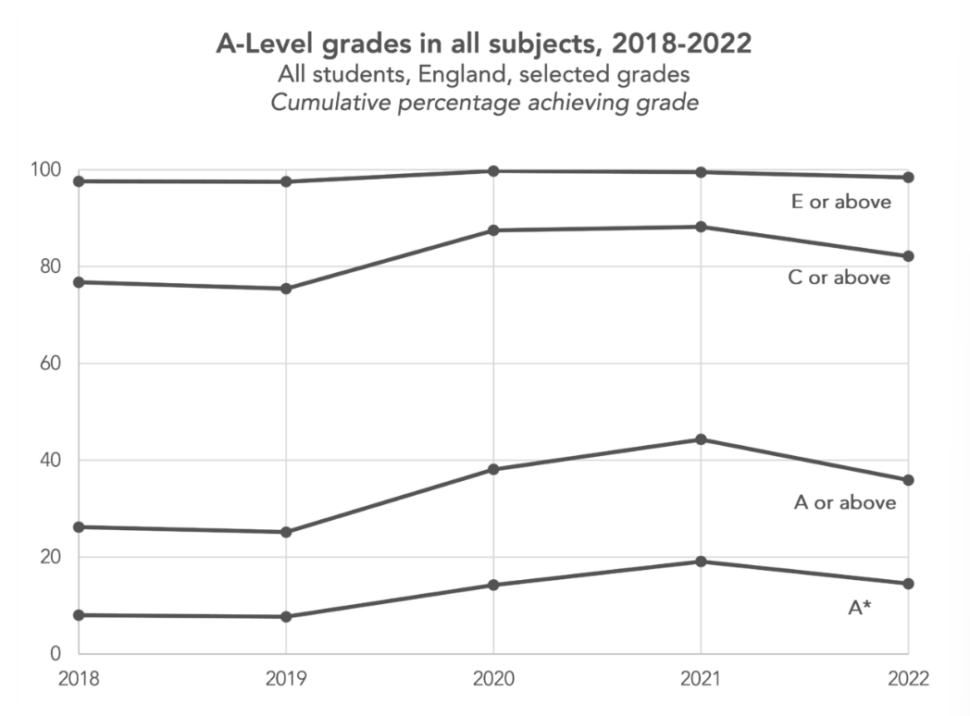

The government and Ofqual have been clear since last year that grades issued will be much closer to pre-pandemic levels.

But as results days near, concerns are emerging about the impact of such a plunge in results on students.

So here’s our explainer on what you need to know about this year’s results …

1. 2023 cohort will bear brunt of grade deflation …

The rolling back of the grade inflation did start last year. Ofqual promised 2022’s results would be a “midway” point between the pandemic highs and the pre-pandemic norms.

However, as FE Week’s sister title Schools Week revealed at the time, there was just a 30 per cent drop in top GCSE grades issued last year, a way off the 50 per cent fall that would have constituted the “midway” point.

While last year’s top A-level grades did fall further, analysis by Education Datalab showed almost all subjects were above this midpoint.

It means this year’s cohort has been left facing the biggest whack in grade deflation.

2. … as ‘50k students set to miss out on top grades’

While grades will fall this year, there are still what have been called “soft-landing” protections in place.

Essentially, senior examiners will make allowances to ensure that national performance in subjects is not lower than before the pandemic.

For example: a student who would have achieved a B in A-level geography before the pandemic will be just as likely to achieve this, even if their exam performance is a little weaker.

This is important because we know, for instance, that students’ maths results have worsened since the pandemic. Were there no protections in place, it’s likely results would fall below pre-pandemic standards.

Exam aids such as formulae and equation sheets were also allowed in some subjects, as recognition that this year’s cohort have also had their schooling disrupted by the pandemic.

But the University of Buckingham predicts nearly 100,000 fewer A and A*s will be dished out, with up to 50,000 students missing out on top grades that they would likely have achieved last summer.

3. And it could be poorer pupils worst hit

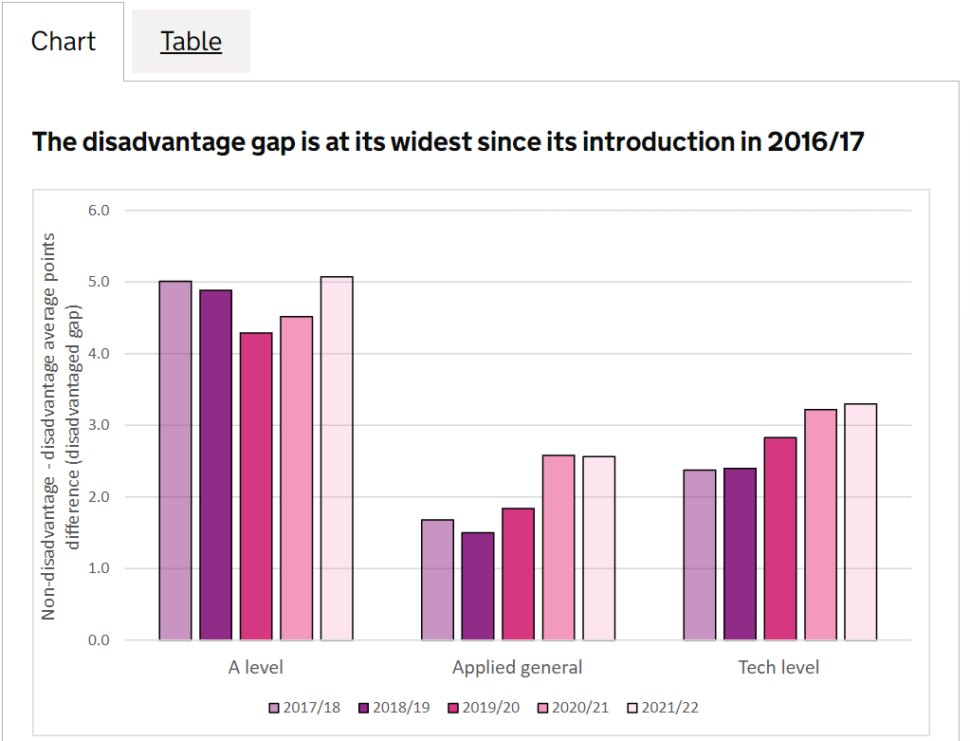

The widest disadvantage gap at A-level since records began was recorded last year. This gap actually narrowed slightly during the pandemic – suggesting that poorer pupils saw their grades rise the most during the teacher grade process.

But as that inflation is wound back, it’s likely those pupils will now be the worst hit.

Michelle Meadows, former deputy Ofqual chief and now education assessment professor at the University of Oxford, warned the disadvantage gap will be larger than before the pandemic which is a “serious concern”.

But she said it can’t be “remedied by any approach to grading – schools and colleges need the right level of resourcing to provide targeted support to those students who most need it”.

A survey of students by the Social Mobility Foundation found that those from disadvantaged or low-incoming backgrounds in England were less likely to have received the help they needed to restore the learning lost during the pandemic.

4. Ofqual says standards must go back for fairness

Ofqual has previously said it’s important we get back to normal so grades “set young people up for college, university or employment in the best way possible”.

The Sunday Times reported that 30 per cent of young people dropped out of some university courses over the two years of pandemic grading – citing it as a reason for the return to “normal” grading.

A quote from an unnamed source added it was “not in young people’s interests to have grading arrangements that do not appropriately support their progression”.

However, Clare Marchant, UCAS chief executive, said this morning she was “struggling to understand” where the data came from.

Johnny Rich, a higher education specialist, also added “it’s very early” to state Covid drop-out rates, as data is yet to be published. Some courses prior to covid already had drop-out rates of 30 per cent, he added.

He believed a “lack of funding and miserable study conditions during the pandemic are far more realistic explanations” for dropouts rather than A-level grading being over generous.

5. High predicted grades could cause a problem …

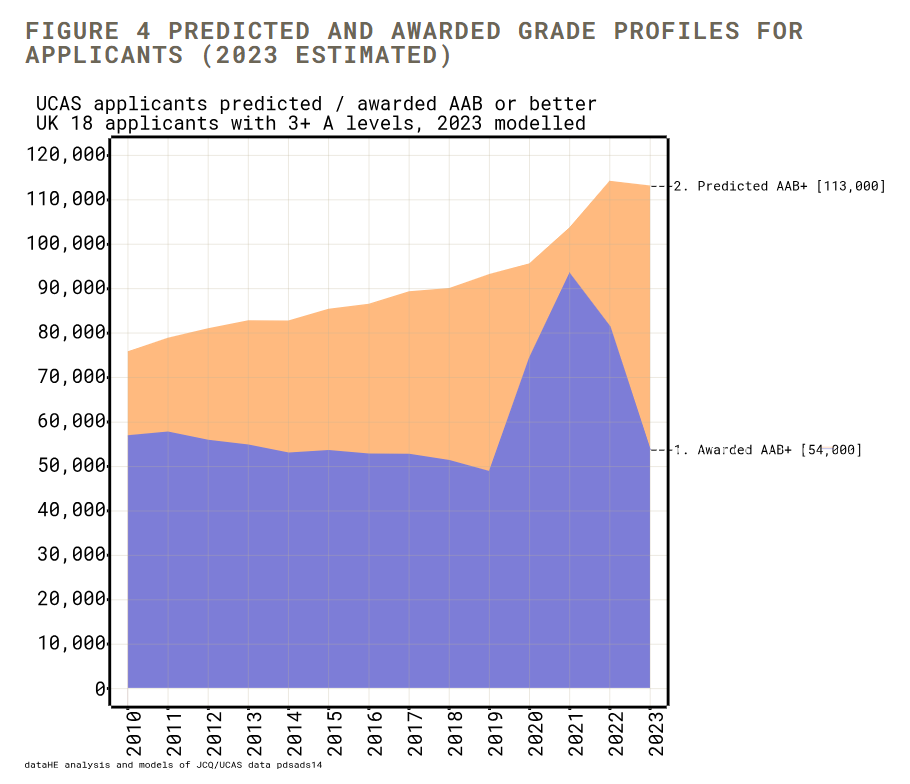

Analysis by consultancy DataHE suggests nearly 60,000 university hopefuls predicted AAB and above could miss these grades on Thursday.

UCAS doesn’t publish predicted grades data until later in the year. But researcher Mark Corver estimated 113,088 students are predicted AAB and above this year by teachers (while awarded grades have “jumped around” over the years, predicated grades from teachers have been “much more stable” so are easier to estimate, he said).

However, his analysis found the actual number of top grades issued could be just 53,718.

“If this happens it will certainly be a big shock for these students, who had the strongest ever GCSE results,” Corver told the Guardian. This year’s A-level cohort would have been awarded higher-than-usual GCSEs during the 2021 teacher grades process.

When asked about the analysis, Ofqual pointed out that only 21 per cent of accepted applicants to university in 2019 achieved or exceeded their predicted grades.

Yet 86 per cent of UK UCAS applicants aged 18 took up a university place.

In September, the regulator recommended that teachers use the familiar pre-pandemic standard as the basis for predicting grades this year. It expected predicted grades this summer to be “much closer” to pre-pandemic years.

6. … but universities say they’ve accounted for it

As Corver points out, grade distribution should not in theory make any difference to getting a university place.

“People are not becoming more or less able; it is just the ruler is being changed,” he said.

However, he did warn “in practice both universities and applicants probably find it hard to completely shake off the grade equivalent of the ‘money illusion’, where you focus on the nominal value”.

Universities also don’t receive a nationwide grading picture until results day.

The Russell Group, which represents 24 leading UK universities, said during Covid there had been “uncertainty around grade boundaries” so universities were “more cautious with offer making”.

But this year, the organisation said it can model offer-making with greater certainty and factored in predicted grades being higher.

Even if more students don’t hit their predicted grades and miss their offers, universities can adapt and show “leniency” during the offer route, or go into clearing to find students.

Asked about the predicted grades gap, Marchant said she wasn’t “particularly concerned” as offers are made in context.

But she said there is a “broader issue” with predicted grades, adding: “We need to keep an eye on it. It’s very easy I think to overpredict but we need to be giving data to schools and colleges to get as accurate as possible around that.”

Another potential issue is that grades in both Wales and Northern Ireland will not return to pre-pandemic standards until next year, meaning results will be higher than for English students. Scotland also took a “sensitive approach” to grading.

The Russell Group said admission teams are used to accounting for variation in outcomes annually.

7. Clearing warning: Be ‘quick off mark’ and have Plan B

However, Marchant warned last week that students need to be “quick off the mark” on results day if they want to study at a top university, as competition in clearing will be tougher this summer.

Analysis by the PA news agency found fewer courses available in clearing this year among the Russell Group universities.

But Marchant said this was down to more 18-year-olds and international students competing for places, not an issue with grades.

The number of UK 18-year-old university applicants was down two per cent this year compared to last year, but still above 2021 figures by 2.8 per cent.

However, the offer rate for this group is higher at 76.2 per cent, compared to 73.9 per cent last year.

Marchant added they expected the vast majority of students will receive their first choice on Thursday.

But she advised students to research their options and prepare for a plan B.

The grades were returned to the 2019 pre covid levels and then some ♀️These kids were predicted A* and A were dropped down to B And C . That’s a two grade drop as a parent watching your child feel as though their dream they had been studying every day for ripped away is heartbreaking . The goverment certainly didn’t factor the emotional impact into the figures did they

This has been especially damaging to kids from here applying in Ireland. They boosted 71% of grades by an average on 8.9% and the conversion rate to CAO points was set in 2019.